One of the primary arguments against allowing big box stores — such as Walmart, Lowe’s, Target and Best Buy — to set up shop in small towns is that they take customers away from local family businesses that have existed in the community for years. Using high-volume sales — versus price mark-ups — to drive profits, big box stores are often able to sell their goods at lower prices. But they also employ fewer workers than their Main Street competition and pay those workers substantially less. The net effect is often slower community economic growth and dying downtowns.

But when big box stores are given permission to build, these long-term financial effects often aren’t considered. Almost all local planning policies limit discussion about big box stores to zoning issues, “like how much traffic the store will generate and whether the site has sufficient landscaping,” Stacy Mitchell, a senior researcher with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, writes in Grist. Discussion of the store’s impact on the economy is rarely on the table.

But Cape Cod, a peninsula in Massachusetts made up of 15 economically diverse towns — some very wealthy, some less so — found a way to have that conversation. In 1988, 76 percent of voters endorsed a ballot initiative that lead to the creation of the Cape Cod Commission, a board made up of representatives from the 15 towns, as well as members representing minority communities in the county. The commission reviews the environmental and economic impact of proposed building projects in the region. It doesn’t replace the city planning boards other towns have, but adds a second layer of review for projects that will have a major impact on the community — including buildings that exceed 10,000 square feet, as nearly all big box stores do. Over the last few years, the commission has vetoed a Wal-Mart, a Sam’s Club, a Costco and a Home Depot that it felt would negatively alter the surrounding communities. The commission has approved other big box stores in the area when the stores agreed to abandon their original plans and open smaller locations in vacant, already-built retail locations.

A number of cities have a similar system, but Mitchell notes that Cape Cod’s model may work better. “One of the advantages of Cape Cod’s approach is that it’s regional,” she writes, “so developers can’t just threaten to move next door if one municipality says no.” Vermont is the only place that mandates this system on the state level — large projects must be reviewed for economic, social and environmental impact by both local governments and by one of nine regional commissions.

This summer, the Cape Cod Commission is considering a proposal for a new Lowe’s to be built in South Dennis. Lowe’s submitted a report to the commission stating that the new store would create 115 jobs. But a local group responded with their own economic impact report and found that the store would take away about 10 to 20 percent of sales from small competing businesses within a 15 minute drive of the store, which, in turn, would lead to 163 full- and part-time workers losing their jobs. At two commission hearings later this month, Cape Cod residents will have a chance to weigh in on the other pros and cons of allowing the Lowe’s to be built.

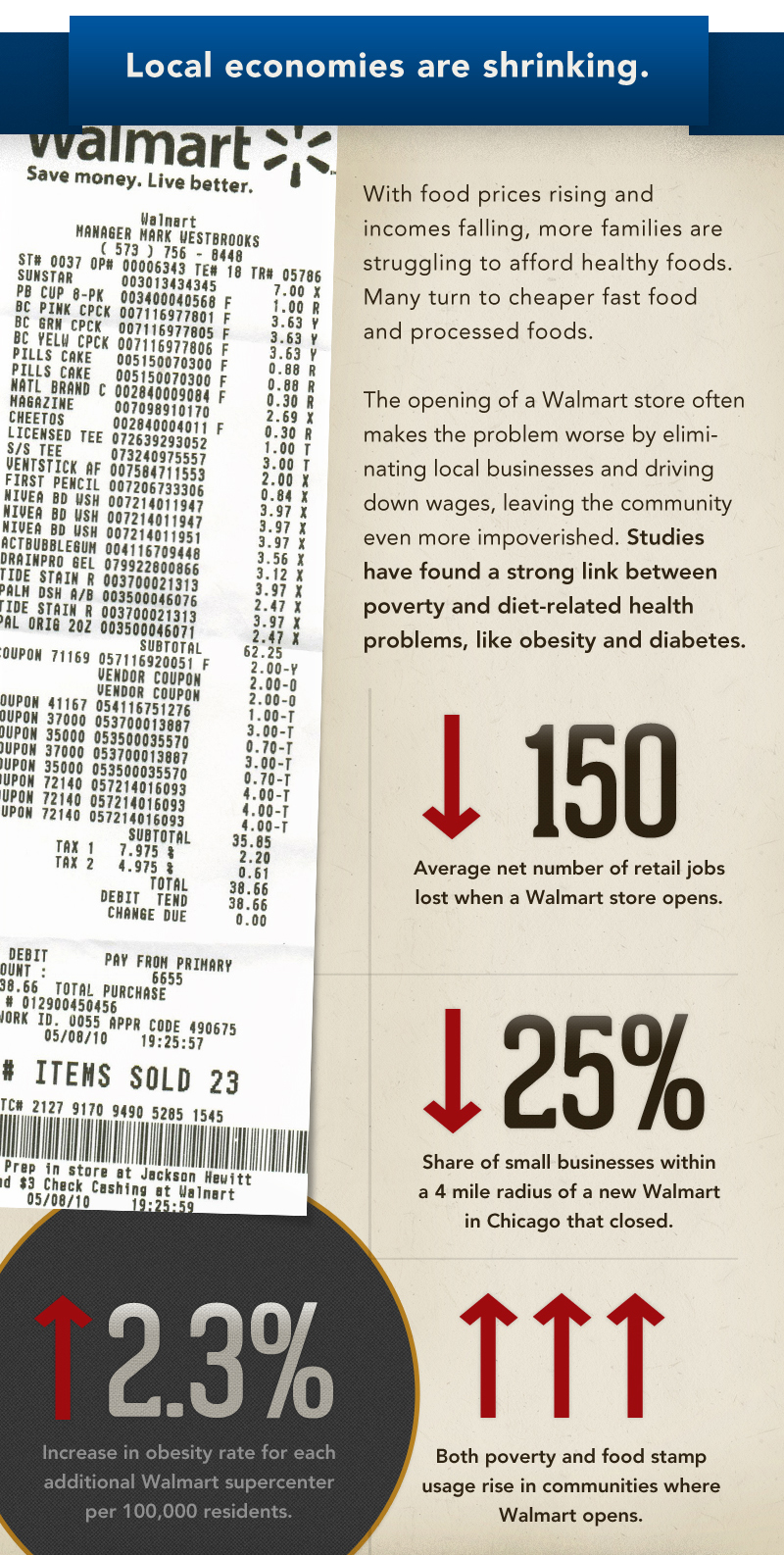

This infographic, published by the Institute for Local Self Reliance, draws on academic research to examine the effects Wal-Mart – — the most successful big box store in history — has had on communities.

Infographic Sources: