Dirt streets still make up parts of East Biloxi on Jan. 2, 2016 in Biloxi, Mississippi. According to the US Census Bureau, Mississippi is the nation's poorest state, with a median income of $39,680. The city of Biloxi has struggled to make progress after the devastating flooding from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

When Donald J. Trump assumes the presidency and lays out his agenda for our country, he will likely proclaim himself, as he did in the campaign, the voice of “the forgotten Americans.”

To Trump, these “forgotten Americans” are the white working-class Rust Belt voters who catapulted him to the presidency, people who see themselves as an aggrieved silent majority whose diminished social and economic status never gains the attention of a coastal elite preoccupied with political correctness and minority rights.

But the truth is this: These white working-class voters have never been forgotten, while those who truly are forgotten still don’t have a voice.

If Trump really wants to speak for forgotten Americans, he would travel to the Mississippi Delta and the rural Black Belt of the American South, where conditions are so wretched and dire that even a struggling Rust Belt factory town might seem like a bountiful paradise of opportunity and wealth.

Campaign events tell the real story of who’s forgotten and who isn’t, and the verdict is clear: White working-class voters in the Rust Belt are far from forgotten, but impoverished areas that have no Electoral College value are completely ignored.

According to data compiled by the organizations FairVote and National Popular Vote!, in the four presidential elections since 2004, candidates held 46 percent of their general-election visits in just five Rust Belt states — Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan and Iowa — whereas they held none in Alabama and a grand total of one in Mississippi, and that was a predominantly white rally Donald Trump held in Jackson, miles away from the largely black Delta.

Think of the quintessential white working class community of Brown County, Wisconsin, home to Green Bay, which may not be thriving but where the poverty rate is 11.1 percent and the median household income is $53,527, just about the national median of $53,889.

Now consider Holmes County, Mississippi, where 43.3 percent of residents live in poverty, median household income is a mere $20,732 — and households in one of its nearly all black towns, Tchula, make an unconscionable $13,273 per year.

Or think of Greenwood, Mississippi, where half of all blacks live below the poverty line; or Wilcox County, Alabama, where 50.2 percent of blacks live in poverty compared to 8.8 percent of whites. These numbers are not uncommon throughout the rural South.

Walk through Clarksdale, Mississippi — the epicenter of Delta blues music and home to the legendary juke joint, Red’s Lounge — and most stores are shuttered. One brave restaurant that tried to bring contemporary cuisine there could afford to open its doors only Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights, and then closed down.

Many Delta and Black Belt residents live in dilapidated shacks with no proper sanitation, where sewage drains right into the ground and contaminates both the soil and water. The Greenville, Mississippi, infrastructure was in such disrepair that for years the town spilled raw sewage into creeks, rivers and bayous, according to a 2016 lawsuit brought by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality. The Economist reports that life expectancy in parts of the Delta is lower than it is in Tanzania.

Nor is education a way out for many Black Belt and Delta residents. In Sumter County, Alabama, 38.5 percent of adults with either some college or a two-year degree are living in poverty, meaning that those who try to pull themselves up still can’t catch a break.

And the educational system itself barely deserves the name “educational system.”

A former student who spent two years teaching high school in the Delta wrote to me about one teacher who built a wooden barricade covered in barbed wire around her desk, another who fell asleep in class, another who had students hand-copy chapters of the history book onto their own paper and then tested them on it. The Spanish teacher knew no Spanish, so the class spent its days making Mexican arts and crafts. The copy machine hadn’t worked for weeks, and in the stifling Delta heat the air conditioning system barely functioned.

According to The Washington Post, of the 40 Mississippi school districts to receive a D or F from the state, 24 of them have student bodies that are more than 95 percent African-American.

For many young black men, schools are a path less to opportunity than to incarceration. In 2012 the Department of Justice sued Meridian, Mississippi, for creating, in effect, a school-to-prison pipeline in which Meridian authorities routinely handcuffed, arrested and jailed students without probable cause for what would typically be considered school disciplinary issues, such as refusal to follow the directions of a teacher or simply disrespect. Students on juvenile probation because of these arrests were regularly imprisoned for dress code violations, flatulence in class or using the bathroom without permission. These punishments “shock the conscience,” the lawsuit stated.

Nor are criminal justice abuses confined to schools. In the Delta, because there is only a patchwork public transportation system supplemented by a makeshift arrangement of buses and vans provided by a network of nonprofits, cars are a lifeline for most people trying to work or buy groceries. But driving itself can be a ticket to prison. Travel around the Delta and you’ll hear story after story about black drivers, especially men, who get pulled over and fined for a broken taillight — and then, with no money to fix the car or pay the fine, they get pulled over again and their punishment this time is incarceration.

It’s hard to see hope where there are few jobs, failing schools, ramshackle homes, contaminated communities and a path in life that consigns many to prison rather than prosperity. Unlike their Rust Belt brethren, they never had even a fighting chance at the American Dream.

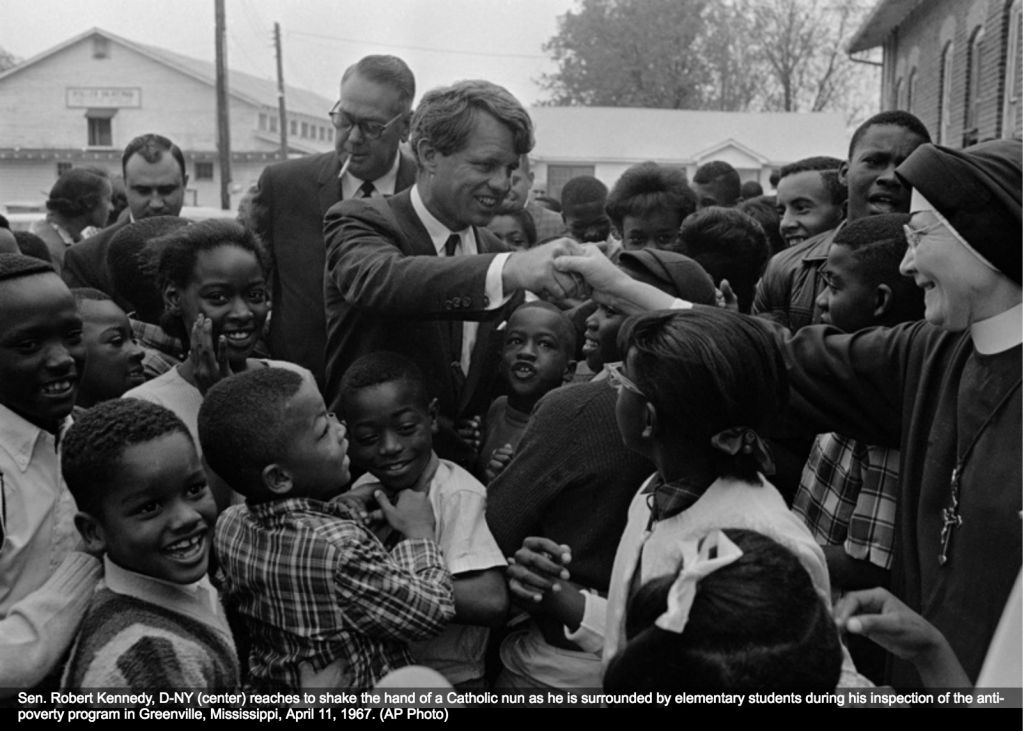

Yet with no political power or say, few national leaders, politicians or intellectuals advocate for them or take on their cause. In 1967 Robert Kennedy visited the Delta, and upon seeing the grueling poverty and hunger, asked plaintively, “How can a country like this allow it?” In 1999 Bill Clinton came to Clarksdale and convened a roundtable of local and national business leaders, pushing for more investment in the region. But that’s about it. These truly are the forgotten Americans.

All of this isn’t to say that the white working class doesn’t have its challenges. Rusted plants, boarded-up stores, hollowed-out downtowns, painkiller addictions — people who felt entitled to an American Dream but now see it slipping away ought to speak up and challenge a status quo that isn’t working for them.

But unlike residents of the Black Belt and the Mississippi Delta, who never seem to matter when elections come around, these white working-class voters have had their say. Candidate after candidate visits them, panders to them and appeals for their votes — feeding them patriotism, promising law and order and flattering them that they are indeed the true hard-working and “real Americans.”

And increasingly, from the Nixon Silent Majority years onward, they have made their voice clear, voting for politicians statewide and nationwide who favor gun rights, oppose unions, fight universal health care, claim tax cuts will create jobs and resist affirmative action, public infrastructure investments and government programs designed to help people get a leg up on life. These white working-class voters have staked out their priorities and exercised their voice — and contrary to the “forgotten American” trope applied to them, they have determined state and national elections.

Perhaps the political lesson is this: When the forgotten Americans are working class, white and from battleground states, they get labeled “forgotten” and everyone pays attention to them. But when the forgotten Americans are poor and black with no electoral clout, they are, simply, forgotten.