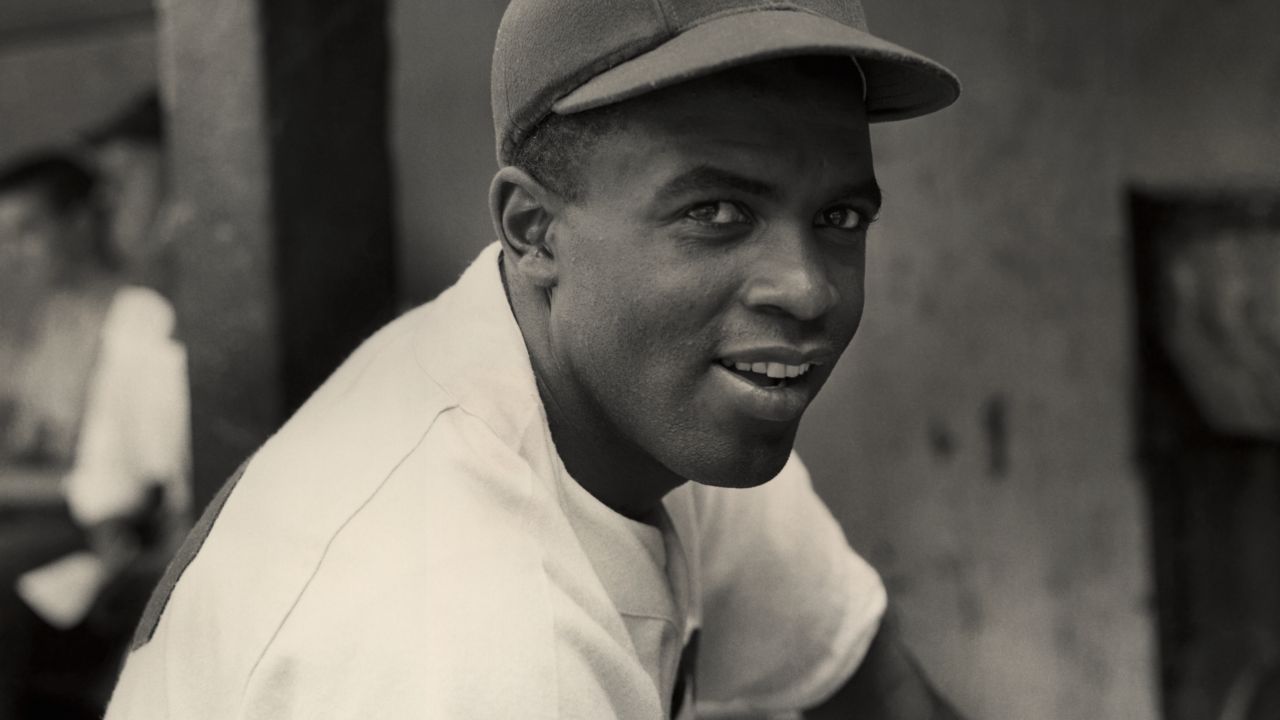

A portrait of the Brooklyn Dodgers' infielder Jackie Robinson in uniform (circa 1945). (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

This Saturday, while every Major League Baseball team will be celebrating the 70th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s achievement of breaking baseball’s color line, hundreds of thousands of Americans will be protesting in the streets as part of Tax Day.

Were he alive today, Robinson would understand the connection. He recognized that his trailblazing accomplishment was not only the triumph of one man but also the result of a protest movement. During and after his playing days, Robinson was an activist and a vocal critic of corporate America’s mistreatment of African-Americans and of racism in general.

On April 15, 1947, Robinson made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, ending baseball’s segregation. In 1997, the 50th anniversary of his rookie season, Major League Baseball retired Robinson’s number — 42 — for all teams. Now, every player on every team wears that number once a year — on April 15. This Saturday, the Los Angeles Dodgers will also unveil a statue of Robinson prior to their game against the Arizona Diamondbacks.

Participants in Saturday’s Tax Day march in Washington, DC, and parallel marches in over 100 cities, will be protesting President Donald Trump’s decision not to release his tax returns and to demand changes to the country’s economic system, which organizers say favors the rich at the expense of the poor.

In today’s America — with a president who was elected and is governing by appealing to racism — it is important to learn the real lessons of Robinson’s achievement. And at a time when racial tensions are flaring in America’s communities, politics and workplaces, Robinson’s story serves as a reminder of the nation’s best impulses — and its worst.

It is difficult today to summon the excitement that greeted Robinson’s accomplishment. The dignity with which Robinson handled his encounters with racism — including verbal and physical abuse on the field and in hotels, restaurants, trains and elsewhere — drew public attention to the issue, stirred the consciences of many white Americans and gave black Americans a tremendous boost of pride and self-confidence. As Americans readjusted to life after returning from World War II, Robinson’s success on the baseball diamond was a symbol of the promise of a racially integrated society. He did more than change the way baseball is played and who plays it. His actions on and off the diamond helped pave the way for America to confront its racial hypocrisy.

Most books, articles, and films (including the 2013 Hollywood movie 42) portray the dismantling of baseball’s apartheid system as the tale of one man, Robinson, who triumphed over adversity — a lone trailblazer who broke baseball’s color line on his athletic merits — with a helping hand from Dodgers president Branch Rickey, the shrewd strategist who recruited Robinson and orchestrated his transition from the Negro Leagues to the all-white Major Leagues, battling the sport’s, and society’s, bigotry.

We may prefer our heroes to be rugged individualists, but the reality doesn’t conform to the popular myth. The truth is that Robinson’s achievement was a political victory brought about by a social protest movement.

That story has been told in two outstanding books, Jules Tygiel’s Baseball’s Great Experiment (1983) and Chris Lamb’s Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (2012). As they recount, Rickey’s plan came after more than a decade of effort by black and left-wing journalists and activists to desegregate the national pastime.

Beginning in the 1930s, the Negro press, civil rights groups, the Communist Party, progressive white activists and radical politicians waged a sustained campaign to integrate baseball. It was part of a broader movement to eliminate discrimination in housing, jobs and other sectors of society. It included protests against segregation within the military, mobilizing for a federal anti-lynching law, marches to open up defense jobs to blacks during World War II and boycotts against stores that refused to hire African-Americans under the banner “don’t shop where you can’t work.” The movement accelerated after the war, when returning black veterans expected that America would open up opportunities for African-Americans.

Reporters for African-American papers (especially Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier, Fay Young of the Chicago Defender, Joe Bostic of the People’s Voice in New York, and Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American), and Lester Rodney, sports editor of the Communist paper, the Daily Worker, took the lead in pushing baseball’s establishment to hire black players. They published open letters to owners, polled white managers and players (some of whom were threatened by the prospect of losing their jobs to blacks, but most of whom said that they had no objections to playing with African-Americans), brought black players to unscheduled tryouts at spring training centers, and kept the issue before the public. Several white journalists for mainstream papers joined the chorus for baseball integration. (In the film 42, Smith is depicted as Robinson’s traveling companion and the ghostwriter for Robinson’s newspaper column during his rookie season, ignoring Smith’s key role as an agitator and leader of the long crusade to integrate baseball before Robinson became a household name).

Progressive unions and civil rights groups picketed outside Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field in New York City, and Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field in Chicago. They gathered more than a million signatures on petitions, demanding that baseball tear down the color barrier erected by team owners and Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis. In July 1940, the Trade Union Athletic Association held an “End Jim Crow in Baseball” demonstration at the New York World’s Fair. The next year, liberal unions sent a delegation to meet with Landis to demand that major league baseball recruit black players. In December 1943, Paul Robeson, the prominent black actor, singer and activist, addressed baseball’s owners at their annual winter meeting in New York, urging them to integrate their teams. Under orders from Landis, they ignored Robeson and didn’t ask him a single question.

In 1945, Isadore Muchnick, a progressive member of the Boston City Council, threatened to deny the Red Sox a permit to play on Sundays unless the team considered hiring black players. Working with several black sportswriters, Muchnick persuaded the reluctant Red Sox general manager, Eddie Collins, to give three Negro League players — Robinson, Sam Jethroe and Marvin Williams — a tryout at Fenway Park in April of that year. The Sox had no intention of signing any of the players; nor did the Pittsburgh Pirates and Chicago White Sox, who orchestrated similar bogus auditions. But the public pressure and media publicity helped raise awareness and furthered the cause.

Other politicians were allies in the crusade. Running for re-election to the New York City Council in 1945, Ben Davis — an African-American former college football star, and a Communist — distributed a leaflet with the photos of two blacks, a dead soldier and a baseball player. “Good enough to die for his country,” it said, “but not good enough for organized baseball.” That year, the New York State Legislature passed the Quinn-Ives Act, which banned discrimination in hiring, and soon formed a committee to investigate discriminatory hiring practices, including one that focused on baseball. In short order, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia established a committee on baseball to push the Yankees, Giants and Dodgers to sign black players. Left-wing congressman Vito Marcantonio, who represented Harlem, called for an investigation of baseball’s racist practices.

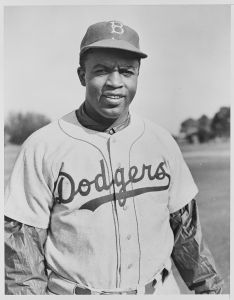

Jackie Robinson in his Brooklyn Dodgers uniform (Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

This protest movement set the stage for Robinson’s entrance into the major leagues in 1947. At the time, America was a deeply segregated nation. The previous year, at least six African-Americans were lynched in the South. Restrictive covenants were still legal, barring blacks (and Jews) from buying homes in many neighborhoods — not just in the South. Only a handful of blacks were enrolled in the nation’s predominantly white colleges and universities. There were only two blacks in Congress. No big city had a black mayor.

The grandson of a slave and the son of a sharecropper, Robinson was 14 months old in 1920 when his mother moved her five children from Cairo, Georgia, to Pasadena, a wealthy, conservative Los Angeles suburb. During Robinson’s youth, black residents, who represented a small proportion of the city’s population, were treated like second-class citizens. Blacks were allowed to swim in the municipal pool only on Tuesdays (the day the water was changed) and could use the YMCA only one day a week.

Robinson learned at an early age that athletic success did not guarantee social or political acceptance. When his older brother Mack returned from the 1936 Olympics in Berlin with a silver medal in track, he got no hero’s welcome. The only job the college-educated Mack would find was as a street sweeper and ditch digger.

Rickey had long wanted to hire black players, both for moral reasons and because he believed it would increase ticket sales among the growing number of African-Americans moving to the big cities. He knew that if the experiment failed, the cause of baseball integration would be set back for many years. Rickey’s scouts identified Robinson — who was playing for the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs after leaving the army — as a potential barrier-breaker.

Robinson’s background and personal characteristics played a role in Rickey’s decision to select him out of the Negro Leagues to break the sport’s color barrier. He could have chosen Negro League stars, like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, with greater experience or more name recognition, but he wanted someone who could be, in today’s terms, a role model. Although Pasadena was deeply segregated, Robinson had lived among and formed friendships with whites growing up there and while attending Pasadena Junior College and UCLA. He was UCLA’s first four-sport athlete (football, basketball, track and baseball), twice led the Pacific Coast League in scoring in basketball, won the NCAA broad jump championship and was a football All-American. He was well-educated, articulate and considered one of the greatest all-around athletes in the nation’s history.

Rickey knew that Robinson had a hot temper and strong political views. In 1944, while assigned to a training camp at Fort Hood in segregated Texas, Robinson, a second lieutenant, refused to move to the back of an army bus when the white driver ordered him to do so, even though buses had been officially desegregated on military bases. He was court martialed for his insubordination, tried, acquitted, transferred to another military base and honorably discharged four months later.

But Rickey calculated that Robinson could handle the emotional pressure while helping the Dodgers on the field. Robinson promised Rickey that he would not respond for at least a year to the inevitable verbal barbs and even physical abuse.

In October 1945, Rickey announced that Robinson had signed a contract with the Dodgers. He sent Robinson to the Dodgers’ minor-league team in Montreal for the 1946 season, then brought him up to the Brooklyn team on opening day, April 15, 1947.

Rickey could not count on the other team owners or most major league players (many of whom came from Southern or small-town backgrounds) to support his plan. But the Robinson experiment succeeded — on the field and at the box office. Within a few years, the Dodgers had hired other black players — pitchers Don Newcombe and Joe Black, catcher Roy Campanella, infielder Jim Gilliam and Cuban outfielder Sandy Amoros — who helped turn the 1950s Dodgers into one of the greatest teams in baseball history.

Robinson, who spent his entire major league career (1947 to 1956) with the Dodgers, was voted Rookie of the Year in 1947 and Most Valuable Player in 1949, when he won the National League batting title with a .342 batting average. An outstanding base runner and base stealer, with a .311 lifetime batting average, he led the Dodgers to six pennants and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962.

Robinson recognized that the dismantling of baseball’s color line was a triumph of both a man and a movement. During and after his playing days, he joined the civil rights crusade, speaking out — in speeches, interviews and his column — against racial injustice. In 1949, testifying before Congress, he said: “I’m not fooled because I’ve had a chance open to very few Negro Americans.”

Robinson viewed his sports celebrity as a platform from which to challenge American racism. Many sportswriters and most other players — including some of his fellow black players, content simply to be playing in the majors — considered Robinson too angry and vocal about racism in baseball and society.

When Robinson retired from baseball in 1956, no team offered him a position as a coach, manager or executive. Instead, he became an executive with the Chock Full o’ Nuts restaurant chain and an advocate for integrating corporate America. He lent his name and prestige to several business ventures, including a construction company and a black-owned bank in Harlem. He got involved in these business activities primarily to help address the shortage of affordable housing and the persistent redlining (lending discrimination against blacks) by white-owned banks. Both the construction company and the bank later fell on hard times and dimmed Robinson’s confidence in black capitalism as a strategy for racial integration.

In 1960, Robinson supported Hubert Humphrey, the liberal senator and civil rights stalwart from Minnesota, in his campaign for president. When John Kennedy won the Democratic nomination, however, Robinson shocked his liberal fans by endorsing Richard Nixon. Robinson believed that Nixon had a better track record than JFK on civil rights issues, but by the end of the campaign — especially after Nixon refused to make an appearance in Harlem — he regretted his choice.

During the 1960s, Robinson was a constant presence at civil rights rallies and picket lines, and chaired the NAACP’s fundraising drive.

Jackie Robinson and his son at the March on Washington, 1963. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Re cords Administration)

Martin Luther King Jr. once told Newcombe, “You’ll never know what you and Jackie and Roy [Campanella] did to make it possible to do my job.”

Angered by the GOP’s opposition to civil rights legislation, he supported Humphrey over Nixon in 1968. But he became increasingly frustrated by the pace of change.

“I cannot possibly believe,” he wrote in his autobiography, I Never Had It Made, published shortly before he died of a heart attack at age 53 in 1972, “that I have it made while so many black brothers and sisters are hungry, inadequately housed, insufficiently clothed, denied their dignity as they live in slums or barely exist on welfare.”

In 1952, five years after Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, only six of major league baseball’s 16 teams had a black player. It was not until 1959 that the last holdout, the Boston Red Sox, brought an African-American onto its roster.

The black players who followed Robinson shattered the stereotype — once widespread among many team owners, sportswriters and white fans — that there weren’t many African-Americans “qualified” to play at the major-league level. Between 1949 and 1960, black players won 8 out of 12 Rookie of the Year awards, and 9 out of 12 Most Valuable Player awards in the National League, which was much more integrated than the American League. Many former Negro League players, including Willie Mays, Henry Aaron, Ernie Banks and Newcombe were perennial All-Stars.

But academic studies conducted from the 1960s through the 1990s uncovered persistent discrimination. For example, teams were likely to favor a weak-hitting white player over a weak-hitting black player to be a benchwarmer or a utility man. And even the best black players had fewer and less lucrative commercial endorsements than their white counterparts.

In the 16 years he lived after his retirement in 1956, Robinson pushed baseball to hire blacks as managers and executives. He even refused an invitation to participate in the 1969 Old Timers game because he did not yet see “genuine interest in breaking the barriers that deny access to managerial and front office positions.” At his final public appearance, throwing the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 of the 1972 World Series, shortly before he died, Robinson accepted a plaque honoring the 25th anniversary of his MLB debut, then observed: “I’m going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day and see a black face managing in baseball.”

No major league team had a black manager until Frank Robinson was hired by the Cleveland Indians in 1975. The majors’ first black general manager — the Atlanta Braves’ Bill Lucas — wasn’t hired until 1977. But as Robinson’s widow Rachel said last year: “There is a lot more that needs to be done and can be done” in terms of hiring and promoting people of color as managers and top executives in Major League Baseball.

Last season, players of color represented 38.5 percent of Major League rosters, according to a report by the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (TIDES) at the University of Central Florida. Black athletes represented only 8.3 percent of Major League players — a dramatic decline from the peak of 27 percent in 1975, and less than half the 19 percent of 1995. Their shrinking proportion is due primarily to the growing number of Latino (28.5 percent) and Asian (1.7 percent) players, including many foreign-born athletes (27.5 percent), now populating Major League rosters.

There are also sociological and economic reasons for the decline of black ball players. The semi-pro, sandlot and industrial teams that once thrived in black communities, serving as feeders to the Negro Leagues and then the Major Leagues, have disappeared. Basketball and football have replaced baseball as the most popular sports in black communities, where funding for public school baseball teams and neighborhood playgrounds with baseball fields has declined. Major League teams more actively recruit young players from Latin America, who are typically cheaper to hire than black Americans, as Adrian Burgos, in Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line (2007) and Rob Ruck, in Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (2012) document.

On opening day this month, 27 of MLB’s 30 managers were white. There are only two black managers (Dave Roberts of the Dodgers and Dusty Baker of the Nationals) and one Latino manager (theWhite Sox’s Rick Renteria). This is a big drop from the 10 managers of color who took the field in 2009.

Two people of color own Major League teams — Arturo Moreno, a Latino, who has owned the Los Angeles Angels since 2003, and basketball great Earvin “Magic” Johnson, who is part of the group that purchased the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2012. As the TIDES report documents, there are few African-Americans, Latinos or Asians among MLB teams’ top management, including only four general managers.

Like baseball, American society — including our workplaces, Congress and other legislative bodies, friendships and even families — is more integrated than it was in Robinson’s day. But there is still an ongoing debate about the magnitude of racial progress, as measured by persistent residential segregation, a significantly higher poverty rate among blacks than whites, and widespread racism within our criminal justice and prison systems.

As Robinson understood, these inequities cannot be solved by individual effort alone. It also requires grass-roots activism and protest to attain changes in government policy and business practices.

Traditionally, pro baseball players have been conservative and cautious, but Trump’s hostile rhetoric toward immigrants, African-Americans and Muslims has inspired a number of them to speak out.

In January, Houston Astros pitcher Collin McHugh criticized Trump after the president attacked civil rights pioneer and congressman John Lewis, claiming that he represented a “crime infested” district in Atlanta that is “in horrible shape and falling apart.” McHugh said, “I live right in the heart of downtown, in District 5. It’s a great place to live. I’ve been there for seven or eight years, I’ve lived in the metro area pretty much my whole life, and I don’t like to see anybody talk bad about it.”

That same month, Oakland A’s pitcher Sean Doolittle condemned Trump’s executive order banning Syrian refugees seeking sanctuary in this country. “These refugees are fleeing civil wars, terrorism, religious persecution, and are thoroughly vetted for 2 yrs,” he tweeted. “A refugee ban is a bad idea…. It feels un-American. And also immoral.” In February, Cardinals outfielder Dexter Fowler, whose wife is from Iran, told ESPN that he opposed Trump’s proposed travel ban from Muslim-majority nations, “Anytime you’re not able to see family, it’s unfortunate,” Fowler said.

On election night, Dodgers pitcher Brandon McCarthy tweeted: “Tonight’s result affects me none because I’m rich, white and male. Yet, it’ll be a long time until I’m able to sleep peacefully.” Two months after Trump’s inauguration, McCarthy was back on Twitter poking fun at Trump’s campaign pledge to “drain the swamp” of corporate and Wall Street influence-peddlers. “Was the ‘swamp’ Goldman Sachs itself?” McCarthy tweeted, referring to the powerful investment bank that has provided top officials in Trump’s administration.

As we confront the reactionary initiatives from the Trump White House and the Republican Congress, Jackie Robinson’s legacy is to remind us of the unfinished agenda of the civil rights revolution and of the important role that protest movements play in moving the country closer to its ideals.