Mass incarceration in the US impacts the health of prisoners, prison-adjacent communities and local ecosystems from coast to coast. (Photo by Dave Nakayama/ flickr CC 2.0)

This post originally appeared at Truthout and at Earth Island Journal.

Matthew Morgenstern is convinced his Hodgkin’s lymphoma was caused by exposure to toxic coal ash from the massive dump right across the road from SCI Fayette, a maximum-security prison in LaBelle, Pennsylvania, where he is currently serving a 5- to 10-year sentence. “In 2010 and until I left in 2013, the water always had a brown tint to it. Not to mention the dust clouds that used to come off the dump trucks … which we all breathed in…. Every single day I would wake up and there would be a layer of dust on everything,” he writes from inside the prison. When Morgenstern was sent back to SCI Fayette in 2016 after he violated parole, he found that the dust issue had abated a bit — work at the dump has been stalled for a year due to litigation — but the water still runs brownish and sometimes has “a funky smell.” He says he knows that the environment in and around the prison is still “messed up” and he’s concerned that his immune system, already weakened from fighting and overcoming cancer, won’t be able to withstand another onslaught of toxic exposure. “I myself have no doubt that if I’m kept here at Fayette, I will once again become sick,” he writes.

Likewise, in Navasota, Texas, Keith Milo Cole and John Wesley Ford, aging prisoners at the Wallace Pack Unit, worry about how their prolonged exposure to arsenic-laced water and extreme heat during summer months may have affected their health over the long term. Like Morgenstern, Cole says the water at his unit was brown until a federal judge ordered the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) to provide the prisoners safe drinking water. “It used to be where you could take a white wash rag and put it in the sink and water would run on it about 10 or 15 minutes, and it would actually turn brown,” says Cole, who is serving a life sentence.

Farther west, in California, Kenneth Hartman was nearly 30 years into a life sentence when he contracted valley fever in 2008 at the California State Prison in Lancaster. The infection, caused by inhaling a soil-dwelling fungus, can be devastating. Though it is often mistaken for the common flu, it can kill people or leave those infected with lifelong symptoms. “The intensity or severity [of my symptoms] kept increasing to the point that I clearly remember thinking, if I get any sicker, I’m going to die,” Hartman says, writing from Lancaster where he is still incarcerated. “My physical strength was near to zero. … I had a persistent dry cough, severe night sweats and bouts of vertigo that rendered me practically immobile.”

The plight of these prisoners points to a nationwide problem that’s inextricably linked to power imbalances within the US criminal legal system — a system in which prisoners are often out of sight and thus out of the public mind.

As a special investigation by Truthout and Earth Island Journal shows, the toxic impact of prisons extends far beyond any individual prison, or any specific region in the United States. Though some prisons provide particularly egregious examples, mass incarceration in the US impacts the health of prisoners, prison-adjacent communities and local ecosystems from coast to coast.

A 700 Percent Increase in Prisoner Population

The US locks up more people per capita than any other nation in the world. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, currently some 2.3 million people are confined in more than 6,000 prisons, jails and detention centers operated by multiple federal, state, county and private actors. That’s about the population of Houston, Texas, the fourth-largest city in the nation.

Since the 1970s, the US has seen a 700-percent increase in the number of people imprisoned, a result of the growth in “tough on crime” and “war on drugs” policies, as well as a concerted effort to control and minimize the power of social movements and other forms of resistance from within communities of color, says David Naguib Pellow, a professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who’s writing a book on prisons and environmental justice. The rate at which we lock people up today is some five times higher than most countries, even though the crime rate in the US is comparable to that of other stable, industrialized nations.

Holding large groups of people in closed facilities brings with it a host of associated civil and human rights problems — problems that have been well documented. But until recently, not much thought or research had been expended on the connections between mass incarceration and environmental issues, that is, problems that arise when prisons are sited on or near toxic sites, as well as when prisons themselves becomes sources of toxic contamination.

Paul Wright, executive director of the Human Rights Defense Center, was among the few people who began to look into this connection on a broad scale nearly three decades ago. When Wright was serving time in Washington state’s McNeil Island prison in the 1990s, the tap water there too, used to run brown. “Yet the prison officials would be putting up signs saying the water is safe to drink,” he recalls. “There were a lot of environmental issues going on within the prison. It got me thinking. Just seeing how the prisons were on everything, I didn’t think they would be any better on the environment.”

So Wright, who along with fellow prisoner Ed Mead, had recently started publishing Prison Legal News — a magazine where prisoners and their families speak up about criminal legal policy and reform — began filing public records requests for water pollution related complaints in state and federal prisons across the country. “Sure enough, we got all kinds of stuff back saying that the prisons were literally sources of toxic pollution,” he says. In 2007, Prison Legal News published findings from 17 states exposing issues related to sewage and sanitation violations in dozens of prisons.

Once he got out in 2003 after serving 17 years, Wright expanded Prison Legal News into the Human Rights Defense Center, a Florida-based nonprofit that advocates on behalf of people held in US detention facilities. In 2014, the Center launched the Prison Ecology Project, which Wright says aims “first and foremost” to map the extent of the intersections between mass incarceration and environmental degradation, and then “do something to change it.”

“People [on the outside] generally aren’t thinking of prisons and jails as environmental problems or as places where people have legitimate concerns about the environment,” Wright says.

It’s well known that low-income communities and communities of color are disproportionately impacted by environmental degradation. Polluting facilities are more likely to be built in these communities, and environmental regulations are often less stringently enforced in these neighborhoods. This legacy of environmental injustice extends to the siting of prisons, which, too, are often located in or close to low-income communities. Additionally, they are built on some of the least desirable and most contaminated lands in the country, such as old mining sites, Superfund cleanup sites and landfills. According to a GIS [geographic information system] analysis of a 2010 dataset of state and federal prisons by independent cartographer Paige Williams, at least 589 federal and state prisons are located within three miles of a Superfund cleanup site on the National Priorities List, with 134 of those prisons located within just one mile.

“A lot of people, when they think of environment and toxic polluters, they think corporations, and they think that the government is somehow a solution to this problem,” Wright says. “The prison ecology issue turns that whole thing on its head because in these cases it’s the government that’s chosen to build these prisons on toxic waste sites or allowed them to become sources of toxic waste. And it is literally holding people at gunpoint at these sites and exposing them.”

Former Industrial Sites “Recycled” for Prisons

To get to SCI Fayette, where Matthew Morgenstern is incarcerated along with more than 2,000 other men, you may have to pass through the borough of Brownsville — a small industrial area along the Monongahela River southwest of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This used to be a bustling business center connected to the steel industry, but today downtown Brownsville wears the look of a town that’s well past its glory days.

America’s Rust Belt is scattered with places like this, where the retreat of industries in the 1970s left working-class folks without opportunities. In many of these places, prisons began to fill in the gap, occupying lands left degraded by industrial activities and offering often-unfulfilled promises of employment to impoverished communities.

The land being “recycled” has, in many cases, already been devastated — to an extent that the construction of a prison may be seen as its only “acceptable” use.

“One of the patterns that we see is where corporations have come in, they pillage the environment, be it by mining, forestry or whatever, and then when everything has been exhausted, when trees have been cut down, every last grain of ore has been ripped from the soil, and everything has been contaminated and poisoned in the process, the final solution is, okay now we’re going to build a prison here,” Wright says.

SCI Fayette — which is located in the small rural community of LaBelle, about a 12-minute winding drive from Brownsville — is a perfect example of this. The 237-acre men’s prison began operating in 2003 on one corner of what, in the 1940s through the 1970s, was one of the largest coal preparation plants in the world, where coal from nearby mines was washed and graded. The “cleaned” coal was then shipped off to power plants and other markets, while the remaining coal refuse was dumped on and around the hilly, 1,357-acre site. By the mid-1990s, when its owners filed for bankruptcy and abandoned the site, an estimated 40 million tons of coal refuse had been dumped there. At some places the waste piled up some 150 feet.

In 1996, the property was purchased by a local company, Matt Canestrale Contracting (MCC), which entered into a contract with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to dump coal ash — waste produced by burning coal in power plants — on the site as part of a land “reclamation” effort. Since it opened in 1997, more than 5 million tons of coal ash has been deposited at the dumpsite, which is right across the road from SCI Fayette.

The problem with coal ash is that it’s way more toxic than unburned coal waste as it contains higher concentrations of heavy metals and minerals, including mercury, lead, arsenic, hexavalent chromium, cadmium, boron and thallium. At unlined sites, like LaBelle, contaminants can leach into the local water and fine “fugitive dust” can blow into the air.

Coal ash can cause or contribute to many serious health conditions, including respiratory problems, hypertension, heart problems, brain and nervous system damage, liver damage, stomach and intestinal ulcers, and many forms of cancer, including skin, stomach, lung, urinary tract and kidney. Therefore, many environmental experts say the risks posed by such reclamation efforts outweigh the so-called benefits.

Right when the coal ash dumping started, LaBelle residents began complaining to the DEP that fugitive dust was making them sick. Over the years, they reported suffering from respiratory problems, kidney failure, and several types of cancer. But the DEP did little more than issue fines. It allowed the prison construction to go forward, essentially putting the health of the entire prison population, as well its staff, at risk.

In 2013, Citizens Coal Council, a coal industry watchdog, filed a federal lawsuit against MCC, alleging that the company was responsible for polluting the local air and water due to its failure to curb fugitive dust. The suit noted that 50 families lived in LaBelle, but made no mention of the prisoners at SCI Fayette.

However, prisoners and staff at SCI Fayette have been experiencing health issues that are similar to those reported by local community members. In fact, SCI Fayette is also exposed to two other potential sources of pollution: The boiler system for the prison burns coal for its power (and creates additional coal ash waste), and a new coal terminal along the riverbank, right next to the prison, transfers 3 to 10 million tons of coal per year from boats to rail.

Word of the prisoners’ plight began filtering out, but it wasn’t until 2013 that it reached the ears of Dustin McDaniel, the director of the Abolitionist Law Center (ALC), a Pittsburgh-based public-interest law firm that works on cases involving human rights abuses in prisons.

Dustin McDaniel of the Abolitionist Law Center has been campaigning to shut down SCI Fayette in Pennsylvania. He says the well-being of prisoners isn’t taken into consideration when agencies decide where to site prisons. (Photo by Nina Young)

In September 2014, based on a yearlong review of prison medical records, interviews with prisoners, former prisoners and residents of LaBelle, ALC along with the Human Rights Coalition, an advocacy group that fights for prisoners’ civil rights, released “No Escape,” a report outlining the health issues people were experiencing in the prison. According to the report, 81 percent of the 75 prisoners who responded to a health survey ALC sent out claimed to suffer from respiratory, throat and sinus conditions; 68 percent experienced gastrointestinal problems; 52 percent reported adverse skin conditions; and 12 percent said they were diagnosed with a thyroid disorder. The report also noted 11 of the 17 prisoners who died at SCI Fayette between 2010 and 2013 had died of cancer.

All of these numbers, McDaniel says, were well above what would be considered normal, though he acknowledges that the health survey was limited in its scope, given the number of respondents. “We don’t have a rock-hard analysis that says ‘yes, that’s the causation’ but there’s certainly a lot of correlation,” he says.

After the ALC report came out, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (DOC) conducted “a comprehensive review” of the conditions at the prison and issued a statement in December 2014 saying it had found “no scientific data to support claims of any unsafe environmental conditions or any related medical issues to exist at SCI Fayette.” It said the prison’s water supply had been tested and it had met all relevant drinking standards. The department’s review, however, doesn’t appear to have included looking into the air quality at the prison.

ALC is currently crunching the numbers on a second, more detailed, health survey that it sent out to all the prisoners at SCI Fayette in 2015 and received 650 responses to. The Center is also pushing the state corrections department to conduct an independent and comprehensive health study of the prisoners, prison staff and community members.

The state corrections department did not respond to repeated requests for interviews. Instead, in an emailed response to a few questions, press secretary Amy Worden said that the department last conducted an air quality test, for mold and fly ash, in October 2016 and “the results were within parameters set forth by OSHA and ASHRAE and did not require any action.” The DOC didn’t provide us with a copy of the report or any supporting data, so it’s unclear what that test actually revealed.

Worden also said potable water at the facility is tested for bacteria, and TTHM and HAA5 — byproducts of adding chlorine to disinfect water — on a monthly basis, in addition to the testing required of Tri County Joint Municipal Authority, which supplies water to the prison. “We are confident that the water supply at SCI Fayette is safe,” she said.

It’s true that the prison’s drinking water comes from farther upstream, so any contamination issues the water might have can’t be linked to the coal ash dump. However, the Municipal Authority’s own water quality reports, dating back to 2013, show that it has consistently exceeded the EPA’s maximum levels for TTHMs, exposure to which is associated with adverse health effects, including cancer.

In June last year, Citizens Coal Council and MCC entered an interim agreement on the 2013 lawsuit under which the company agreed to a one-year moratorium on disposal of coal ash at the site. The dump is scheduled to start operating again this July, though given recent market trends, where cheap natural gas is driving power generation away from coal, its long-term future is uncertain.

That prospect is small consolation for prisoners like Morgenstern, who say nothing’s really changed inside SCI Fayette and people are still getting sick at higher rates than in most prisons. “They [still] constantly blow out a lot of grey dust from the [prison] vents, which [causes] a little pain to my sinuses and I’m always having to blow my nose. … I’d say probably 65 to 75 percent of us here deal with this issue,” he said over the phone in April. “Honestly, I would like to see this place shut down because I know the environmental conditions here would take at least 50 to 60 years to heal. It’s putting everybody at risk.”

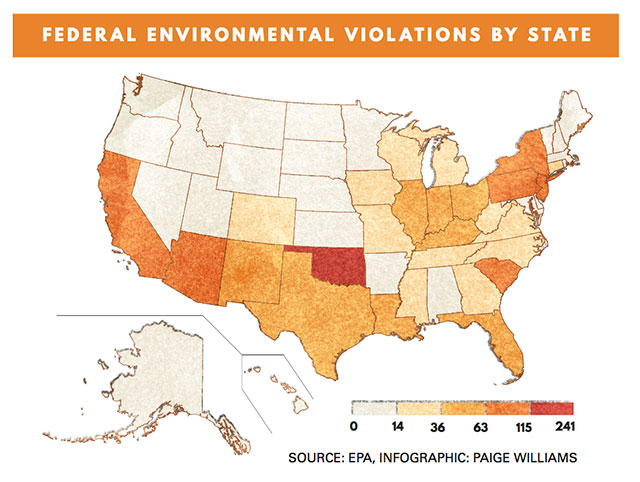

Violations of federal environmental laws in prisons over the past five years.

In California, Sitting Ducks for Valley Fever

There’s not much by way of scenery around Avenal State Prison in California’s Central Valley. It’s mostly flat farmland, a large solar array, signs warning of high winds and dust, and trucks lumbering down Highway 33 past the octagon of razor-wire fencing surrounding the prison. The occasional crop duster flies overhead, surprisingly close to prison grounds. Inside the fence, the scene is even starker — drab buildings with small slits for windows, dusty open space and sparse, treeless lawns that the prisoners use for soccer games.

At Avenal, as at other Central Valley prisons, incarcerated people are sitting ducks for valley fever, which is endemic to the dry Southwestern US. Research indicates that prisoners are much more likely to contract the disease than are members of the general population. In 2011, a particularly bad year, infection rates for the highest risk California state prisons were dozens of times above those in nearby communities, according to Centers for Disease Control data. Although the fungus is poorly understood, researchers suspect that out-of-town prisoners bused to the Central Valley are especially susceptible because they are not native to the region. Locals may develop some kind of immunity that shields them from the worst valley fever symptoms.

In the past decade, more than 3,500 California prisoners have become sick from valley fever and more than 50 have died from it. Though infection rates decreased significantly after 2011, to fewer than 100 cases each in 2014 and 2015, last year saw another spike with 267 prisoners infected.

The jump can likely be tied to weather patterns: Intense rains — which allow the fungus, coccidioidomycosis (or “cocci”), to grow — followed by prolonged dry periods seems to lead to higher infection rates. Experts predict infection rates will continue to climb throughout the Southwest due to a combination of drought, climate change and intensive agriculture.

Avenal State Prison, along with the nearby Valley State Prison, has struggled with particularly high valley fever infection rates.

In 2013, a federal court order mandated that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation remove African-American and Filipino prisoners — who are genetically at a much higher risk of getting seriously sick from valley fever — from Avenal and Pleasant Valley state prisons. Some 2,600 prisoners were transferred. Then in 2015, the department began offering all California prisoners the option of taking a newly available valley fever immunity test and diverting those who test vulnerable from these two prisons. Prisoners can decline the skin test, but cannot decline to be transferred if they test vulnerable.

However, some prisoners are still getting sick. Todd Love, who is white, declined the skin test because he has family in King County, where Avenal is located, and didn’t want to risk transfer if he tested negative for immunity. Love, 51, has spent nearly 25 years in prison, the last two years at Avenal. Last year, along with, by his estimates, at least 30 others, Love came down with the infection.

“It’s the closest to death I’ve ever been,” he says, sitting in the shadeless yard at Avenal. Though he is largely recovered, Love says the illness definitely took a toll on him.

The risk of prisoners contracting valley fever extends beyond the Central Valley, as evidenced in the case of Kenneth Hartman, who’s incarcerated in Lancaster, California. Hartman eventually recovered from his 2008 infection after spending several weeks “handcuffed to a bed in an outside hospital” on an intravenous antifungal. When that didn’t work, and his kidneys almost failed, he was put on different medication, which worked. He now has low kidney function, which he believes is related to his years of taking antifungal drugs.

“Prisons found to be a serious health risk need to be closed,” Hartman writes in a letter from prison. “The changes made [to address valley fever] are about managing risk and trying to avoid lawsuits, not about fixing the problems of a massively dysfunctional prison system.”

Life-threatening exposure isn’t always tied to a particular, site-specific source of pollution. Problems like water contamination or pesticide exposure can occur at prisons regardless of their location on seemingly benign lands.

In other cases, prison conditions can be made worse by climate change.

As in California, 2011 was a deadly year in Texas prisons. That summer, 10 prisoners died of heat stroke in state-operated prison units. The deaths are among 22 in-custody hyperthermia deaths that the state has acknowledged in its 108 prisons units. Seventy-nine of those units still lack air-conditioning in 2017, even as summer temperatures regularly soar beyond 100 degrees.

“The beds and cubicle wall are metal. [During summer] they are hot and can’t be laid on or touched, like touching the hood of a car that has sit (sic) in the sun on a 130-degree day,” Ford writes about the conditions at the Wallace Pack Unit, a Type I geriatric prison incarcerating predominantly elderly and disabled prisoners who require continuous medical care. “Most of us try to wet our sheets and the cement floor. We lay in the water, put the sheet over us while blowing the fan under the sheet, to keep the body temps down.”

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s solution during periods of extreme heat was to tell Pack Unit prisoners to simply drink more water, recommending up to two gallons of water a day on extremely hot days. There was just one problem: The water at the Unit contained between two-and-a-half to four-and-a-half times the level of arsenic permitted by the EPA. Arsenic is a carcinogen. The prisoners drank thousands of gallons of the arsenic-tainted water for more than 10 years before a federal judge ordered TDCJ to truck in clean water for the prisoners last year. TDCJ installed a modern filtration system in January.

Last year, Todd Love, who is serving time at Avenal State Prison in Central Valley, California, suffered from valley fever, an infection that’s endemic to the region. “It was really scary,” he says. (Photo by Ian Umeda)

Both Ford and Cole worry about how prolonged exposure to arsenic may have affected their medical conditions. Cole has been diagnosed with severe coronary artery disease, Type 2 diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol and has had two stent implants. Ford has seven stent implants, high blood pressure, and “serious issues” with his bladder and kidneys that he says are “from the chemicals.”

Cole is the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit challenging conditions at the Unit. TDCJ officials are currently appealing the suit’s status as class action in federal court.

Our investigation found that violations of drinking-water contamination, including by arsenic and lead, are not isolated to prisons like Wallace Pack, but are present at many prisons, jails and detention centers across the nation. In fact, according to the EPA’s enforcement database, federal and state agencies brought 1,149 informal actions and 78 formal actions against regulated prisons, jails and detention centers during the past five years under the Safe Drinking Water Act, more than under any other federal environmental law.

The database, which did not include penalty information for those enforcement actions, gives just a glimpse of the actual extent of environmental violations at prisons: It contains records for just over 1,000 of the country’s estimated 6,000 prisons and jails. The discrepancy, the EPA says, may be attributed to incomplete data entry, as well as the fact that it contains only facilities that have at some point been found in violation of federal environmental laws. It’s possible that many more violations simply aren’t reported.

Prisons’ Legacy of Water and Air Pollution

Though many of mass incarceration’s most severe environmental health implications affect prisoners most directly, prisons themselves can become a source of pollution for nearby residents and ecosystems.

Take the California Men’s Colony state prison (CMC), located about 10 miles from the stunning Pacific Ocean coastline in San Luis Obispo. The prison has a legacy of water pollution dating back nearly two decades, and a history of pollution-related penalties going back to at least 2004, when the prison was fined $600,000 by the regional California water quality control board for spilling 220,000 gallons of raw sewage into nearby Chorro Creek. The creek flows into Morro Bay, a state-designated marine protected estuary. Despite upgrades to the prison’s old wastewater treatment plant after the 2004 spill, problems continued: In 2008 state water officials levied another $40,000 in fines against CMC for spilling another 20,000 gallons of sewage that resulted in the bay being closed for recreational use and fishing for several days. The prison got into hot water again in 2014, when the EPA levied $373,500 in fines for Clean Water Act violations. And still the pollution persisted: Spills were documented again in 2015 and in January of this year.

The California Men’s Colony may be one of the most egregious water polluters, but it is certainly not alone. Prisons from Virginia to Washington state have been cited for violating point source pollution regulations under both state and federal water laws, as well as for falsifying water pollution reports. For example, Monroe Correctional Complex, the Washington state prison northeast of Seattle where Wright served some time, has been caught in violation on multiple occasions. The prison got caught in 2004 for falsifying water pollution reports to cover up excess fecal coliform levels in water discharged into the Puget Sound. Additionally, records obtained by the Human Rights Defense Center indicate that Monroe spilled or dumped roughly half a million gallons of contaminated water between 2008 and 2015, polluting nearby rivers and wetlands.

Over the past five years, federal and state agencies have brought 132 informal actions and 28 formal actions against regulated prisons and jails under the Clean Water Act, resulting in $556,315 in fines.

Prisons can have a significant impact on local air quality as well. In some cases, this comes from on-site sources, like industrial activities associated with prison labor programs or local power generation. Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections, for instance, came under scrutiny from the EPA in 2010-11 because coal-fired boilers at four state prisons were exceeding federal standards for particulate matter, sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxide. All four facilities were required to clean up their act, and the DOC was required to pay a $300,000 fine.

An analysis of EPA data indicates that 92 informal actions and 51 formal actions were brought against prisons, jails and detention centers across the country under the Clean Air Act during the past five years, though the total fines for these violations amounted to only $97,048.

Air quality is also an issue in the Central Valley — where 16 of California’s 33 state prisons are located, in addition to federal facilities and local jails.

Debbie Reyes, who runs the California Prison Moratorium Project, points to emissions from prison-related traffic, including visitor vehicles and the many diesel trucks bringing in supplies. In parts of the Central Valley, such as San Joaquin Valley, which don’t meet state standards for ozone levels and particulate matter, the prison industry is yet one more source of air pollution heaped upon an overburdened community. Reyes also notes that prisons can consume a lot of water. In an arid area like the Central Valley, this can be particularly problematic during droughts for cities like Avenal and Porterville that share water resources with overcrowded prison systems.

EPA Guidelines Should Apply to Prisoners, Too

Environmental issues at the US’ extensive patchwork of prisons and jails are regulated by a complicated combination of local, state and federal regulatory agencies, such as local water boards and air pollution boards, as well as pesticide, hazardous waste and toxics control agencies. This makes it difficult to grasp the entire extent of the impact prisons have on the environment and on human health in this country.

The only agency with nationwide oversight of these facilities is the EPA. As with other industries, in order to ensure compliance with federal environmental laws, the EPA conducts on-site monitoring of prisons and jails, responds to public tips and complaints, and encourages self-disclosure of violations.

But the Prison Ecology Project argues that the EPA isn’t doing nearly enough, especially when it comes to protecting prisoners’ health and environmental rights. It points out that under a 1994 executive order signed by President Bill Clinton, all federal agencies are meant to weigh the impacts of their actions on low-income communities and communities of color that have been disproportionately impacted by environmental pollution.

The EPA does have an environmental justice program, but the Prison Ecology Project says the agency does not apply its environmental justice guidelines to prisoners — despite the fact that the majority of US prisoners are from low-income communities and are people of color — at least in part because the population data the agency uses does not take prisoners into account. This omission, it says, has implications for how the EPA conducts prison inspections and prison-related environmental reviews, and permits construction of new prison facilities.

The Prison Ecology Project and Human Rights Defense Center are pushing to change this. Last year, in anticipation of the EPA’s development of its EJ 2020 Action Agenda Framework, Human Rights Defense Center submitted a public comment calling on the agency to “ensure that the millions of prisoners in this country receive the protections that are intended under” Clinton’s environmental justice executive order. More than 130 environmental, social justice and prisoners’ rights organizations signed on to the letter.

“There are some basic things that come from prisoners being recognized” in the 2020 Action Agenda, says Prison Ecology Project cofounder Panagioti Tsolkas. “For starters, environmental permits would have to take the impact on prison populations into account.” Tsolkas says that over the long term, incorporating prisoners into the EPA’s environmental justice analysis would help the environmental movement realize that “there are these invisible populations that could consider themselves as part of the environmental movement and strengthen it.”

The EPA did not respond to repeated requests for interviews with staff in its environmental justice and enforcement offices. However, in an emailed statement, the agency said “data limitations still exist regarding the amount of real-time information available on transient, temporarily relocated, and displaced populations,” but that the agency was working within those challenges.

Prisoners’ rights and environmental organizations also point to the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) failure to consider prisoner well-being in decisions about where to site new facilities, particularly during the environmental review process required under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA).

As McDaniel of the Abolitionist Law Center (ALC) puts it, “Most of the [Environmental] Impact Statement for a prison will be devoted to issues of the local economy and environment external to the prison, such as traffic, commerce, employment, burden on the local health care system, or the local utilities system, as well as impact on any wildlife and natural resources. In practice, the physical health and general well-being of prisoners are not taken into consideration through this process.”

For instance, the prison bureau’s 2015 Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for its proposed prison on a former mountaintop-removal mining site in Letcher County, Kentucky, fails to consider environmental impacts on the estimated 1,200 people who will be held at the new prison, if it is built. Several groups, including Human Rights Defense Center, the ALC and the Center for Biological Diversity, challenged the EIS on these grounds. A revised EIS, released earlier this year, includes some mention of health implications for prisoners, but does not provide the kind of robust discussion sought by advocates. Human Rights Defense Center contends that this revised EIS might be the only example of an environmental review in which the BOP made any mention of prisoner health.

The BOP, too, declined our reporting team an interview and instead sent an emailed statement saying that it does comply with NEPA requirements and considers the “health and environmental impacts on the prison population when conducting environmental assessments.”

The EPA, incidentally, hasn’t always taken such a subdued, reactive role on the issue of toxic prisons. In fact, in 2003, the agency summed up the environmental impact of prisons like this:

“Correctional institutions have many environmental matters to consider in order to protect the health of the prisoners, employees, and the community where the prison is located. Some prisons resemble small towns or cities with their attendant industries, population, and infrastructure. Supporting these populations … requires heating and cooling, wastewater treatment, hazardous waste and trash disposal, asbestos management, drinking water supply, pesticide use, vehicle maintenance and power production, to name a few potential environmental hazards. … The US Environmental Protection Agency has been inspecting correctional facilities to see how they are faring. From the inspections, it is clear many prisons have room for improvement.”

This statement originated from the webpage of EPA’s Region 3 office, which covers the mid-Atlantic states — Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland and Washington, DC. For nearly 10 years, the regional office ran a “Prisons Initiative” to improve environmental compliance at prisons and jails. Under the initiative, the EPA conducted inspections at 15 prisons throughout the region to assess compliance, in addition to outreach and training work. Several of the prisons inspected were issued fines in excess of $100,000.

The initiative ended in 2011 as, according to an agency statement, the “EPA felt prisons in the Mid-Atlantic region were able to ensure environmental regulation compliance by themselves.” Information about the initiative, which was available on the EPA website for more than 15 years, was removed in 2015.

Now, as the Trump White House seeks to close the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice entirely, many protections for marginalized communities look to be on the chopping block. And that means the opportunity to ensure those protections for prisoners may soon be even further out of reach.

The Need for a Collective Shift in Mindset

In the absence of any concrete environmental and public health protections, most actions to improve environmental conditions in prisons seem to be taken only when incarcerated people, prison staff, prisoner rights advocates and environmental groups make enough noise, usually in the form of a lawsuit.

At California’s Avenal State Prison, and the Wallace Pack Unit in Texas, relief for prisoners has been primarily achieved through the courts. Wallace Pack’s prisoners got clean water only after they sued the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. If the Pack plaintiffs’ class-action lawsuit prevails, it could set a major precedent in the state, leading to more such lawsuits and increasing the pressure on officials to air-condition prisons.

As in Texas, it took outside pressure to really get the ball moving on combatting valley fever in California. In 2005, the same year that the cocci fungus began picking up steam in prisons across the state, a federal judge ruled that medical care for state prisoners was so inadequate that it violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. The judge appointed a medical receiver to oversee the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s medical care system. But it took a court order in 2013 to get the corrections department to start following the receiver’s 2011 recommendation and start moving “high risk individuals” out of prisons with the highest valley fever infection rates.

Over in Pennsylvania, the SCI Fayette prison guards’ union fought for access to bottled water for staff and won. But the prisoners there still continue to drink tap water. ALC’s McDaniel says the Center’s plans to file a lawsuit on behalf of the prisoners is “stuck in limbo” until it has more empirical evidence linking coal ash to their health issues.

All such advocacy efforts and litigation are time-consuming and expensive, and often bear little fruit. Federal environmental regulations bar many of the types of pollution and contamination happening in prisons, but state and federal agencies seem to have little incentive to enforce these laws with regard to prisoners. As McDaniel says: “With respect to prisons, they assume that nobody cares, and for the most part, that’s what it is.”

Kenneth Hartman points to the broader sentiment that condones threats to the health and lives of people in prison. “The problem is, the intersection of environmental justice and mass incarceration runs right into the teeth of prisoners not being considered worthy of justice,” he writes. “If we complain about dirty water, or poor ventilation systems, or inadequate medical care, there is a collective societal shrug: You should have thought about that before you committed crime.”

Hartman emphasizes that, in order to truly confront the environmental injustices playing out inside prisons, a collective shift in mindset is necessary. He writes, “The only real solution to these problems requires two things that aren’t going to happen any time soon: (1) Serious oversight of the prisons by independent folks with real power to hold officials accountable for outcomes, and (2) our society acknowledging that prisoners are fellow human beings who deserve to be treated with respect and compassion based solely on our humanity.”

This collaborative feature by Truthout and Earth Island Journal is supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism. It will be followed by a series of online investigative reports on the environment and mass incarceration.