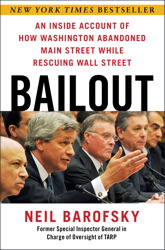

Bill recently interviewed Neil Barofsky, the Treasury Department Inspector General appointed to oversee TARP, on Moyers & Company. His book, Bailout: An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street, was published in July 2012.

In this excerpt, Barofsky explains the problems he saw with the Home Affordable Modification Program. HAMP — implemented in March 2009 as part of the Making Homes Affordable Program — was a loan modification program designed to reduce monthly payments for homeowners who were delinquent or at risk for delinquency in repaying their mortgages. Participants were required to remit the estimated new monthly payments during a “trial period” before the modifications would become permanent.

The flood of trial modifications caused the servicers’ systems to first buckle and then break as borrowers seeking to make their modifications permanent flooded the underequipped servicers with millions of pages of documents. The servicers’ performance was abysmal: they routinely “lost” or misplaced borrowers’ documents, with one servicer telling us that a subcontractor had lost an entire trove of HAMP materials. Borrowers routinely complained that they’d had to send their documents to their servicers multiple times — a survey by ProPublica found that borrowers had to submit documents on average six times — but the servicers would still claim that the documents had never been received and then foreclose. The sheer volume also meant that fully qualified borrowers got lost in the storm; servicers would later confess to us that the sheer volume from Treasury’s verbal trial modification surge made it nearly impossible for them to separate the modifications that fully qualified and had a chance to be successful from those that were hopeless.

The flood of trial modifications caused the servicers’ systems to first buckle and then break as borrowers seeking to make their modifications permanent flooded the underequipped servicers with millions of pages of documents. The servicers’ performance was abysmal: they routinely “lost” or misplaced borrowers’ documents, with one servicer telling us that a subcontractor had lost an entire trove of HAMP materials. Borrowers routinely complained that they’d had to send their documents to their servicers multiple times — a survey by ProPublica found that borrowers had to submit documents on average six times — but the servicers would still claim that the documents had never been received and then foreclose. The sheer volume also meant that fully qualified borrowers got lost in the storm; servicers would later confess to us that the sheer volume from Treasury’s verbal trial modification surge made it nearly impossible for them to separate the modifications that fully qualified and had a chance to be successful from those that were hopeless.

Aggravating the problem was that the design of the program potentially rewarded servicers who “lost” documents: It could be more profitable for a servicer to drag out trial modifications and eventually foreclose than to award the borrowers quick permanent modifications. Mortgage servicers earn profits from fees, particularly late fees, and under HAMP, Treasury allowed mortgage servicers to charge and accrue late fees for each month that borrowers were in trial modifications, even if the borrowers made every single payment under their trial plans. (The rationale was that by not making the full unmodified payment, the borrowers were technically “late” on each payment.) If the modifications were made permanent, Treasury required the servicer to waive the fees, but if the servicer canceled the modifications (say, for example, for the borrowers’ alleged failure to provide the necessary documents), the servicer could typically collect all of the accrued late fees once the homes were sold through foreclosure. In other words, servicers could rack up fees by putting home owners into late fee–generating trial modification purgatory and then pulling the rug out from under them by failing their modification for “incomplete documentation,” which they did in droves. Indeed, even though Treasury eventually changed its practice of allowing undocumented trial modifications, by early 2012 there were still more HAMP modification failures than successes.

As a further incentive for bad behavior, Treasury gave the servicers permission to take all the preliminary legal steps necessary to foreclose at the exact same time that they were supposedly processing the trial modifications. Though servicers technically weren’t supposed to actually foreclose while a trial modification was pending, they reportedly were doing so anyway. Servicers were also apparently demanding up-front payments before putting borrowers into modifications and requiring them to waive all claims and defenses before considering them for one, both blatant violations of program rules.

The abuses didn’t stop there, though. One particularly pernicious type of abuse was that servicers would direct borrowers who were current on their mortgages to start skipping payments, telling them that that would allow them to qualify for a HAMP modification. The servicers thereby racked up more late fees, and meanwhile many of these borrowers might have been entitled to participate in HAMP even if they had never missed a payment. Those led to some of the most heartbreaking cases. Home owners who might have been able to ride out the crisis instead ended up in long trial modifications, after which the servicers would deny them a permanent modification and then send them an enormous “deficiency” bill. They were charged for the difference between the modified monthly payments and the original amount of their payments for all of those months, which could be a crippling amount, and were also slapped with a host of late fees. Borrowers who might otherwise never have missed a payment found themselves hit with whopping bills that they couldn’t pay and now faced foreclosure. It was a disaster.

Making matters even worse, Treasury all but paved the way for outright fraud by ignoring my recommendation that it kick off HAMP with a broad nationwide television and radio advertising campaign that would educate home owners about program details and warn them of the dangers of program-related fraud. I had begged Treasury to at least run public service announcements in the cities that had seen the highest incidents of fraud in the run-up to the financial crisis, warning that dormant mortgage fraud cells would soon reemerge. They failed to do so, and, as I had predicted, the chaos of HAMP lured a host of criminal predators running fraudulent advertisements for “guaranteed Obama modifications” from coast to coast.

Another case took me back to New York to announce charges against the principals of American Home recovery, which operated a similar scheme in which they were accused with not only charging up-front fees but also telling borrowers to forward to them, instead of to the banks, partial “mortgage payments,” which they then pocketed. We helped obtain similar charges in cases around the country.

Our investigation team worked tirelessly, building those cases and working with other agencies to shut down as many of the scams as we could, but it was a game of whack-a-mole that we could never win. A broad early public awareness campaign was the only thing that would have given us a chance to combat the fraud, but Treasury didn’t listen about that until it was far too late, not airing its first commercial until the middle of 2010.

Treasury also failed to take action against the servicers themselves. Because most of the abuses we saw coming into our hotline involved accusations that servicers had violated their contracts with Treasury, those fell under Treasury’s jurisdiction and there was little we could do other than refer them to Treasury. We did what we could to get the borrowers the help they needed, but ultimately any action against the servicers would have to be brought by Treasury, not us. Treasury, however, demonstrated no interest in taking even the most modest steps to punish them. That was unconscionable, given the pain being inflicted on so many home owners.