BILL MOYERS:

On this inaugural weekend of Barack Obama’s second term, I’ve asked the poet Martín Espada to share with us a moment of revelation that he experienced four years ago, just a few days after Obama was elected as our first African-American president. You need to know that Martín Espada grew up in the tough, ethnically diverse neighborhood of East New York, Brooklyn for you out-of-towners. But when his family moved and became the only Puerto Ricans in a Long Island suburb, he encountered racism head-on. He went to law school and became an advocate for tenants’ rights in Boston where he began to scratch poems on yellow legal pads while waiting in courthouses for cases to be called.

You can’t read any of his 16 books of poems, translations, and essays, including, most recently, The Trouble Ball, without discovering a man who understands life as struggle. A writer for whom the past is a living, breathing muse whispering over his shoulder, as he scribbles, the names of ancestors who once pulled the oars to get us through troubled waters. So it was, four years ago, in the wake of Obama’s victory, that the muse guided Martín Espada here to the graveside of the great 19th century abolitionist, the former slave, Frederick Douglass. And from that moment came this poem:

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Litany at the Tomb of Frederick Douglass

Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester, New York

November 7, 2008

This is the longitude and latitude of the impossible;

this is the epicenter of the unthinkable;

this is the crossroads of the unimaginable:

the tomb of Frederick Douglass, three days after the election.

This is a world spinning away from the gravity of centuries,

where the grave of a fugitive slave has become an altar.

This is the tomb of a man born as chattel, who taught himself to read in secret,

scraping the letters in his name with chalk on wood; now on the anvil-flat stone

a campaign button fills the O in Douglass. The button says: Obama.

This is the tomb of a man in chains, who left his fingerprints

on the slavebreaker’s throat so the whip would never carve his back again;

now a labor union T-shirt drapes itself across the stone, offered up

by a nurse, a janitor, a bus driver. A sticker on the sleeve says: I Voted Today.

This is the tomb of a man who rolled his call to arms off the press,

peering through spectacles at the abolitionist headline; now a newspaper

spreads above his dates of birth and death. The headline says: Obama Wins.

This is the stillness at the heart of the storm that began in the body

of the first slave, dragged aboard the first ship to America.Yellow leaves

descend in waves, and the newspaper flutters on the tomb, like the sails

Douglass saw in the bay, like the eyes of a slave closing to watch himself

escape with the tide. Believers in spirits would see the pages trembling

on the stone and say: look how the slave boy teaches himself to read.

I say a prayer, the first in years: that here we bury what we call the impossible, the unthinkable, the unimaginable, now and forever. Amen.

BILL MOYERS:

How did you come to write that poem?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Well, I happened to be in Rochester, New York doing a reading at a local community college right after the election of Barack Obama. And I discovered to my surprise that Frederick Douglass was buried there. And so I said, "Take me to Frederick Douglass.” And so I went, with one other person and I discovered the tomb in the condition in which it’s described in the poem.

BILL MOYERS:

What did you know about Frederick Douglass that warranted you to go there in the first place?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Frederick Douglass was for me the quintessential American, maybe the greatest American. He was both liberated and liberator. He liberated himself. He went on to liberate others.

BILL MOYERS:

Slaves who were still in bondage.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Exactly. And wrote some of the greatest autobiographies…

BILL MOYERS:

Oh, amazing.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

That this country has ever seen. And so for me this was a matter of pilgrimage, a matter of some urgency. He was a dreamer indeed. And realized his dream. And what is more classically American than that?

BILL MOYERS:

You called him somewhere, "The most complete person of the 19th century, the most complete American of the 19th century."

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yes. Here we have a human condition, slavery, which had been there, present, for thousands of years and had been unquestioned for the most part for thousands of years.

And here was Douglass, imagining the unimaginable, the unthinkable, the impossible. Not only would he liberate himself as he did by escaping, but he would then turn around and liberate others. He would raise the consciousness of the world as he did when he went to Great Britain, he went to Ireland.

Frederick Douglass was brought to Ireland by the temperance movement to speak against slavery. And he spoke in Cork, and people are still talking about it.

BILL MOYERS:

What were you feeling there?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

I was trying to catch lightning in a bottle. I was trying to capture the collective feeling that we shared when we all made history upon the election of the first African-American president. That sense of euphoria, that sense that we had changed the world. That we had made history. Because if we're going to make history, again, we're going to have to recapture that feeling.

BILL MOYERS:

Do you have that feeling this inauguration?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

I still have the same feelings that are expressed in the poem. The poem is independent of the performance of Barack Obama in the White House. It's independent of forces and circumstances that I could not possibly foresee or predict when I wrote the poem. The poem is about transcendence of the historical moment. It was triggered by a very specific historical moment. But it seeks to transcend the historical moment, because this is very much about breaking away from take-it-for-granted realities.

BILL MOYERS:

Take-it-for-granted reality?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yes.

BILL MOYERS:

Which is?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

That the world is as we see it and it always will be. And poets have been saying this for centuries. Poets have been trying to get across this message in one form or another. William Blake, the great English poet wrote in one of his proverbs "What is now proved was once only imagined."

BILL MOYERS:

And of course, they thought of him as a madman, you know that.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Absolutely.

BILL MOYERS:

William Blake.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Absolutely

BILL MOYERS:

What do you take that to mean?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

I take it to mean that all we have to do is look at history to see that things change. And we cannot possibly imagine at the moment of our existence how they will change. We have to have a certain kind of faith. It's paradoxical. But I do believe that even though much of what we do politically is based on what we call facts and what we call evidence, there also has to be an element of faith, whether that faith is in a divine being or not. I don't share that particular kind of faith. But I do have a faith in history.

BILL MOYERS:

Faith in history?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

History. And when we look at the tomb of Frederick Douglass as an altar, decorated as it was that day, we can see the symbolism being played out of that faith in history. This is the tomb of a man who was a slave. He could not vote, he could not belong to a labor union, and forget about the abolition of slavery. That was a taken-for-granted reality in the world into which Frederick Douglass was born in 1818. And look what happened. And now there is an African American president. And that is I'm not making a crude comparison between the abolition of slavery and election of an African American president. I am saying that this is a measure of change. It is a measure of progress. And for those of us who are perversely comforted by the idea that change never happens, I would point to this.

BILL MOYERS:

You talk in the poem about this tomb in Rochester being the longitude and latitude. Talk a little bit about that.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Well, I felt that I was standing at the very physical place where history was breaking through the ground. I refer in another poem, walking through the world, soaking up the ghosts through the soles of my feet. And I felt at that moment that this is what was happening. And, you know, it wasn't even an earthquake, it wasn't like that.

It was the polar opposite of that sensation. It was an unearthly quiet. And I could hear nothing but those leaves falling from the trees with the gentlest breeze. And I had the strange sensation, "Why don't we see 10,000 people here? Why aren't we all here gathered at the tomb of Frederick Douglass to say 'yes' and to say 'thank you?'"

And it was me, and the person who brought me there at the longitude and latitude, right? And standing before the grave of this slave who changed history, and made the history of the present day possible. Without Douglass, there is no Obama.

BILL MOYERS:

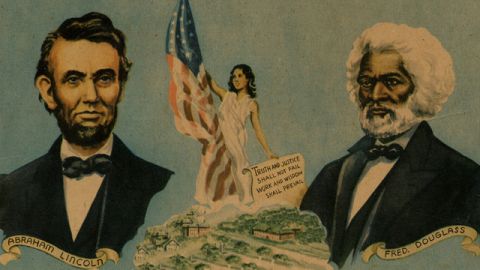

Without Lincoln, there is no Obama. So it's not only a matter, is it, of faith in history, it's a matter of faith in people who have the imagination and the audacity to make history.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Absolutely. And certainly Frederick Douglass understood his role in terms of acting as an advocate during Lincoln's administration. He was obviously putting some pressure on the White House. At the same time, he was issuing a call to arms to his own community to rise up because he understood that history ultimately comes from below. It is it's, you know, it is part of he's enveloping Lincoln in a movement. There's a movement that surrounds Lincoln and the other abolitionists to move all of this forward and make it a reality.

BILL MOYERS:

There weren't 10,000 people with you there at the tomb, but the poem suggests someone else had been there and left this newspaper?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

There were other people who had come before me and had left various objects. I don't know who they were. Someone had left a newspaper. Perhaps aware, perhaps not that Douglass himself had been a journalist, that Douglass himself had been an editor. That Douglass himself would have appreciated a newspaper left at his tomb. Someone else had left a labor union T-shirt. And I found that particularly extraordinary.

BILL MOYERS:

What did it say?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Well, it was, it was from the service workers union. And it was that sticker on the sleeve that said, "I voted today." Remember those were being passed out?

BILL MOYERS:

The S.E.I.U.?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yes.

BILL MOYERS:

Yeah.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Exactly.

BILL MOYERS:

Yes.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

And that's when I began to envision, "Who has left this behind? Someone who's a member of this union. Who were they communicating with? Was it Douglass they were tempting to say to him, 'Look what happened a few days ago.' Were they communicating with me, knowing that someone else would come across these objects?" I don't know.

BILL MOYERS:

You're not going mystical on us, are you?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Maybe. I hope not. Yes. Definitely.

BILL MOYERS:

What do you take that question to mean?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

I take that question to mean that there are times when poets have to go to places that cannot be explained away as a matter of evidence and logic. That we have to be able to reach out and put our hands on the intangible, to touch it, to feel it to see it.

BILL MOYERS:

Martín, where do you think this language of the impossible, the unimaginable comes from?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

For me, it comes from poetry. And it comes from the tradition, the poetic tradition to which I belong. It comes from Walt Whitman. It comes from Pablo Neruda. And it comes from some of my contemporaries as well.

BILL MOYERS:

And what is it? What is happening in that poetry?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

What is happening in that poetry is we are breaking through the boundaries of what we accept as a given every single day. And we see something else as possible. It is an act of the imagination. And too rarely people see the connection between the imagination and the political. There is such a thing as the political imagination.

BILL MOYERS:

Yes.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

You know, and oftentimes those of us who speak in the language of the impossible or the unthinkable, the unimaginable, are called idealists or dreamers or mad, hello William Blake. But we're also pragmatists. We also understand the real world. We also understand the need for visions of a better world because the alternative is despair. And despair is dangerous.

BILL MOYERS:

Anybody who talks the way you talk in politics would be dismissed as utopian.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yes.

BILL MOYERS:

Marginalized. And as sometimes poets are.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yeah.

BILL MOYERS:

Right?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yes.

BILL MOYERS:

Why do you suppose that is? Is it because more practical people simply can't see the dot on the horizon that you see?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

We associate utopia with science fiction, showing those visions gone wrong. We associate utopia with how we perceive communism especially Soviet communism.

Because utopia has been so discredited, so dragged through the mud politically, especially during the years of the Cold War that anyone who speaks in that language is dismissed in one form or another.

BILL MOYERS:

Would you call Frederick Douglass utopian? Barack Obama utopian?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Well, Frederick Douglass, I imagine was like the other abolitionists, regarded as dabbling in dreams.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

And would have been dismissed as a dreamer, or worse, a fraud. Because when his first autobiography came out, when The Narrative came out, many people questioned whether he had written it himself. It was impossible that a slave could have written these words. It must have been one of his abolitionist friends, one of his white abolitionist friends. It must have been Garrison, et cetera. Well, it turns out that indeed, Douglass wrote those words.

BILL MOYERS:

Do you feel the same way four years later about that moment in Rochester?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yes. Absolutely.

BILL MOYERS:

Do you feel the same way about Obama?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

I did not have very high expectations for Obama. He is a politician. He is a pragmatist. He does what he has to do. I have my own criticisms of Obama, having to do with Guantanamo especially.

The drones, there are other issues I could cite. But fair is fair. He also gave us a Puerto Rican Supreme Court Justice, Sonia Sotomayor. And I say that with some pride. I'm Puerto Rican. I also say that in the knowledge that Puerto Ricans are almost entirely excluded from the public conversation in this country, almost completely. And so that is not merely a symbolic gesture. There is something substantial there.

And let's not forget, as long as we're talking about the last four years, the almost fanatical degree of obstructionism perpetrated by the Republican Party as this president attempted to negotiate and negotiate and negotiate and over again, he was rebuffed by this zealotry that has taken over the Republican party. This is not the Republican Party of Frederick Douglass anymore.

BILL MOYERS:

No. Or Lincoln.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Or Lincoln, for that matter.

BILL MOYERS:

Your concern for the concrete realities of struggle and of people who are poor, of the working folks in both Puerto Rico and this country, you know, brings me back to the political reality of the performance of the president. Are working people better off because of this first African American president? Are the poor people you used to represent better off? The Latino farmhands breathing pesticides all those kids trying to learn in overcrowded classes with overworked teachers. Has that election four years ago made a difference to them?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

I will say this that in terms of economics, in terms of everyday realities, I cannot say with any certainty, that people are better off now than they were four years ago. I will say this, that the poem I wrote, which you just heard, is about a vision of something different, something better, the unthinkable, the impossible, the unimaginable. Without the vision, and I think this is something that goes beyond the poet, without the vision, comes despair. With despair comes self-loathing. With self-loathing comes self-destruction, drug abuse, domestic violence, other forms of crime.

The essence of gang warfare, according to Luis Rodriguez and others who have worked with gangs, is the destruction of the mirror image. You cannot lash out at the one who is truly causing you pain and grief. So you lash out at those who are closest to you and those who look just like you. Having a vision of another world is a barrier to that. Frederick Douglass did much more than lobby for the election of Abraham Lincoln. Frederick Douglass was tireless. Frederick Douglass was working as a journalist, he was lecturing, he was agitating, he was knocking on the door of the White House whether the White House wanted him to come in or not.

He did not see social change as beginning and ending with the election of Abraham Lincoln. So why should we see social change as beginning or ending with the election of Barack Obama? Howard Zinn, my beloved friend who died three years ago, January…

BILL MOYERS:

Historian, agitator.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Historian, writer, lecturer, activist, agitator endorsed Obama in 2008 very cautiously saying, "He will have to be enveloped in a social movement, "We have to push him in the right direction." And the question I ask is did we? Did we do enough? Or did we put our weapons down and did we then sit back and wait for something to happen? Again, forgetting that the change that we want comes from below. It comes from a movement. It comes from putting pressure on those that have power to do the right thing.

So when people tell me one way or another that what I represent is a utopian vision, I say, bring more poetry into those schools that are failing. Bring more poetry to the prisons where our young people in the Latino community and beyond are being locked up in record numbers. Bring more poetry into the hospitals. Bring more poetry into all the places where poetry is not supposed to go. And bring it in with the understanding of what it can do.

And then little by little, things will happen. I cannot measure the effect of this poem or any poem on the world. The poems can't be quantified in that way. They can't be boxed or labeled or sold in that way. Thank God for it. But, I do believe that poetry can save us.

BILL MOYERS:

You make it clear in your writings and in your poetry that it's one thing to envision change as a poet and another to work for change as a politician, or as you were a lawyer for the poor. You say it takes both kinds to move history.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

I believe, yes, absolutely. We think of social change as a kind of mosaic or a quilt and many parts contributed to that mosaic or quilt and understanding also the social is not linear, that it doesn't simply move in a straight line. There's progress and then we fall back, progress then we fall back. It zigs, it zags, there are figures of eight.

I would also say this, that the notion that the visionary and the pragmatist are two different people is a false notion. And we're setting up a false dichotomy. I spent years as a legal services lawyer. And I was surrounded by other legal services lawyers. And guess what? They were all visionaries too. They believed that justice was possible. And we were surrounded by a notoriously unjust system. And we could not have thrown ourselves into that system day after day, into that machinery without believing that we could change it.

BILL MOYERS:

Did you?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Yes. I think by our very presence, we changed it. And sometimes those changes are changes that happen years later. And that is something else, another element of social change. Who knows how the election of Barack Obama will affect the world in 50 years or 100 years. Who knows how the poetry will change the world in 50 years or 100 years. It is ultimately an act of faith. You throw the poem into the atmosphere, we breathe it in, and we go on.

BILL MOYERS:

So what's next? What's next that is presently unthinkable, unimaginable, and impossible?

MARTÍN ESPADA:

War. And I don't say that in terms of the complete and utter abolition of war. I say that in terms of changing the military mentality which still infects this culture and the body politic. I think about the fact that as we debate budgets yet again, and I'll say parenthetically, I am here as a poet, not an economist. If there's a fiscal cliff, then I am a fiscal lemming, okay?

But there must be a way that we change that mindset. You know, as we scramble around trying to find dollars for basic human needs, let's start looking at the military and let's start looking at waging war in a different way so that we begin moving in the opposite direction. And maybe it takes a hundred years. But it can be done.

BILL MOYERS:

So with this discussion as our new context, would you read Litany at the Tomb of Frederick Douglass.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

This is the longitude and latitude of the impossible;

this is the epicenter of the unthinkable;

this is the crossroads of the unimaginable:

the tomb of Frederick Douglass, three days after the election.

This is a world spinning away from the gravity of centuries,

where the grave of a fugitive slave has become an altar.

This is the tomb of a man born as chattel, who taught himself to read in secret,

scraping the letters in his name with chalk on wood; now on the anvil-flat stone

a campaign button fills the O in Douglass. The button says: Obama.

This is the tomb of a man in chains, who left his fingerprints

on the slavebreaker’s throat so the whip would never carve his back again;

now a labor union T-shirt drapes itself across the stone, offered up

by a nurse, a janitor, a bus driver. A sticker on the sleeve says: I Voted Today.

This is the tomb of a man who rolled his call to arms off the press,

peering through spectacles at the abolitionist headline; now a newspaper

spreads above his dates of birth and death. The headline says: Obama Wins.

This is the stillness at the heart of the storm that began in the body

of the first slave, dragged aboard the first ship to America. Yellow leaves

descend in waves, and the newspaper flutters on the tomb, like the sails

Douglass saw in the bay, like the eyes of a slave closing to watch himself

escape with the tide. Believers in spirits would see the pages trembling

on the stone and say: look how the slave boy teaches himself to read.

I say a prayer, the first in years: that here we bury what we call the impossible, the unthinkable, the unimaginable, now and forever. Amen.

BILL MOYERS:

The book is The Trouble Ball, the poet is Martín Espada. Martín, thank you for being with me.

MARTÍN ESPADA:

Thank you very much.

Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln

Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln