It feels like a really strange time, as if we had been hit by a truck and pushed off the road of normality. Looking back over the history of the United States, it is a strange time. There are few precedents for the combination of an epidemic that has taken so many lives and forced profound changes in day-to-day life; a deep economic recession; repeated natural disasters; a massive wave of protest over police violence and racial inequality; repeated use of state force to repress dissent; and a tense, nasty Presidential election. Uncertainty about when – or if – we will return to life as we knew it has added to our anxiety and fueled frightening social and political conflicts. But our current moment is not totally unique. A century ago, during the latter part of World War I and its immediate aftermath, developments similar to those today left Americans wondering if their accustomed way of life might be coming to an end.

Influenza Hospital Ward, 1919 (Library of Congress)

The most obvious analog is the influenza epidemic of 1918-19. Between September 1918 and June 1919, an estimated 675,000 people died of what was commonly called the “Spanish Flu,” the equivalent of 2.1 million deaths for our current population, far above the toll of COVID-19. Like now, neither a cure nor a vaccine was available, only public health measures similar to ones now being deployed: masks; the closing of schools and other public places; and the quarantining of military bases, where the flu had begun its rampage. But oddly, the epidemic seemed to have little impact on politics or the national mood. The New York Times noted in November 1918 that “Perhaps the most notable peculiarity of the influenza epidemic is the fact that it has been attended by no traces of panic or even excitement.” In a society more accustomed to death by contagious disease, living in the shadow of the mass slaughter of war, the flu did not have the same destabilizing effect as Coronavirus.

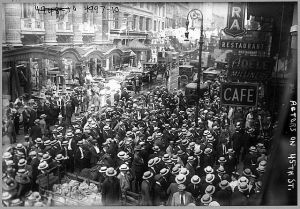

Actors’ strike, New York, New York, 1919. (LOC)

But the wave of strikes and demonstrations that overlapped with the flu epidemic had even greater political and social impact than the extraordinary eruption of protest that followed the killing of George Floyd. In 1919, one out of every five wage earners went out on strike, a level never since matched, including everyone from Seattle shipbuilders to Boston policemen and New York actors to Pennsylvania steel workers. Coming amid surging global left-wing enthusiasm, sparked by the Russian Revolution, the labor mobilization appeared to business and political leaders as an existential threat to the established order. So did the sense of empowerment among African Americans who had gone to Europe in the Army or moved to northern cities to take newly available jobs in industry.

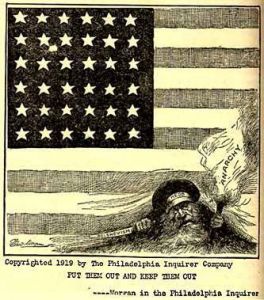

State repression and vigilante violence largely succeeded in checking the forces of change. Police, National Guard, and private thugs were used to break strikes, as employers and their allies equated labor militancy with disloyalty and foreign-led radicalism. Congress and state legislatures passed criminal syndicalism laws and other measures designed to undermine labor and the left. In Washington, D.C., Omaha, Chicago, and rural Arkansas, whites attacked African Americans in deadly incidents dubbed race riots but actually more like pogroms.

As the 1920 election approached, the Woodrow Wilson administration brought the “Red Scare” to new heights with mass arrests of labor activists, socialists, and anarchists and the deportation of the foreign-born among them (including, most famously, Emma Goldman). Sometimes democratic norms were simply chucked aside, as when the House of Representatives refused to seat Victor Berger, the duly-elected Socialist Party representative from Milwaukee, and the New York State Assembly expelled five Socialist assemblymen.

Red Scare Cartoon, 1919.

Put Them Out And Keep Them Out –Anarchy

By the time President Warren G. Harding was inaugurated in March 1921, after running on a call for “not nostrums but normalcy, not revolution but restoration,” the labor and left tides had already had begun to recede. Seeking to lower social tensions, Harding not only pardoned Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, who had been jailed for opposing World War I, but also insisted he stop by the White House for a chat. For nearly a decade, conservative Republican administrations managed to preside over a business-dominated economy and growing inequality without serious social disruption, until the Great Depression brought it all crashing down.

Returning to normalcy may prove more difficult this time around. If Donald Trump wins reelection, it seems likely that social conflict, repression, and deviations from democratic norms will continue, with the scary trend toward vigilantism perhaps accelerating. Joe Biden might do better; at least he will try to lower tensions rather than provoke them. But even if he could restore the country to pre-COVID conditions, the economic inequality and racial inequities made more obvious than ever during the pandemic will continue to fuel dissent. And hovering over everything are the devastating effects of climate change, making business as usual social suicide. Getting back to normality may be not only impossible but also a terrible idea.