WELCH, WV - MAY 19: A coal miner takes a break after his shift at a small mine outside the city of Welch in rural West Virginia on May 19, 2017 in Welch, West Virginia. West Virginia, a state where President Donald Trump won in a landslide by defeating Hillary Clinton 67.9 percent to 26.2 percent, is also one of the nations poorest states where nearly one in five West Virginians struggled to afford basic necessities in 2015. The state was historically dependent on coal mining and manufacturing. While mine employment is up slightly since the election, the state has continued to see a surge in male unemployment and an epidemic of opioid use among its population. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

It’s rarely clear what exactly Donald Trump means when he makes promises.

So when he promised that the “forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer,” perhaps it was wrong to assume that he meant struggling Americans, including the 45 million who live below the poverty line.

At this point, it’s well documented that the poor will in fact bear the brunt of much of what he and his administration hope to accomplish in the next few years. From defunding federal agencies to repealing Obamacare to loosening regulations on polluters and the financial industry, the agenda shared by the White House and Republicans in Congress puts those who are already living on the edge in an even more precarious situation.

This is convenient for the administration, because poor people tend not to be engaged politically. It’s not that they are voting against their own interests — they’re not voting at all.

But activists rallying to oppose Trump’s agenda are trying to change that.

Talking issues, not politics

— Alexandra Gallo

The question of how to amplify the voices of poor Americans was front and center at The People’s Summit, a conference held earlier this month in Chicago and organized by National Nurses United, a union that has emerged as a major force in progressive politics. The summit featured keynote speakers including Bernie Sanders, Van Jones and newly elected Jackson, Mississippi Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, as well as a host of organizers, politicians and activists working on issues ranging from immigration to poverty to climate change.

“Most people are registered to vote but you’ll find that they’re not turning out to vote,” says Alexandra Gallo, an organizer with West Virginia Citizen Action Group who participated in a panel on rural organizing. “They don’t feel that it matters or that it’s going to make a difference, or they don’t want to vote for the lesser of two evils.”

Gallo’s group is currently focused on bringing jobs to coal country and protecting health care for West Virginians. In 2013, the state’s Democratic governor, Earl Ray Tomblin, expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. If Republicans make good on their promise to repeal the law, 173,000 West Virginians covered by the Medicaid expansion could lose their health care. That’s about 9 percent of the state’s population.

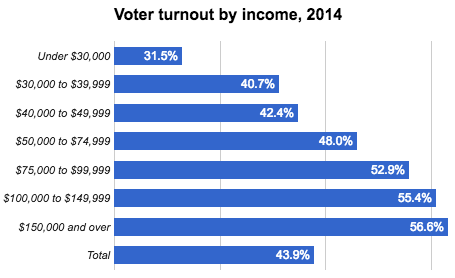

Chart courtesy of Politifact

“We’ve been canvassing around ‘Medicare for All’ and it’s resonating very deeply with folks here,” Gallo tells BillMoyers.com.

After Bernie Sanders made it one of the key issues in his campaign, some of the Democratic Party’s more left-leaning members have endorsed a single-payer health care system. But the party has fallen out of favor with West Virginia’s voters. The state is, increasingly, electing Republicans, and those West Virginians who showed up at the polls voted overwhelmingly for Trump in 2016.

So Gallo avoids talking about politicians and instead talks about specific issues — in this case, the health care that many West Virginians stand to lose if Republican senators manage to repeal Obamacare.

“Oftentimes I’ll lead with ‘there’s no political party, there’s no elected official that’s going to get us out of this mess. We have to be diligent in taking action when it comes to the issues we care about,’” she says. “And we realize that not everyone has the time or capacity to take action. And that’s why giving folks the truth and real information — and following up with these people — is so critical.”

The feedback loop of economic and political inequality

Data collected by the Pew Research Center in 2014 found that only half of the least financially secure Americans are registered to vote, and only one-fifth planned to cast a ballot in that year’s midterm election. These voters also didn’t follow politics very closely — only a quarter knew which party controlled Congress, and only 14 percent had gotten in touch with an elected official in the last two years.

Across the board, Pew found that wealthier Americans were more politically knowledgeable and more engaged. And so, unsurprisingly, in study after study, researchers have found that the policies that make it through Congress and are signed into law tend to favor the wealthy — often at the expense of the poor.

It creates a cycle that reinforces itself. The poorer people are, the harder it is for them to fight back by advocating for policies that will help them. And people who so often have had the political system used against them tend to be suspicious when outsiders show up offering politics-based solutions.

“The issue that I have with people who are not from the community is that they tend to bring their knowledge of the way it was where they’re from, and not understand what it’s like to work and organize in a rural community,” says Catherine Flowers, an organizer in Lowndes County, Alabama, where the median household income is around $26,000. Flowers also attended the People’s Summit this month.

“You don’t just show up and knock on people’s doors,” she continues. “You have to develop trust. They want to know why you’re there. How long you plan to stay. And usually, when people are showing up, they assume that they have some money associated with their being there that probably will never get to the community.”

Flowers started her work in the county in 2001, advocating for rural people who were not connected to municipal sewer systems — which often meant raw sewage leaked into yards where children played, making them sick. She founded the Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise, a group that works on environmental justice issues; she also works with the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit run by New York University law professor Bryan Stevenson that works to help America confront its racist past. Because Flowers grew up in the community, and because she has been working on environmental justice issues there for more than a decade, many in Lowndes County listen when Flowers talks about how climate change will affect rural people — and how government inaction could make it worse.

“We’re starting to have a conversation”

“I think sometimes we talk on such a high level that people don’t understand,” she says. “We have to talk to them in a way that’s relevant to them.”

Flowers elaborated that many in her community grew up close to the land. “I talk about, ‘Have you noticed that there’s a change in the weather? Have you noticed that we’re seeing animals here that we’ve never seen before?’ Most people have noticed some changes. I ask, ‘What have you noticed?’”

People point out that it’s warmer than it used to be, that we don’t have two seasons now, and that trees are blooming sooner than they used to, Flowers says. “I ask, ‘What do you think is causing that? Have you considered…’ — that’s a way to do it. You have to first validate what they already know and then offer some possibilities.”

As climate change advances, it will bring new challenges to Lowndes County and to other poor communities across the US, including parasites and disease. “A lot of frontline communities are being impacted already,” Flowers says. She is hoping to convince the federal government to provide funds to help poor communities brace for climate change.

And, perhaps surprisingly, she is hopeful about the direction America is moving in.

“I’ve met Trump supporters who are good people. All of them aren’t racist,” says Flowers, who is black, and whose activism has sometimes made her a target of white supremacists online. “They voted for him because they thought their interests were not being met. It’s the same thing with people who voted for Bernie Sanders — they felt the status quo Democratic Party was ignoring them.”

She sees the election as an important indicator of dissatisfaction with a political order that has made so many of the people she works with feel powerless. And she finds hope in protest movements, including Standing Rock, which saw Native Americans, environmental activists and military veterans standing up against the government and a corporation for environmental justice.

“We’re starting to have a conversation that we should have had a long time ago, and out of this is going to come something better than what we had before,” Flowers says. “I believe that.”