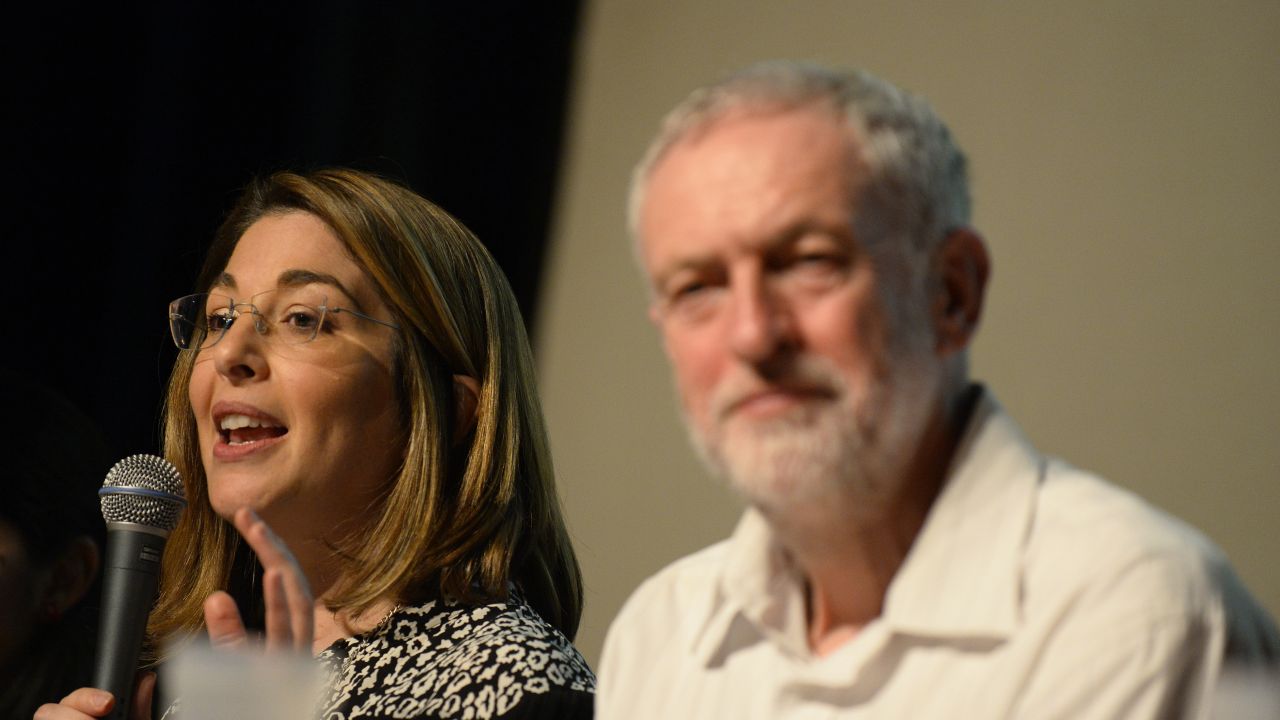

Author and activist Naomi Klein attends a meeting with British Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn during the COP21 climate change conference. (Photo by John van Hasselt/Corbis via Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at In These Times.

By her own admission, Naomi Klein’s books tend to be tomes. In three several-hundred-page doorstoppers, each comprising a half-decade’s worth of research and reporting, she’s explored the damage wrought by cynical corporate branding projects (No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies), the way neoliberal strategists exploit crises for profit (The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism) and the deep connection between the climate crisis and our economic system (This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate). When Trump was elected, Klein decided to take a new tack. Her latest book, No Is Not Enough: Resisting the New Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need, is a good deal shorter, synthesizing lessons from her work over the last 20 years into a theory of how Donald Trump won and how to fight him.

In These Times sat down with Klein in mid-June to talk Corbyn, Trump, climate change, populism and the “hollow branding” and shock-therapy economics that got us here.

In These Times: To start on an upbeat note, the UK Labour Party and its leader, Jeremy Corbyn, have just pulled off a huge upset — in part by campaigning on what, in the United States, would be considered a far-left platform. Is there a lesson here for the US?

Naomi Klein: One of the lessons is that the ideas matter at least as much as the messenger. The messenger does matter, and having political skill matters. But being trustworthy matters, and something Corbyn and Bernie Sanders share is they don’t have a lifelong history of flip-flopping. They’ve had a core set of beliefs for a long time, and they’re not slick. There is something about that un-slickness that is making them trustworthy carriers for these policies.

Once again, we are learning that bold, transformative ideas that really hold up the promise of tangibly improving people’s lives can win elections or come damn close. And so that’s exciting, and it’s a fearsome responsibility: If the left can win, that means the left must win. That’s not a sense of responsibility that I grew up with. We thought we could never run on a platform like this. It turns out that it’s possible, and that these ideas are wildly popular. So this is a message for not just establishment Democrats, but for everyone. Because it also means that we have to figure out why we’re not making it all the way. Let’s remember that Labour came close, but they didn’t win.

— Naomi Klein

Corbyn’s rise, though, is such a repudiation of the takeover of politics by the logic of corporate branding. That whole process was really kick-started by Tony Blair. When I was writing No Logo, although eons ago, it was shocking that Tony Blair talked about Labour as a brand. They were using this language of rebranding, calling it the “New Labour Party.” The idea of treating a political party as a brand was new. And he went on to treat Britain as a brand. He relaunched Britain under this slogan, “Cool Britannia,” which you’re too young to remember.

ITT: That’s horrible.

NK: Yeah, what I wrote in No Logo was that Tony Blair’s party was a “Labour-scented party.” It explicitly deracinated the word labor from its meaning, in the same way that these companies were deracinating their brands from the products that they were selling. What I found so moving about Corbyn’s campaign was that when the Labour logo appeared at the end of his ads, it meant workers. It meant being aligned with workers and having the trust of working people. It ceased being a brand and became a description of the values and policies of the party. That’s an important shift, especially because a lot of Democrats think that the way to beat Trump is to come up with a better-branded billionaire.

ITT: Some of the language you use to describe branding sounds a lot like the language used by political theorists to describe populism’s effect on people — giving people a sense of belonging to a larger group, being able to transcend their material conditions. These things are, of course, absurd to read onto something like a pair of sneakers. But are there aspects of branding that can be salvaged by movements, especially when “the resistance” seems to be struggling to come up with a coherent identity?

NK: The kind of branding that I was writing about in No Logo was what I was calling “hollow branding,” where the idea that you’re selling basically has no relationship to the reality of what you are offering. And that is a concept that I don’t think should be redeemed. So maybe it’s helpful to make a distinction between that and using the best communication and design skills that are available to get a vision and a platform and a message out. I’m all for that. But I’m not sure I’d call it branding. I really think that phrase may be poisoned.

There is something inherently possessive about branding, because brands compete with other brands for market share. And I think that the way in which political groups — not just political parties but campaign organizations, NGOs, even individual people — have come to think of themselves as brands and apply to politics this very proprietary logic of the corporate world has done tremendous damage to movement building. Brands compete with one another for market share, while movements want to work with whoever wants to reach the same goal.

So I’m all for using great design where it’s useful to have a common umbrella so that people feel part of something bigger than themselves. But I think we need to be very aware of when thinking like a brand becomes a problem — when we’re making decisions based on protecting our brand as opposed to on building the largest movement that we can, which is much more of an open-source ethos.

ITT: You talk about Trump as the accumulation — the Frankenstein monster — of trends that you’ve written about for years, from hollow branding to the shock doctrine. Do you anticipate anything unique about the way Trump is likely to respond to an external shock, whether it’s a terrorist attack or a natural disaster?

NK: I don’t think it will be unique; I think it’s kind of an evolution. But I do think Trump’s admiration for authoritarian figures — authoritarian leaders and authoritarian tactics — is a shift. Bush and Cheney didn’t ban protests after 9/11. They could have tried, and they did a lot of other things to try to silence dissent by trying to associate any serious criticism of the United States with terrorism. But it’s worth noting that they didn’t do what the French government did under François Hollande after the Paris attacks, which was institute a state of emergency banning political gatherings and outdoor gatherings of more than five people.

— Naomi Klein

Given Trump’s clear comfort level with authoritarian regimes, we should expect that his administration would try to do something like that in the aftermath of a terrorist attack. We are hearing open talk about internment on Fox News. The kind of policies that Trump ran on are precisely what we should be very afraid of.

Take him at his word. He said he wanted to ban the entry of Muslims into the United States. He immediately started talking about the need for his Muslim ban after the London terrorist attack. It would be very foolish to reassure oneself that the White House wouldn’t do that. Maybe it wouldn’t, but it’s better to be prepared.

They certainly have learned a lesson from the protests that responded to the introduction of the travel ban. They did not repress those protests in any kind of strong way, but they know that the protests got in their way and emboldened the lawmakers and the courts. I would be worried about his willingness to crack down on protests like that. It’s so important in that moment for there to be just huge numbers of people in the street. If it’s left to the most targeted and most vulnerable communities to defend their own rights, the repression will be much more severe than if this administration finds itself confronted with hundreds of thousands of people of all ethnicities and religious backgrounds in the streets. That is a lot harder to repress, right? At least without serious consequences.

ITT: One of the things that alarms me about Trump is that his staunch climate denialism sets an incredibly low bar — basically anything north of outright denial looks like progress. What has been the impact of this?

NK: I’m not sure so far that he is constraining the climate conversation, if we look at the way states and some cities are reacting to the withdrawal from the Paris Accord. The sort of policies we are seeing put on the table from the mayors of Pittsburgh and Portland — to get to 100 percent renewables by 2035 — are more in line with what science demands and what technology allows than what we were talking about under Obama. Maybe that would have happened anyway, but maybe not.

Obviously the Republicans are doing less than nothing. The Democrats don’t have a clue about what to do, and so into that vacuum have come some real solutions from the local level. I think we see a similar dynamic with that disastrous health care plan proposed by Congress. That’s creating more of a space for single-payer at the state level, right? Pushing for some of the actual policies we need at the subnational level in the US and at the national level outside of the US is what we need to do when we finally get rid of these maniacs and get things caught up to where we need to be.

ITT: Do you see any kind of single-payer-type demand when it comes to climate? Is there anything that captures that type of energy?

NK: Climate is more complex because it’s about changing the backbone of our whole economy. I’m always suspicious when people frame the solution as just one thing, like the carbon tax. We are past that point, and the idea that there could be just one thing, and that that would ever be enough to change the building blocks of an industrial economy, just seems crazy.

A big piece with climate is that getting to 100 percent renewables within two decades requires a huge jobs plan. Of course, it requires different flanks to get there. A jobs plan has to be designed and thought through. That’s why I’ve thrown my eggs in the basket of coming up with a policy platform that connects the dots between the need for unionized jobs, energy democracy and putting frontline communities first in line to own their own power. Part of the problem we’ve had is that some of the jobs we have lost are high-paying union jobs, and the renewable-energy jobs that will just sort of emerge thanks to the free hand of the market will be much lower-waged and non-union. Not fully confronting that and hoping that nobody notices has not been a great strategy in the fight for a so-called green jobs agenda.

ITT: You talk in the book about the importance of intersectionality. One of the points you’ve made is that while the things the Left cares about have been cordoned off into issues silos, the Right sees its efforts as part of this coherent ideological project. Could you explain that a bit?

NK: The right has a holistic vision to realize dominance on every level — over people and over the planet. It is winner-take-all hyper-individualism. These are the connective ideas of the hyper-capitalist project, right? Progressives and people on the Left have not been clear enough about what the connective tissue is of what we want and just how well our ideas are connected. We have a lot of work to do.