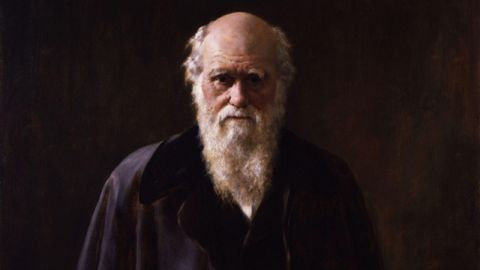

Bill talks with and invites readings by renowned poet, novelist, and editor Philip Appleman, whose creativity spans a long life filled with verse, fiction, philosophy, and religion. The author of nine books of poetry, three novels, and six volumes of non-fiction, Appleman’s most acclaimed work includes explorations of the life and theories of Charles Darwin. A scholar of Darwin, Appleman edited the critical anthology Darwin, and wrote the poetry books Darwin’s Ark and Darwin’s Bestiary, earning him praise for illuminating the “overwhelming sanity” of Darwin’s thought with clarity and wit. Appleman’s latest poetry collection is Perfidious Proverbs.

BILL MOYERS: Faithful viewers of this broadcast know that from time to time we ask poets to drop by and share their work with us. This time, our guest is the versatile Philip Appleman, whose creativity spans a long life filled with verse, fiction, philosophy, science, religion, and above all, moments of every day experience captured like the glint of the sun sparkling through a crystal glass. Just take a look at a sample of his legacy: Darwin, Apes and Angeles, Darwin’s Ark, In the Twelfth Year of the War, Open Doorways, and this, my favorite: Summer Love and Surf, about the joys and wonders of loving and living. His latest book of poems is Perfidious Proverbs.

A fellow poet said that to watch Philip Appleman “sling words is to be richly regaled.” I quite agree.

Welcome Philip.

PHILIP APPLEMAN : Wonderful to be here, Bill.

BILL MOYERS: I have long thought of poetry as music to be heard best in the voice of the composer. So let's go right to some of your poems.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Good. I love it.

BILL MOYERS: Here's one of my favorites. And I think it's one of your favorites, too, “Eve.” Tell me about that poem.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Twenty years ago, I published a book called Let There Be Light. It was a series of satires on various Biblical stories. And Eve being one of the first came out at the head of the list. And, shall I read it?

BILL MOYERS: Please.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Eve is kind of reflecting on the snake, at first.

Clever he was, so slick he could weave words into sunshine. When he murmured another refrain of that shimmering promise, “You shall be as gods,” something with wings whispered back in my heart, and I crunched the apple—a taste so good I just had to share it with Adam. And all of a sudden we were naked. Oh yes, we were nude before, but now, grabbing for fig leaves, we knew that we knew too much, just as the slippery serpent said—so we crouched all day under the rhododendrons, trembling at something bleak and windswept in our bellies that soon we'd learned to call by its right name: fear.

God was furious with the snake and hacked off his legs, on the spot. And for us it was thorns and thistles, sweat of the brow, dust to dust returning. In that sizzling skyful of spite whirled the whole black storm of the future: the flint knife in Abel's heart, the incest that swelled us into a tribe, a nation, and brought us all like driven lambs, straight to His flood. I blamed it on human nature, even then, when there were only two humans around, and if human nature was a mistake, whose mistake was it? I didn't ask to be cursed with curiosity. I only wanted the apple, and of course, that promise—to be like gods. Maybe we are like gods. Maybe we're all exactly like gods. And maybe that's our really original sin.

BILL MOYERS: The original sin. Hubris, right?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: You've said that's one of your favorites. What makes it a favorite?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: I like the personal tone of Eve, who, you know, doesn’t get to say anything in the Bible, to speak of. And to turn her into a kind of down to earth reinterpretor of that kind of tickles me, that's all.

BILL MOYERS: She finally gets to tell her own story.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Right.

BILL MOYERS: Did you ever wonder about the silence in that story of the first woman, as it says?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Yeah. No woman I know would tolerate it.

BILL MOYERS: Exactly. Here's one that we like, especially. It's one of the five poems of pagans that you did. And this is one of the short ones. Would you read that one? And by the way, tell us what Mammon is, for those who haven't been reading the Bible lately.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Well, Mammon is the love of money and greed and he’s the god of wealth. I call it my Bernie Madoff poem.

BILL MOYERS: Read on.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: O Mammon, Thou who art daily dissed by everyone, yet boast more true disciples than all other gods together, Thou whose eerie sheen gleameth from Corporate Headquarters and Vatican Treasury alike, Thou whose glittering eye impales us in the x-ray vision of plastic surgeons, the golden leer of televangelists, the star-spangled gloat of politicos-- O, Mammom, come down to us in the form of Treasuries, Annuities, & High-Grade Bonds, yield unto us those Benedict Arnold Funds, those Quicksand Convertible Securities, even the wet Judas Kiss of Futures Contracts—for unto the least of these Thy supplicants art Thou welcome in all thy many forms. But when Thou comest to say we’re finally in the gentry-- use the service entry.

BILL MOYERS: Do you ever go back and say, "Oh, that's one of my first children. I mean, I remember-- I've forgotten that kid, but now I realize that it is my poem."

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Yeah, I love reading the early poems as much as the late ones. I brought along a poem which it would be an interruption, sort of, of the thrust here. But--

BILL MOYERS: That's what life is about, a series of constant interruptions, Philip, go ahead.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: The first thing you see in this book is a dedication that's for Margie, who happens to be my wife. We're looking forward to our 62nd anniversary this summer. And the dedication says, "Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in thy sight." But because Margie is home and has had a stroke and is ill, I would like to read a poem for her, if you don't mind.

BILL MOYERS: Please do.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: It's from a book called “Summer Love and Surf,” which came out in 1968. And it's the most beautiful book. It's so beautifully designed that it won the—

BILL MOYERS: Oh it is.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: --design contest for that year. And was written when we were living out in Malibu, in one of those houses that are built on stilts. And it's so far on the beach that at high tide, the ocean is gurgling under your bedroom. And we love it there. And this is a young love poem. And in recent years, I've written poems for our 50th anniversary and our 60th anniversary, which are very old love poems. But this is sort of back at the beginning.

“Summer Love and Surf”

Morning was hesitating when you swam at me through wave on wave of sheet and blanket, glowing like some dimly sighted flora at the bottom of the sea. Around your filmy hair, light was seeping in with water sounds, low growling in the distance, like dragons chained.

After our small storm dwindled, we faced the rage outside, swells humping up and charging in to curl and pause and dash themselves to soapsuds on the stork-legged pilings of our house. The roar was hoarser now, The wrecks of kelp were heaping food for flies, our long-nosed sand birds staying close to dry land; farther out, pelicans arched their wings in quick surprise and gulls scream urgently. The call was there: we fought the breakers out and rode their fury back, triumphant and again triumphant, till at last, ears stuffed with brine and heads a-spin like aging boxers battered, we flopped face down on hot sand, smelling sun and salt and steaming skin. Your eyes were suddenly all sleep and love, there in the sun, with sea birds calling.

The sky goes metal at the end, water, gray and hostile, lashing out between the day and night. Plastic swans are threatened; deck chairs, yellow towels, barbecues stand naked to the peril, as if it were winter come by stealth. Still later, in the lee of dark and warmth, we probe the ancient fear: at night the sea is safer under glass, the crude, wild thing half tamed to shed its past— galleons sent to fifty fathoms, mountains hacked to rubble, cities stripped. At night, the sea, barbaric bellows stifled, sprawls outside the window, framed like a dark, unruly landscape. Behind us is a darker kind of dark: I watch your eyes for signals.

The music makes a pause for prophecy: “Tomorrow, off-shore breezes and…” Warmth to each other's warmth, we do not listen.

BILL MOYERS: That was how long ago?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: 1968.

BILL MOYERS: You had been married--

PHILIP APPLEMAN: We had been married 18 years, at that point.

BILL MOYERS: How does love change from then to now?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: It's more profound and more essential. It was very strong right from the beginning. We met on the first day of French class at Northwestern University in 1946. And we've been together ever since.

BILL MOYERS: She became a playwright, didn't she?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: She was a playwright. And her plays have been produced about 60 times in mostly New York and Los Angeles.

And I appreciate her work on my poetry and other things I write. She is a wonderful critic. Four years ago, she had a stroke. And that kind of put an end to her writing. So that was a very sad thrust.

BILL MOYERS: I’m curious as to this poem, “This Year's Valentine.” Where did that come from? What's it about?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: I wrote this right after the Twin Towers went down. This was a poem I wrote for the next Valentine's Day.

They could pump frenzy into air ducts and rage into reservoirs, dynamite dams and drown the cities, cry fire in theaters as the victims are burning, but I will find my way through blackened streets and kneel down at your side. They could jump a median, head-on, and obliterate the future, fit .45's to the hands of kids and skate them off to school, flip live butts into tinderbox forests and hellfire half the heavens, but in the rubble of smoking cottages I will hold you in my arms.

They could send kidnappers to kindergartens and pedophiles to playgrounds, wrap themselves in Old Glory and gut the Bill of Rights, pound at the door with holy screed and put an end to reason, but I will cut through their curtains of cunning and find you somewhere in moonlight.

Whatever they do with their anthrax or chainsaws, however they strip-search or brainwash or blackmail, they cannot prevent me from sending you robins, all of them singing: I'll be there.

BILL MOYERS: A year after 9/11 in that huge climate of fear, how could you have such faith in love?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: It's always been there for me. And it keeps me consciously aware that I'm not alone on this earth yet. We're up in our eighties now, so there'll be a time in sometime soon when I will be alone. But while I'm here the thing that I most value is that, love.

BILL MOYERS: Is that the source of the meaning in your life? I mean, you have this remarkable essay, that had a profound impact on me a few years ago, on how the meaning of life comes out of the moment you're acting, out of your choices every moment, of how you will live that life. "Meaning is not out there," you say, "it is in the doing of the moment."

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Right you create your own definition, you create your own meaning, as you act. I was brought up in a small Indiana town, went to a fundamentalist church. And when I was about 13, thought my mission was to be a missionary to darkest Africa and bring the message. That cleared away a couple of years later. But--

BILL MOYERS: Why did it clear away?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: I kept reading books and finding out things. And after a while, I realized that what I believed in didn't have much to do with reality. And I studied Catholicism for a while. And I went on to take on all the other belief systems. I read all the holy books of, you know, the Koran and the Buddhist and the Hindus.

And I spent years doing that, searching for the meaning of life out there, you know. And eventually, having gone through it all, decided I had to decide on these things for myself. And so I left the holy books behind and started making my own philosophy of life, which pretty much is in the essay you were talking about.

I consider myself a humanist, not just an atheist, but a humanist.

BILL MOYERS: Which means?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Means someone who wishes he could work for the betterment of the human condition without reference to a supernatural thing.

BILL MOYERS: Well, you do often, in your poems. I think of another poem that also has been a favorite of mine, called simply, “Gertrude.” Would you tell me about this one and read it?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: My mother was one of those saintly mothers, some of us are lucky enough to have. Her name was Gertrude. And she was struck by rheumatoid arthritis when she was about 40. And spent a great part of her life after that in bed or in a wheelchair or something. She was hit very hard. And all of her children, my three sisters and I, did everything we could to help, but nothing worked.

And finally she died at the age of 75. I wish that all the people who peddle God could watch my mother die: could see the skin and gristle weighing in at seventy-nine, every stubborn pound of flesh a small death.

I wish the people who peddled God could see her young, lovely in gardens and beautiful in kitchens, and could watch the hand of God slowly twisting her knees and fingers till they gnarled and knotted, settling in for thirty years of pain.

I wish the people who peddle God could see the lightning of His cancer striking her, that small frame tensing at every shock, her sweet contralto scratchy with the Lord's infection: Philip, I want to die.

I wish I had them gathered round, those preachers, popes, rabbis, imams, priests—every pious shill on God's payroll—and I would pull the sheets from my mother's brittle body, and they would fall on their knees at her bedside to be forgiven all their faith.

BILL MOYERS: That's very powerful. And in contrast to all of the people both of us know, some of them who find faith a consolation at the time of death. That's intriguing how the human beings walk such different paths, when it comes to religion.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: When Margie's mother died-- she was another saint. But she died regretting to herself all the sins she had had in her life. And because she hadn't really had any sins, but little shortcomings, she forgot to say thank you to someone or something like that. And the whole thing came crashing in on her and she was convinced she was going to go to hell.

BILL MOYERS: This one is from “Karma, Dharma, Pudding and Pie.” Will you read that?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: This poem has an epigraph from Job. It says, "God will laugh at the trial of the innocent." The poem is called “God's Grandeur.”

When they hunger and thirst, and I send down a famine, When they pray for the sun, and I drown them with rain, And they beg me for reasons, my only reply is: I never apologize, never explain.

When the Angel of Death is a black wind around them And children are dying in terrible pain, Then they burn little candles in churches, but still I never apologize, never explain.

When the Christians kill Jews, and Jews kill the Muslims, And Muslims kill writers they think are profane, They clamor for peace or for reasons at least, But I never apologize, never explain.

When they wail about murder and torture and rape, And unlucky Abel complains about Cain, And they ask me just why I had planned it like this, I never apologize, never explain. Of course, if they're smart they can figure it out-- The best of all reasons is perfectly plain. It's because I just happen to like it this way-- So I never apologize, never explain.

BILL MOYERS: Job kept asking why--

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Poor thing, yeah.

BILL MOYERS: --and never got an answer.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: No.

BILL MOYERS: Jesus himself, "Oh God, why hast thou forsaken me?" No answer.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: I'm not so impervious to the world that I don't know that religion does a lot of good sometimes. That some religious people really are good and they want to do good. But unfortunately, so many religious people let the religions lead them into hatred.

BILL MOYERS: Let's have a little fun with one from “Perfidious Proverbs.” It's actually called “Parable of the Perfidious Proverbs”. And proverb, as people I hope know, is an epigram of wisdom contained in the “Book of Proverbs” in the-- in what Christians call The Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Okay, yeah.

BILL MOYERS: How better it is to get wisdom than gold.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Money buys prophets and teachers, poems and art, So listen, if you're so rich, why aren't you smart?

BILL MOYERS: He that spareth his rod, hateth his son.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: That line gives you a perfect way of testing your inner feelings about child molesting.

BILL MOYERS: He that maketh haste to be rich shall not be innocent.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: But here at the parish, we don't find it overly hard To accept his dirty cash or credit card.

BILL MOYERS: Hope deferred maketh the heart sick.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: That's just why the good Lord made it mandatory To eat your heart out down in Purgatory.

BILL MOYERS: Wisdom is better than rubies.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Among the jeweled bishops and other boobies It's also a whole lot rarer than rubies.

BILL MOYERS: He that trusteth in his own heart is a fool.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Trusting your heart my not be awfully bright, but trusting proverbs is an idiot's delight.

BILL MOYERS: I like that. I like that. That's from “Perfidious Proverbs,” which is your new book. What gives you happiness? What gives you joy?

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Poetry does, music does, theater does, but mostly I think it's just having my wife and living quietly and enjoying being together. I think that's the greatest thing in my life.

BILL MOYERS: Philip Appleman, thank you very much for being with me.

PHILIP APPLEMAN: Thank you.

The Labyrinth

The Labyrinth