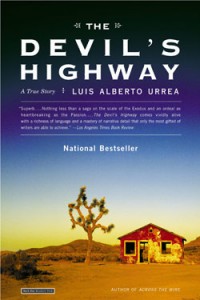

In these excerpts from the first chapter of The Devil’s Highway, Luis Alberto Urrea writes about the Yuma 14, the dangerous and dark history of El Camino del Diablo (or “Highway of the Devil”) and the border patrol agents at Welltown Station.

Five men stumbled out of the mountain pass so sunstruck they didn’t know their own names, couldn’t remember where they’d come from, had forgotten how long they’d been lost. One of them wandered back up a peak. One of them was barefoot. They were burned nearly black, their lips huge and cracking, what paltry drool still available to them spuming from their mouths in a salty foam as they walked. Their eyes were cloudy with dust, almost too dry to blink up a tear. Their hair was hard and stiffened by old sweat, standing in crowns from their scalps, old sweat because their bodies were no longer sweating. They were drunk from having their brains baked in the pan, they were seeing God and devils, and they were dizzy from drinking their own urine,the poisons clogging their systems.

They were beyond rational thought. Visions of home fluttered through their minds. Soft green bushes, waterfalls, children, music. Butterflies the size of your hand. Leaves and beans of coffee plants burning through the morning mist as if lit from within. Rivers. Not like this place where they’d gotten lost. Nothing soft here. This world of spikes and crags was as alien to them as if they’d suddenly awakened on Mars. They had seen cowboys cut open cacti to find water in the movies, but they didn’t know what cactus among the many before them might hold some hope. Men tore their faces open chewing saguaros and prickly pears, leaving gutted plants that looked like animals had torn them apart with their claws. The green here was gray.

They were walking now for water, not salvation. Just a drink. They whispered it to each other as they staggered into parched pools of their own shadows, forever spilling downhill before them: Just one drink, brothers. Water. Cold water! They walked west, though they didn’t know it; they had no concept anymore of destination. The only direction they could manage was through the gap they stumbled across as they cut through the Granite Mountains of southern Arizona. Now canyons and arroyos shuffled them west, toward Yuma, though they didn’t know where Yuma was and wouldn’t have reached it if they did.

They came down out of the screaming sun and broke onto the rough plains of the Cabeza Prieta wilderness, at the south end of the United States Air Force’s Barry Goldwater bombing range, where the sun recommenced its burning. Cutting through this region, and lending its name to the terrible landscape, was the Devil’s Highway, more death, another desert. They were in a vast trickery of sand.

In many ancient religious texts, fallen angels were bound in chains and buried beneath a desert known only as Desolation. This could be the place.

In the distance, deceptive stands of mesquite trees must have looked like oases. Ten trees a quarter mile apart can look like a cool grove from a distance. In the western desert, twenty miles looks like ten. And ten miles can kill. There was still no water; there wasn’t even any shade.

Black ironwood stumps writhed from the ground. Dead for five hundred years, they had already been two thousand years old when they died. It was a forest of eldritch bones. The men had cactus spines in their faces, their hands. There wasn’t enough fluid left in them to bleed. They’d climbed peaks, hoping to find a town, or a river, had seen more landscape, and tumbled down the far side to keep walking. One of them said, “Too many damned rocks.” Pinches piedras, he said. Damned heat. Damned sun.

Now, as they came out of the hills, they faced the plain and the far wall of the Gila Mountains. Mauve and yellow cliffs. A volcanic cone called Raven’s Butte that was dark, as if a rain cloud were hovering over it. It looked as if you could find relief on its perpetually shadowy flanks, but that too was an illusion. Abandoned army tanks, preserved forever in the dry heat, stood in their path, a ghostly arrangement that must have seemed like another bad dream. Their full-sun 110-degree nightmare.

“The Devil’s Highway” is a name that has set out to illuminate one notion: bad medicine.

The first white man known to die in the desert heat here did it on January 18, 1541.

Most assuredly, others had died before. As long as there have been people, there have been deaths in the western desert. When the Devil’s Highway was a faint scratch of desert bighorn hoof marks, and the first hunters ran along it, someone died. But the brown and red men who ran the paths left no record outside of faded songs and rock paintings we still don’t understand.

Desert spirits of a dark and mysterious nature have always traveled these trails. From the beginning, the highway has always lacked grace — those who worship desert gods know them to favor retribution over the tender dove of forgiveness. In Desolation, doves are at the bottom of the food chain. Tohono O’Odham poet Ofelia Zepeda has pointed out that rosaries and Hail Marys don’t work out here. “You need a new kind of prayers,” she says, “to negotiate with this land.”

*****

The men walked onto the end of a dirt road. They couldn’t know it was called the Vidrios Drag. Now they had a choice. Cross the road and stagger along the front range of the mountains, or stay on the road and hope the Border Patrol would find them. The Border Patrol! Their nemesis. They’d walked into hell trying to escape the Border Patrol, and now they were praying to get caught.

In their state, a single idea was too complex, and they looked upon it with uncertainty. They shuffled around. It was ten o’clock in the morning, 104 degrees. Dust devils, dead creosote rattling like diamondbacks, the taunting icy chip of sunlight reflected off a high-flying plane. Weird sounds in the landscape: voices, coughs, laughter, engines. It was the desert haunting they’d been hearing all along. When they heard the engine coming, it sounded like locusts flying overhead, cicadas, wind. And the dust rising could have been smoke from small fires. The flashes of white out there, heading toward them, popping out from behind saguaros and paloverde trees—well, it could have been ghosts, flags, a parade. It could have been anything. They didn’t know if they should hide or stand their ground and face whatever was coming their way.

When the windshield flashed in the morning sun, they stood, they walked, ran, tripped, fell. Toward the truck, the white truck. The unlikely geometry of disaster once again worked them into its eternal ciphers.

Border Patrol agent Mike F., at the tail end of another dull drag, was driving his Explorer at a leisurely pace. No fresh sign anywhere on the ground. Boredom. He was about to pull a U and head back to 25E, the dirt road that cut down from Interstate 8 to the Devil’s Highway and the Mexican border beyond, looked up, and beheld the men as they walked out of the light. Nothing special. You got lost walkers all the time, people begging for a drink. They often gave themselves up when they realized the western desert had gotten the better of them. Sometimes, you beat them down with your baton, and sometimes everybody just laughed and drank your water.

Only one of the walkers stepped forward. The rest hid under trees. They were watching Mike F. like deer in the shadows. He took in the scene as he rolled toward them. He stopped, put the truck in park, and opened his door. He put out a foot and gestured for them with one hand to stay put while he got the radio mike with the other and called in to Wellton Station. Cops tend to assess a situation at first glance — people are always up to something. In the desert, they were often involved in some form of dying. Most of them, if not in trouble, were sneaky.

*****

The five men rushed toward the truck. “They’re dying,” they gasped. “Who’s dying?” “Men. Back there. Amigos.” Seventeen men, they said. Agent F. gave them water. They gulped. They puked the water back out and didn’t care. They drank more. “Muertos! Muertos!”

Seventeen. Then thirty. One man thought there were seventy bodies fallen behind them. When Agent F. called it in to Wellton, the station’s supervisory officer said, “Oh, s—.”

*****

All the agents seem to agree that the worst deaths are the young women and the children. Pregnant women with dying fetuses within them are not uncommon; young mothers have been found dead with infants attached to their breasts, still trying to nurse. A mother staggers into a desert village carrying the limp body of her son; doors are locked in her face. The deaths, however, that fill the agents with deepest rage are the deaths of illegals lured into the wasteland and then abandoned by their Coyotes. When the five dying men told Agent F. they’d been abandoned, he called in the information. The dispatcher responded with a Banzai Run.

The town of Wellton is in a wide plain on I-8. It is tucked between Yuma’s mountain ranges and the Mohawk Valley, with its strange volcanic upthrusts. The American Canal cuts through the area, and a bombing range is to the south. Running just below I-8 is the railway line that carries freight from Texas to California. Most train crews have learned to carry stores of bottled water to drop out of their locomotives at the feet of staggering illegals.

Wellton Station sits atop a small hill north of the freeway. It is isolated enough that some car radios can’t pick up a signal on either AM or FM bands. Cell phones often show “Out of Service Area” messages and go mute.

Many agents, borderwide, commute a fair distance to their stations. Drives of twenty, forty, even seventy miles are common. But the trips to and from work afford them a period of quiet, of wind-down or wind-up time. It is not always easy to leap from bed and go hunt people. Besides, the old-timers have learned to really love the desert, the colors in the cliffs, the swoop of a red-tailed hawk, the saffron dust devils lurching into the hills.

For most agents, it works this way: you get up at dawn and put on your forest green uniform. As you get to work, you pull in behind the station to the fenced lot. You punch in your code on the keypad, and you park beside the other machines safe from your enemies behind the chain-link. Our station is a small Fort Apache. On one side, the agents line up their trucks and sports cars, and on the other side sits the fleet of impeccably maintained Ford Explorers. Border Patrol agents are often military men, and they are spit-and-polish. Their trucks are clean and new; their uniforms are sharp; and their offices are busy but generally squared away. The holding cells in the main building — black steel mesh to the far left of the main door — sparkle. Part of this is, no doubt, due to the relentless public focus on the agency. In Calexico, the Mexican consulate has upped the ante by placing a consulate office inside the actual station: prisoners are greeted by the astounding sight of a service window with Mexican flags and Mexican government signs.

Inside, Wellton Station is a strange mix of rundown police precinct and high-tech command center. Old wood paneling, weathered tables. Computers and expensive radios at each workstation. In the back building, supervisory officer and mainstay of the station Kenny Smith has a couple of radios going, which he listens to, and a couple of phones ringing every few minutes, which he generally ignores. A framed picture of a human skull lying in the desert hangs on the wall. It has a neat hole in the forehead,above one eye socket. “Don’t get any cute ideas,” one of the boys says. “We didn’t shoot that guy.”

A computer is on all the time, and GPS satellite hardware bleeps beside it. Above Kenny’s desk is a huge topo map showing the region. He sits in a swivel chair and reigns over his domain. He has an arrow with its notched end stuffed into a gas station antenna ball. He holds the ball in his fist and uses the arrow to point out various things of interest on the map.

On the wall is the big call-chart. Names and desert vectors are inked onto a white board in a neat grid. Agents’ last names are linked to their patrol areas. In the morning, you check the board, banter with Kenny, say good morning to the station chief, stop by to say hello to Miss Anne, who runs the whole shebang from her neat desk in the big main room out front.

The town of Wellton is farms and dirt, dirt and farms. New agents, fresh from the East or West coasts, amuse the old boys by asking where they can find an espresso or a latte. Kenny Smith tells them, “Well, you can go down to Circle K and get a sixteen-ounce coffee. Then put some flavored creamer in it.” That one never fails to get a laugh out of the old boys. An agent, sipping his stout coffee, is mid-story: “…And here comes Old José,” he says, “all armed-up on some girlie!” Old José seems to be the archetypal tonk who shows up in stories. The listener, a steroidal-looking Aryan monster with a military haircut and a bass voice, notes: “Brutal.” He turns to his computer keyboard and plugs away with giant fingers.

Everybody speaks Spanish. Several of the agents are Mexican Americans. Quite a few in each sector who aren’t “Hispanic” are married to Mexican women.

Wellton Station is considered a good place to work. The old boys there are plain-spoken and politically incorrect. INS and Border Patrol ranks are overrun with smooth-talking college boys mouthing carefully worded sound bites. Not so in Wellton. Agents will tell you that the only way to get a clear picture of the real border world is to find someone who has been in service over four years. A ten-year veteran is even better. Wellton has its share of such veterans, but any agent who has been in service for ten years knows better than to talk to you about his business. A great compliment in the Border Patrol is: “He’s a good guy.” Wellton’s agents are universally acknowledged by other agents as good guys. Jerome Wofford, they say, will give you the shirt off his back; the station chief will lend you his cherry SUV if you have special business.

Like the other old boys of Wellton Station, you love your country, you love your job, and though you would never admit it, you love your fellow officers. Civilians? They’ll just call you jack-booted thugs, say you’re doing a bad job, confuse you with INS border guards. You’re not a border guard, you’re a beat cop. Your station chief urges you not to hang out in small-town restaurants, not to frequent bars. Don’t go out in uniform. Don’t cross the border. Don’t flash your badge. Don’t speed, and if you do and get tagged for a ticket, don’t use your badge to try to get out of it. Don’t talk to strangers. In hamlets like Naco, San Luis, Nogales, civilians often won’t make eye contact. Chicanos don’t like you. Liberals don’t like you. Conservatives mock and insult you. And politicians…politicians are the enemy.

There’s always someone working in the office, early or late, every day and every night of every year. They’re guarding the cells, monitoring the radios, writing reports. Sometimes, you can’t sleep you can always come in to the clubhouse and find someone to talk to. Somebody who votes like you, talks like you. Believes in Christ or the Raiders like you. You can make coffee for the illegals in the cage, flirt with the senoritas — though with all the sexual assault and rape charges that dog the entire border, you probably don’t. Human rights groups are constantly lodging complaints, so you watch yourself. The tonks supposedly have phones in their holding pens so they can call lawyers to come slaughter you if you do anything wicked. You pull up one of the rolling office chairs, turn your back to them, and sit at a radio and listen to the ghostly voices of your partners out in the desert night, another American evening passing by.

******

It was the big die-off, the largest death-event in border history.

Everybody wanted to know what happened, how it happened. The old boys of Wellton were forever changed by it. The media started calling the dead the Yuma 14. National stories focused on the Devil’s Highway as a great metaphor for the horrors of the trail. But the agents who saw it all simply refer to it as “what happened.” As in: what happened in May, or what happened in the desert. Nothing fancy.

Somebody had to follow the tracks. They told the story. They went down into Mexico, back in time, and ahead into pauper’s graves. Before the Yuma 14, there were the smugglers. Before the smugglers, there was the Border Patrol. Before the Border Patrol, there was the border conflict. Before them all was Desolation itself.

These are the things they carried.

John Doe #36: red underpants,mesquite beans stuck to his skin.

John Doe #37: no effects.

John Doe #38: green socks.

John Doe #39: a belt buckle with a fighting cock inlaid, one wallet in the right front pocket of his jeans.

John Doe #40: no effects.

John Doe #41: fake silver watch, six Mexican coins, one comb, a belt buckle with a spur inlaid, four pills in a foil strip — possibly Advil, or allergy gelcaps.

John Doe #42: Furor Jeans, “had a colored piece of paper” in pocket.

John Doe #43: green handkerchief, pocket mirror in right front pocket.

John Doe #44: Mexican bills in back pocket, a letter in right front pocket, a brown wallet in left front pocket.

John Doe #45: no record.

John Doe #46: no record.

John Doe #47: no effects; one tattoo: “Maria.”

John Doe #48: Converse knockoff basketball shoes.

John Doe #49: a photo ID of some sort, apparently illegible.

They came to the broken place of the world, and taken all together, they did not have enough items to fill a carry-on bag.

*****

The reports arrive from the officials, so many that it’s getting hard to file them. Shelves are stuffed with them, and piles of reports sometimes accumulate on the tabletops. The Yuma 14’s documents, like all of the death reports at the consulate, were tucked into accordion folders, cheap manila packets available in any Target or Kmart. The death packets are known as “archives,” and harvest season — May through July — is known as “death season.”

It is then that lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers, oranges, strawberries are all ready to be picked. Arkansas chickens are ready to be plucked. Cows are waiting in Iowa and Nebraska to be ground into hamburger, and grills are ready in McDonald’s and Burger King and Wendy’s and Taco Bell for the ground meat to be cooked. KFC is waiting for its Mexican-plucked, Mexican-slaughtered chickens to be fried by Mexicans. And the western desert is waiting, too — its temperatures soaring, a fryer in its own right.

*****

Of course, the illegals have always been called names other than human — wetback, taco-bender. (A Mexican worker said: “If I am a wetback because I crossed a river to get here, what are you, who crossed an entire ocean?”) In politically correct times, “illegal alien” was deemed gauche, so “undocumented worker” came into favor. Now, however, the term preferred by the Arizona press is “undocumented entrant.” As if the United States were a militarized beauty pageant. Maybe it is.

In the strange military poetics of the Border Patrol, the big kill itself is known not only as the Case of the Yuma 14. It is officially called “Operation Broken Promise.” Of all the catch phrases of the event, this is perhaps the most accurate.

Copyright © 2004 by Luis Urrea