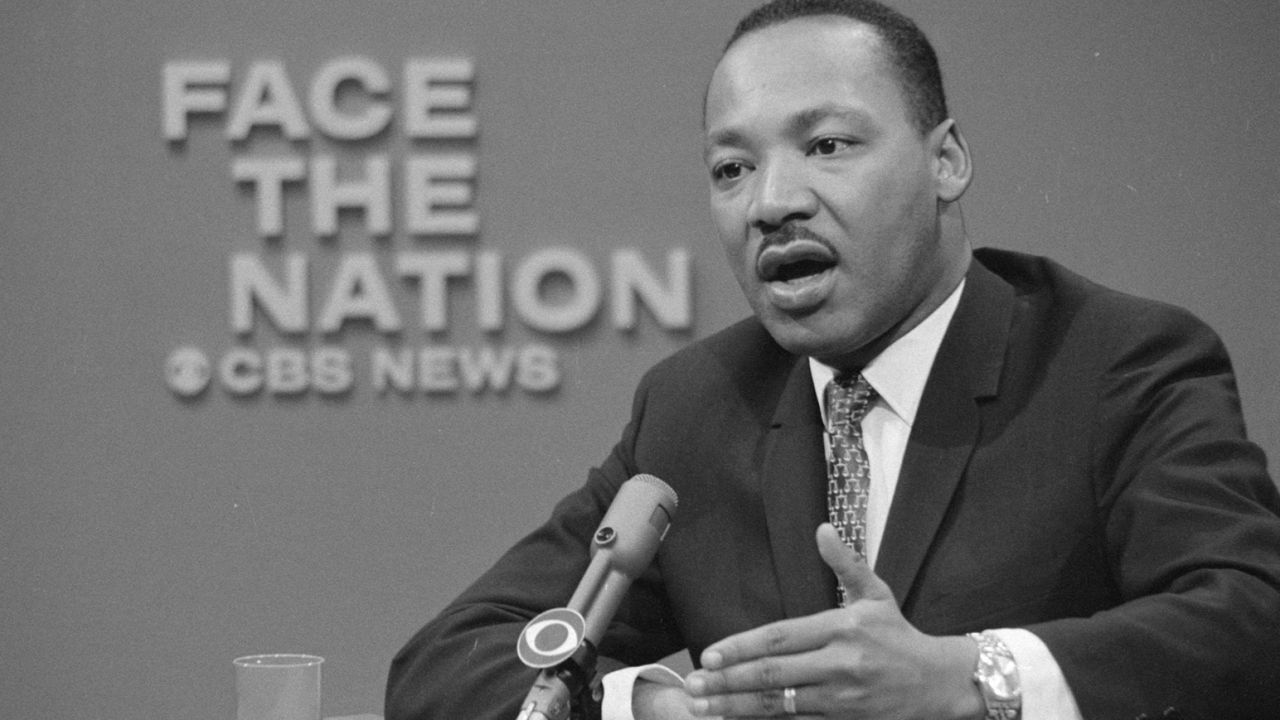

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. appeared on the television news program Face The Nation on April 16, 1967, to discuss his opposition to the war in Vietnam. As "one greatly concerned about the need for peace in our world and the survival of mankind, I must continue to take a stand on this issue," he said. (Photo by CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at Huffington Post.

This week marks the 50th anniversary of one of Rev. Martin Luther King’s most important speeches — an address at the prestigious Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967 in which he publicly denounced America’s war in Vietnam.

In the 1960s, the debate over war versus want was often called a battle between “guns” and “butter.” At a time when President Donald Trump has proposed a huge increase in the nation’s military budget by slashing programs for the poor, King’s speech, and the debate over the nation’s spending and moral priorities, is particularly relevant.

King called his speech “Beyond Vietnam — Time to Break Silence.” The title is misleading and may explain why some journalists and historians have claimed that this speech was King’s first public stance against that war. In fact he had spoken out against America’s involvement in that Southeast Asian country two years earlier and had gradually become more vocal in his opposition. The Riverside Church speech, however, garnered considerable national publicity because the anti-war movement was gaining momentum, President Johnson’s popularity was beginning to falter and a growing number of establishment figures were questioning both the moral and economic costs of having US combat troops and expensive weaponry in Vietnam.

By the time King delivered that speech, he had become increasingly frustrated by the slow pace of progress by both the civil rights and anti-poverty movements. His crusade for civil rights had begun more than a decade earlier with the successful Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, which forced the city to integrate its bus system. In the subsequent decade, he helped lead local campaigns in different cities, including Selma, Alabama and Birmingham, Alabama, where thousands marched to demand an end to segregation in buses, schools, jobs, restaurants, parks and voting rights. In defiance of court injunctions forbidding any protests, he was arrested at least 20 times, always preaching the gospel of nonviolence.

King recognized that the use of violence — by local police and sheriffs as well as by the Ku Klux Klan and other para-military hate groups — was the South’s way to oppose the struggle for civil rights. They bombed and burned churches and beat and killed civil rights activists. His own home was bombed and he received many death threats.

King began his activism in Montgomery as a crusader against the nation’s racial caste system, but the struggle for civil rights radicalized him into a fighter for broader economic and social justice. As early as 1961, in a speech to the Negro American Labor Council, King said, “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

He was proud of the civil rights movement’s success in winning the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act the following year. But he realized that neither law did much to provide better jobs or housing for the masses of black poor in either the urban cities or the rural South. “What good is having the right to sit at a lunch counter,” he asked, “if you can’t afford to buy a hamburger?”

When King launched a civil rights campaign in Chicago in 1965, he was shocked by the hatred and violence expressed by working-class whites as he and his followers marched through the streets of segregated neighborhoods in Chicago and its suburbs. He saw that the problem in Chicago’s ghetto was not legal segregation but “economic exploitation” — slum housing, overpriced food and low-wage jobs — “because someone profits from its existence.”

These experiences led King to develop a more radical outlook. King supported President Lyndon B. Johnson’s declaration of the War on Poverty in 1964, but, like the United Auto Workers’ Walter Reuther and others, he thought it did not go nearly far enough. As early as October 1964, he called for a “gigantic Marshall Plan” for the poor — black and white. He began talking openly about the need to confront “class issues,” which he described as “the gulf between the haves and the have nots.”

In 1966 King confided to his staff:

You can’t talk about solving the economic problem of the Negro without talking about billions of dollars. You can’t talk about ending the slums without first saying profit must be taken out of slums. You’re really tampering and getting on dangerous ground because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with captains of industry. Now this means that we are treading in difficult water, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong with capitalism. There must be a better distribution of wealth and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism.

Speaking to a meeting of Teamsters union shop stewards in 1967, King said, “Negroes are not the only poor in the nation. There are nearly twice as many white poor as Negro, and therefore the struggle against poverty is not involved solely with color or racial discrimination but with elementary economic justice.”

King’s growing critique of capitalism coincided with his views about American militarism and imperialism.

After the French withdrew from their former colony in Vietnam, the US gradually took charge of trying to prop up authoritarian governments in South Vietnam in order to keep the nationalist anti-colonial regime based in North Vietnam from uniting the country. America’s initial involvement was covert. Between the time of President John F. Kennedy’s death in November 1963 and the end of 1964, the number of American military personnel in Vietnam increased from 16,000 to 23,000.

In August 1964, a US destroyer was allegedly attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats while on patrol in the Gulf of Tonkin. Johnson used that incident to persuade Congress to authorize him to take whatever action he deemed necessary to deal with future threats to US forces or US allies in Southeast Asia — a statement called the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

At the time, few Americans were paying attention. Opposition to US presence in Vietnam was isolated to a handful of small peace groups. Not surprisingly, in his speech accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway on Dec. 10, 1964, King didn’t mention Vietnam.

The first major anti-war protests, centered on college campuses but also mobilizing people to demonstrate in Washington, DC, took place in early 1965. King was clearly paying attention. On March 2 that year, after a speech at Howard University, he responded to a question by declaring that America’s entanglement in Vietnam was “accomplishing nothing” and called for a negotiated settlement. A week later, as part of the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama to pressure Congress to pass a voting rights bill, King expressed his concern that “millions of dollars can be spent every day to hold troops in South Vietnam and our country cannot protect the rights of Negroes in Selma.” A few weeks later, while appearing on the TV show Face the Nation, he said that as “one greatly concerned about the need for peace in our world and the survival of mankind, I must continue to take a stand on this issue.”

While King and many others were marching in Selma to gain the right to vote, and being attacked by vigilante thugs as well as the Alabama state troopers, Johnson was escalating the war. That week, he sent 3,500 combat troops to Vietnam.

In early July 1965, speaking at Virginia State College, King made a significant leap in his public statements about Vietnam.

— Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“The time has come for the civil rights movement to become involved in the problems of war. … There is no reason why there cannot be peace rallies like we have freedom rallies. … We are not going to defeat Communism with bombs and guns and gases. We will do it by making democracy work. The war in Vietnam must be stopped. There must be a negotiated settlement with the Viet Cong. … The long night of war must be stopped.”

The following month, in his remarks to the annual meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (which he had founded and still headed), King called for a halt to US bombing in North Vietnam and suggested that the United Nations mediate the conflict to reach a peace agreement.

Despite these statements, King was not yet seen as a major voice in the anti-war movement or a significant opponent of American militarism. But he was inching closer to expressing those sentiments. His views were influenced by some of his close clergy friends, especially Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. In October 1965 Heschel spoke at an anti-war rally at the UN Church Center and proposed a national religious movement to end the war. He quickly went to work putting that idea into practice. He, Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, and Lutheran pastor Richard John Neuhaus founded the National Emergency Committee of Clergy Concerned About Vietnam in January 1966. Rev. William Sloane Coffin, the Yale chaplain, agreed to be acting executive secretary.

Their first act was to send a telegram to President Johnson, signed by 21 clergy — including King and Reinhold Niebuhr — urging the president to extend the bombing halt that had begun the previous Christmas and to pursue negotiations with the National Liberation Front and the North Vietnamese. Over the next few months, the group recruited additional clergy and organized rallies, fasts, vigils and other forms of protest, including a two-day fast to push Johnson to end US bombing of North Vietnam.

Although King signed that telegram to LBJ, he was still reluctant to speak out as part of the anti-war movement. He understood that his fragile working alliance with the president — who had been an ally in getting the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act through Congress in 1964 and 1965 — would be undone if he challenged the president’s leadership on the war. He was also concerned that if he expressed his opposition to the war, some would label him unpatriotic or even a Communist, undermining his still fragile reputation among America’s political leaders and the general public. (King was still being vilified by parts of the establishment, including the media and the FBI. In August 1966 — as King was bringing his civil rights campaign to Northern cities to address poverty, slums, housing segregation and bank lending discrimination — the Gallup Poll found that 63 percent of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of King, compared with 33 percent who viewed him favorably).

So King moved cautiously but steadily in making his views known. In January 1966 he gave a sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta in which he declared his opposition to the Vietnam War and described America’s involvement in that civil war as as a violation of the 1954 Geneva Accord that promised self-determination.

In December 1966, King testified before Congress about the nation’s spending priorities. He called for a “rebalancing” of the federal budget away from America’s “obsession” with Vietnam and toward greater support for anti-poverty programs at home.

On Jan. 31, 1967, Rabbi Heschel’s organization — renamed Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam (CALCAV) to be more inclusive — organized its first Washington, DC, rally. More than 2,000 people, clergy and laity, from 45 states participated, including the leaders of the nation’s major Jewish and Protestant denominations, but King did not participate. CALCAV’s leaders met with their congressional representatives and picketed in front of the White House. Heschel electrified the audience with his speech, “The Moral Outrage in Vietnam.” He said:

“Who would have believed that we life-loving Americans are capable of bringing death and destruction to so many innocent people? We are startled to discover how unmerciful, how beastly we ourselves can be. In the sight of so many thousands of civilians and soldiers slain, injured, crippled, of bodies emaciated, of forests destroyed by fire, God confronts us with this question: Where art thou?”

The next day, Heschel joined a small CALCAV delegation in a 40-minute meeting with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. They attempted, without success, to persuade him to suspend the bombing of North Vietnam and begin peace negotiations.

By early 1967, Heschel and CALCAV’s other leaders knew that King was preparing to make public his growing opposition to the war.

In January of that year King spoke at an anti-war conference in Los Angeles. His speech, which he entitled “The Casualties of the War in Vietnam,” argued that US power should be “harnessed to the service of peace and human beings, not an inhumane power [unleashed] against defenseless people.”

On March 25, 1967, King led a march of 5,000 people down State Street in Chicago to protest the war — the first anti-war march he had joined. At that march, he made what many view as one of his most pithy and memorable remarks of his life: “The bombs in Vietnam explode at home. They destroy the dream and possibility for a decent America.” He was clearly rehearsing for his speech at Riverside Church the following month.

Although some of his close advisers continued to discourage him from giving that speech, King decided it was time to put his influence as a moral voice in the service of the peace movement. On April 4, 1967, accompanied by Heschel, Amherst College professor Henry Commager, and Union Theological Seminary President John Bennett, King spoke to an overflow crowd of 3,000 at the prestigious Riverside Church. The event was sponsored by Heschel’s group, Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam.

“I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice,” King said.

He described the war’s disastrous consequences on America’s poor and on Vietnamese peasants. He declared that the US had a moral imperative to end the war through nonviolent means.

“I come to this platform tonight to make a passionate plea to my beloved nation. This speech is not addressed to Hanoi or to the National Liberation Front. It is not addressed to China or to Russia. Nor is it an attempt to overlook the ambiguity of the total situation and the need for a collective solution to the tragedy of Vietnam. Neither is it an attempt to make North Vietnam or the National Liberation Front paragons of virtue, nor to overlook the role they must play in the successful resolution of the problem. While they both may have justifiable reasons to be suspicious of the good faith of the United States, life and history give eloquent testimony to the fact that conflicts are never resolved without trustful give and take on both sides. Tonight, however, I wish not to speak with Hanoi and the National Liberation Front, but rather to my fellow Americans.”

King continued: “There is at the outset a very obvious and almost facile connection between the war in Vietnam and the struggle I and others have been waging in America. A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor, both black and white, through the poverty program. There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings,” referring to President Johnson’s anti-poverty initiatives, called the Great Society program.

“Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything on a society gone mad on war. And I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic, destructive suction tube. So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.”

King then observed:

“Perhaps a more tragic recognition of reality took place when it became clear to me that the war was doing far more than devastating the hopes of the poor at home. It was sending their sons and their brothers and their husbands to fight and to die in extraordinarily high proportions relative to the rest of the population. We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem. So we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. So we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago. I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.”

King’s next words linked the struggle for social justice with the struggle against militarism, in some ways echoing former President Dwight Eisenhower’s farewell speech in January 1961 in which he warned the country about the growing influence of what he termed the “military-industrial complex.”

In 1965, Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood erupted in violence, the first of what would become several years of riots, typically sparked by an incident of police abuse but rooted in the miserable housing, employment, education and other conditions facing the nation’s African-American poor. King noted:

“As I have walked among the desperate, rejected and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they asked, and rightly so, ‘What about Vietnam?’ They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.”

Moving beyond the Vietnam war, King called for the US to “undergo a radical revolution of values,” suggesting that “we must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society.” He observed:

When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

The crux of his argument came a few paragraphs later: “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

(You can listen to the recording of the speech here and read the entire text here).

King knew that his speech would stir controversy, not only among his enemies but also among some civil rights groups. The NAACP, the nation’s largest civil rights organization whose leaders sometimes viewed as a rival as well as an ally, issued a statement criticizing King for linking the civil rights and peace movements, saying, in effect, that he should stick to his expertise in civil rights and not venture into the debate over foreign policy.

Three days after King’s speech, The New York Times — then considered the voice of the nation’s moderate establishment — published an editorial entitled “Dr. King’s Error,” that blasted him for his comments. It began:

“In recent speeches and statements the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. has linked his personal opposition to the war in Vietnam with the cause of Negro equality in the United States. The war, he argues, should be stopped not only because it is a futile war waged for the wrong ends but also because it is a barrier to social progress in this country and therefore prevents Negroes from achieving their just place in American life. This is a fusing of two public problems that are distinct and separate. By drawing them together, Dr. King has done a disservice to both. The moral issues in Vietnam are less clear-cut than he suggests; the political strategy of uniting the peace movement and the civil rights movement could very well be disastrous for both causes.”

The Washington Post declared that King had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people.” TIME magazine called the speech “demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi.”

Despite the criticism, King was undeterred. On April 15, 1967 — 11 days after his Riverside Church address — he joined forces with popular singer Harry Belafonte and famous pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock at a march in New York City of 100,000 protesters from Central Park to the United States — the largest anti-war demonstration up until then. King’s wife, Coretta, participated in another anti-war march that day in San Francisco.

— Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In early 1968 King told journalist David Halberstam, “For years I labored with the idea of reforming the existing institutions of society, a little change here, a little change there. Now I feel quite differently. I think you’ve got to have a reconstruction of the entire society.”

King kept trying to build a broad movement for economic justice that went beyond civil rights. In January 1968 he announced plans for a Poor People’s Campaign, a series of protests to be led by an interracial coalition of poor people and their allies among the middle-class liberals, unions, religious organizations and other progressive groups, to pressure the White House and Congress to expand the War on Poverty. At King’s request, socialist Michael Harrington (author of The Other America in 1962, which helped inspire the war on poverty) drafted a Poor People’s Manifesto that outlined the campaign’s goals.

King continued to commit himself to ending the war. He worked with Spock and others to create “Vietnam Summer,” a volunteer project to increase grass roots peace activism to encourage candidates for president and Congress in 1968 to oppose the war. His speeches continued emphasize the need to end militarism in order to address America’s domestic problems. He talked about the three major crises facing America: poverty, racism and the war in Vietnam. At a sermon at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC, on March 31, 1968, King said that he was “convinced that [Vietnam] is one of the most unjust wars that has ever been fought in the history of the world.”

Later that day, President Johnson stunned the country when he announced that he would not seek a second term as president. His escalation of the war without any signs of success had sapped his public support. King’s growing involvement in the anti-war movement surely contributed to the political environment that led LBJ to bow out.

In April, King traveled several times to Memphis, Tennessee — at the invitation of his friend Rev. James Lawson — to help lend support to African-American garbage workers who were on strike to improve pay and safety conditions and to win recognition for their union.

On April 4, 1968 — exactly a year after his speech at Riverside Church — the 39-year-old King was assassinated while standing on the balcony of his Memphis motel.

King’s public opposition to the war had helped shift public opinion against US involvement, giving candidates for office room to run on anti-war platforms. One of them was Sen. Robert F. Kennedy from New York. After LBJ announced he would not seek re-election, Kennedy entered the presidential race. He, too, had steadily become more outspoken against the Vietnam war. His campaign’s two major themes echoed what King had been saying — that the nation must end its involvement in Vietnam so it could wage a major war against poverty at home.

Kennedy was the favorite to win the Democratic nomination for president at the party’s August convention in Chicago. It is likely that King would have embraced Kennedy’s campaign, which had a good chance of defeating Richard Nixon, whom the Republicans nominated as their president. Had Kennedy won the presidency, and taken office in January 1969, US involvement in Vietnam would have probably ended within a year.

Of course, history took a different turn. Kennedy was killed in Los Angeles in June on the night he won the California primary. Rather than Kennedy, the Democrats nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who had reluctantly but loyally supported LBJ’s Vietnam policy. Nixon beat Humphrey in November, claiming he had a “secret plan” to end the war. Instead, he further escalated the war, although he so by using air power while eventually withdrawing US combat troops.

The last American combat troops didn’t leave Vietnam until August 1972, but US advisers and weapons remained in the country for several more years. Nixon was re-elected in 1972 but was soon caught in the Watergate scandal, forcing him to resign in August 1974, replaced by Vice President Gerald Ford. America’s incompetent puppet government in South Vietnam continued to lose ground to the North Vietnamese troops. On April 30, 1975, the last Americans, 10 Marines from the embassy, left Saigon, ending the US presence in Vietnam. By later that day, the Viet Cong flag flied from the presidential palace and America’s one-time allies surrendered. The war was over.

Fifty years after King’s Riverside Church speech, the US remains embroiled in several ground wars as well as a war on terrorism, a war against Muslims and a war against immigrants. President Trump has not only proposed a $54 billion increase the military budget but also recommended massive tax cuts, both of which would be accomplished through draconian cuts to programs that serve the poor and the elderly.

As the resistance to Trump’s presidency and his priorities gains momentum, it is worth recalling King’s words a half century ago. The United States, he declared, is “on the side of the wealthy, and the secure, while we create a hell for the poor.” We cannot solve our domestic problems and help promote global peace until we “give up the privileges and the pleasures that come from the immense profits of overseas investments.”

Today, we still need what King called a “radical revolution of values” that emphasizes social justice rather than militarism and economic nationalism.