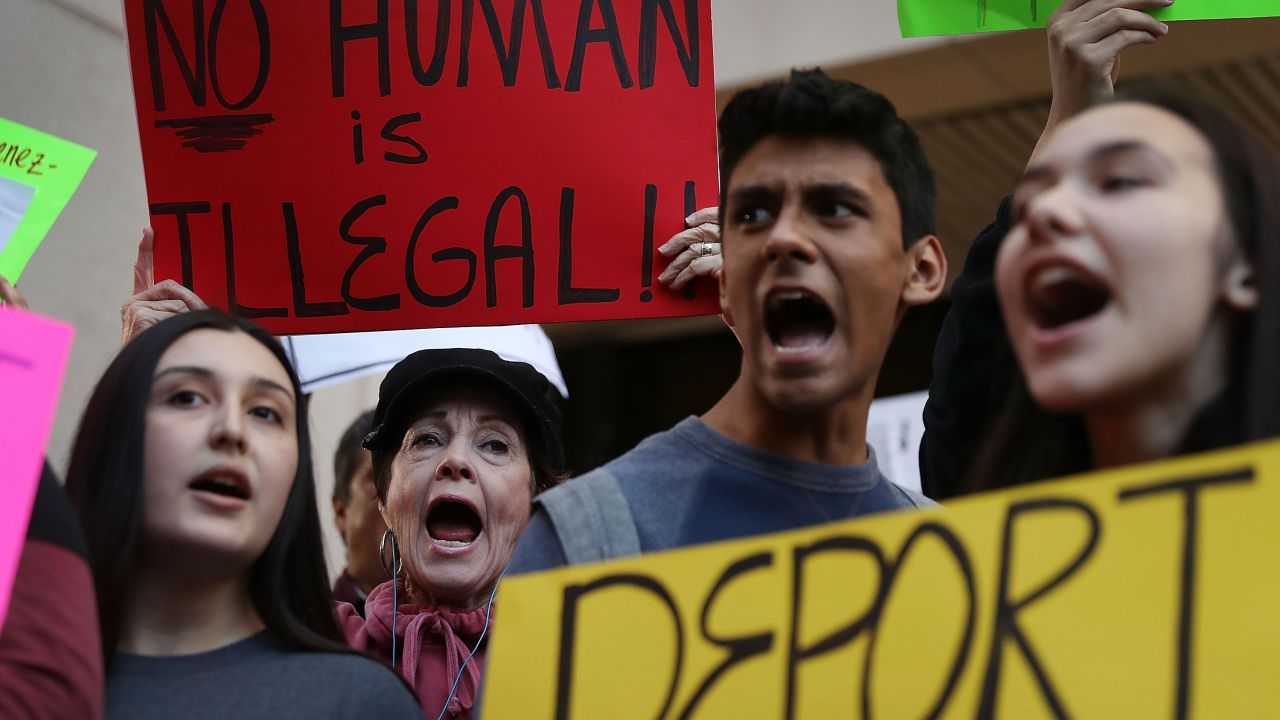

Protesters gather against Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Gimenez's decision to abide by President Trump's order to effectively abandon the county's stance as a "sanctuary" for undocumented immigrants, outside the Stephen P. Clark Center Government Center on Jan. 31, 2017. Miami-Dade County had stopped holding potentially illegal inmates in 2013, but the mayor's decision overturns that practice to comply with the president's executive order. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

On Tuesday, US District Judge William Orrick III, ruled that the Trump administration’s threat to punish so-called “sanctuary cities” is unconstitutional. The judge issued a temporary injunction prohibiting the Justice Department from trying to withhold federal funds from San Francisco and Santa Clara, California. President Trump tweeted that he will fight the ruling all the way to the Supreme Court.

What is a sanctuary city?

Short answer: There is no legal definition for a “sanctuary city.” In fact, sanctuary jurisdictions are often not cities at all, but counties. Most share, to varying degrees, policies that push back against federal requests or changes in law that require local law enforcement agencies to do the federal government’s job of enforcing immigration law. This may include not using local resources to detain immigrants, or having a department policy not to inquire about immigration status.

Sanc·tu·ar·y

The term “sanctuary” does not refer to a uniform policy, nor does it have any legal bearing. Lena Graber, a staff attorney for the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC) says it is more of a “brand” or a blanket term that labels jurisdictions that don’t fully cooperate with federal immigration officials. When people cite the number of sanctuary cities across the country they are often referring to jurisdictions that have a policy against immigration detainers (see below). The ILRC has counted about 600 counties that don’t support these detainers, but that is just one piece of the puzzle, says Graber.

Trump’s Executive Order

Despite having no definition of sanctuary, five days after taking office President Trump signed an executive order that threatened to punish sanctuary jurisdictions by withholding money if they refuse to comply with federal law 8 U.S.C. 1373. That law is actually very narrow, explains Graber; it says “that a locality is prohibited from enacting a policy that limits communication of their officials with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) about someone’s immigration status.”

In other words, it is a law against preventing communication and has nothing to do with whether your officials help ICE or not; whether you voluntarily detain people or not; or whether you call yourself a sanctuary city or not. Even places that recognize themselves as sanctuary jurisdictions do not violate this law by telling people they can’t communicate with ICE. They also do not prevent ICE from doing its job to enforce federal law.

It is perfectly legal, however, to choose not to do ICE’s job. It is also completely legal to have policies telling local public officials, law enforcement or administrators not to ask individuals about their immigration status in the course of basic operations.

ICE Detainers

The administration, in its actions and threats, suggests that sanctuary jurisdictions are those that don’t comply when ICE asks local law enforcement to detain people. But plenty of nonsanctuary jurisdictions also won’t uphold ICE detainers because they are not official warrants. Detainers are not even orders — they are requests sent by ICE to local law enforcement asking them to hold individuals suspected of being undocumented for 48 hours until they get there to begin deportation proceedings.

Detainers are especially controversial because the ongoing detention is really a new arrest without legal justification. As Graber explains, “The officers are saying, ‘We would have released these people, but instead we are going to keep detaining them to wait for ICE to come to get them.’ They should be free to go home but they are in continued detention instead.” Many local authorities, whether they declare themselves sanctuary jurisdictions or not, will honor a detainer for a violent criminal. But if the individual doesn’t pose a danger to public safety, they will not hold him or her out of concern for the Fourth Amendment.

The Fourth Amendment protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures of property by the government, as well as from arbitrary arrests. Detention “needs to be based on probable cause,” says Graber, “Or it needs to be on the basis of a valid warrant reviewed by a judge. ICE detainers are not necessarily based on probable cause, and they are never reviewed by a judge.” Multiple federal courts have confirmed that local jurisdictions are not required to honor detainers and may be legally liable for violating civil rights if they do.

Federalism and ICE

The 10th Amendment maintains a separation of powers between national and state governments that reserves rights to the states. Under the 10th Amendment, the federal government can’t make state or local governments use their resources, like police officers and jails, to enforce federal law. In legal terms, it cannot “commandeer” state and local resources to enforce federal immigration laws.

As we noted in Federalism, Explained: It was federalism that struck down the Medicaid expansion provision in the Affordable Care Act. In 2012 the Supreme Court ruled it’s unconstitutional to make all federal Medicaid funds to states conditional on compliance with the federal law. This same “anti-commandeering” doctrine will be used again if the Trump administration follows through on its threat to withhold federal money from sanctuary cities.

Community Policing

Attorney General Sessions has threatened to withhold community policing grants from sanctuary cities. Many city and county police department adopt what they call a “community policing” strategy that does not enforce federal immigration laws. Local law enforcement wants to maintain the trust of everyone in its community. “We don’t care about your immigration status. If you are the victim of a crime, you need to report it,” says Chief Tom Manger of the Montgomery County Police Department in Maryland. “I don’t care who the president is, the federal government cannot tell us how we are going to do our job at the local level.”

Still, Chief Manger says Montgomery County is not a sanctuary jurisdiction. “If we arrest someone for a serious crime — a gang member who is committing armed robberies — and we fingerprint him and the prints go to FBI or DHS, and ICE comes back and asks us, ‘Is he in your jail, and when is he getting out?’ we tell them and ICE will be at the jail to take custody.” But Manger says they will not ask people about their immigration status. “We don’t care,” he says. “What we care about is whether they were the victim of a crime, and whether we can get them the help they need. We need them to trust us, to report crime and to work with us.”

Withholding Federal Funds

President Trump’s executive order threatens to take away funding from cities that violate 8 U.S.C. 1373, the federal law that protects communication between local governments and ICE. This law is not actually about ICE detainers. But Trump’s executive order also says the Justice Department can designate any state or local government a sanctuary jurisdiction in order to punish it. Already six jurisdictions have filed lawsuits charging that President Trump has overstepped his authority — San Francisco was the first, followed by Santa Clara County, California; Chelsea and Lawrence, Massachusets; Richmond, California and Seattle. The basis of all the suits is that the executive order cannot coerce local governments into using their resources to do federal work.

On Tuesday, in response to the suit brought by San Francisco and Santa Clara County, a California judge issued a nationwide injunction saying Trump can’t withhold federal dollars from so-called sanctuary cities. Federal judge William Orrick ruled, “The Constitution vests the spending powers in Congress, not the President, so the Order cannot constitutionally place new conditions on federal funds.” His ruling also determined that the order violated the constitutional principles of federalism and due process—without a clear definition of “sanctuary jurisdictions,” there’s no way to avoid punishment.

Welcoming Cities

There is a growing list of communities that label themselves “welcoming.” This is an established network of more than 160 cities and counties guided by the principles put forward by Welcoming America a nonprofit organization begun in 2009. This network includes municipal government, business, faith-based groups and nonprofit outreach organizations that follow principles of inclusion and build communities where immigrants and refugees feel welcome and supported. As the word “sanctuary” becomes more and more controversial, says the ILRC’s Graber, “Many places that want to be somewhat welcoming to immigrants take on the “welcoming” brand, and places that are a little bit more aggressive or anti-Trump embrace the “sanctuary” brand. But they are part of the same spectrum.”

History

The term “sanctuary” in modern times came out of the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s. During that time, a network of religious congregations banned together to provide legal and humanitarian assistance to thousands of Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees who came to the United States seeking asylum from violent civil wars, but were turned down. Hundreds of Christian and Jewish congregations took up the cause and assisted refugees in defiance of the law. They provided lawyers, food, medical care and employment. These congregations cited Nuremberg principles of personal accountability to justify breaking laws against smuggling undocumented immigrants. A number of activists were arrested and brought to trial before Congress passed legislation in 1990 that granted Temporary Protected Status to nationals of certain countries.

Note: This post was updated on April 26.