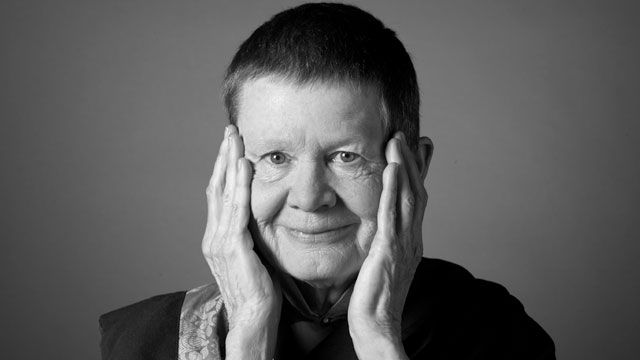

Pema Chadron

At a time when many people feel unsettled and insecure, we present some prose relief. Pema Chödrön’s manual for living, When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Time, has turned 20. Never has its topic seemed more apt. Chödrön, an American Buddhist nun, lays out many methods for living in the modern world with grace. Read an excerpt on working with chaos, reprinted with kind permission of Shambhala Publications. (Below watch a clip of a conversation about faith and reason between Chödrön and Bill Moyers.)

THREE METHODS FOR WORKING WITH CHAOS

The main point of these methods is to dissolve the dualistic struggle, our habitual tendency to struggle against what’s happening to us or in us. These methods instruct us to move toward difficulties rather than backing away. We don’t get this kind of encouragement very often.

We practice to liberate ourselves from a burden — the burden of a narrow perspective caused by craving, aggression, ignorance and fear. We’re burdened by the people with whom we live, by ongoing daily situations, and most of all by our own personalities.

Through practice, we realize that we don’t have to obscure the joy and openness that is present in every moment of our existence. We can awaken to basic goodness, our birthright. When we are able to do this, we no longer feel burdened by depression, worry or resentment. Life feels spacious, like the sky and the sea. There’s room to relax and breathe and swim, to swim so far out that we no longer have the reference point of the shore.

How do we work with a sense of burden? How do we learn to relate with what seems to stand between us and the happiness we deserve? How do we learn to relax and connect with fundamental joy?

Times are difficult globally; awakening is no longer a luxury or an ideal. It’s becoming critical. We don’t need to add more depression, more discouragement, or more anger to what’s already here. It’s becoming essential that we learn how to relate sanely with difficult times. The earth seems to be beseeching us to connect with joy and discover our innermost essence. This is the best way that we can benefit others.

There are three traditional methods for relating directly with difficult circumstances as a path of awakening and joy. The first method we’ll call no more struggle; the second, using poison as medicine; and the third, seeing whatever arises as enlightened wisdom. These are three techniques for working with chaos, difficulties and unwanted events in our daily lives.

The first method, no more struggle, is epitomized by shamatha-vipashyana instruction. When we sit down to meditate, whatever arises in our minds we look at directly, call it “thinking,” and go back to the simplicity and immediacy of the breath. Again and again, we return to pristine awareness free from concepts. Meditation practice is how we stop fighting with ourselves, how we stop struggling with circumstances, emotions or moods. This basic instruction is a tool that we can use to train in our practice and in our lives. Whatever arises, we can look at it with a nonjudgmental attitude.

This instruction applies to working with unpleasantness in its myriad guises. Whatever or whoever arises, train again and again in looking at it and seeing it for what it is without calling it names, without hurling rocks, without averting your eyes. Let all those stories go. The innermost essence of mind is without bias. Things arise and things dissolve forever and ever. That’s just the way it is.

This is the primary method for working with painful situations — global pain, domestic pain, any pain at all. We can stop struggling with what occurs and see its true face without calling it the enemy. It helps to remember that our practice is not about accomplishing anything — not about winning or losing — but about ceasing to struggle and relaxing as it is. That is what we are doing when we sit down to meditate. That attitude spreads into the rest of our lives.

It’s like inviting what scares us to introduce itself and hang around for a while. As Milarepa sang to the monsters he found in his cave, “It is wonderful you demons came today. You must come again tomorrow. From time to time, we should converse.” We start by working with the monsters in our mind. Then we develop the wisdom and compassion to communicate sanely with the threats and fears of our daily life.

The Tibetan yogini Machig Labdrön was one who fearlessly trained with this view. She said that in her tradition they did not exorcise demons. They treated them with compassion. The advice she was given by her teacher and passed on to her students was, “Approach what you find repulsive, help the ones you think you cannot help, and go to places that scare you.” This begins when we sit down to meditate and practice not struggling with our own mind.

The second method of working with chaos is using poison as medicine. We can use difficult situations — poison — as fuel for waking up. In general, this idea is introduced to us with tonglen.

When anything difficult arises — any kind of conflict, any notion of unworthiness, anything that feels distasteful, embarrassing or painful — instead of trying to get rid of it, we breathe it in. The three poisons are passion (this includes craving or addiction), aggression and ignorance (which includes denial or the tendency to shut down and close out). We would usually think of these poisons as something bad, something to be avoided. But that isn’t the attitude here; instead, they become seeds of compassion and openness. When suffering arises, the tonglen instruction is to let the story line go and breathe it in — not just the anger, resentment or loneliness that we might be feeling, but the identical pain of others who in this very moment are also feeling rage, bitterness or isolation.

We breathe it in for everybody. This poison is not just our personal misfortune, our fault, our blemish, our shame — it’s part of the human condition. It’s our kinship with all living things, the material we need in order to understand what it’s like to stand in another person’s shoes. Instead of pushing it away or running from it, we breathe in and connect with it fully. We do this with the wish that all of us could be free of suffering. Then we breathe out, sending out a sense of big space, a sense of ventilation or freshness. We do this with the wish that all of us could relax and experience the innermost essence of our mind.

We are told from childhood that something is wrong with us, with the world and with everything that comes along: it’s not perfect, it has rough edges, it has a bitter taste, it’s too loud, too soft, too sharp, too wishy-washy. We cultivate a sense of trying to make things better because something is bad here, something is a mistake here, something is a problem here. The main point of these methods is to dissolve the dualistic struggle, our habitual tendency to struggle against what’s happening to us or in us. These methods instruct us to move toward difficulties rather than backing away. We don’t get this kind of encouragement very often.

Everything that occurs is not only usable and workable but is actually the path itself. We can use everything that happens to us as the means for waking up. We can use everything that occurs — whether it’s our conflicting emotions and thoughts or our seemingly outer situation — to show us where we are asleep and how we can wake up completely, utterly, without reservations.

So the second method is to use poison as medicine, to use difficult situations to awaken our genuine caring for other people who, just like us, often find themselves in pain. As one lojong slogan says, “When the world is filled with evil, all mishaps, all difficulties, should be transformed into the path of enlightenment.” That’s the notion engendered here.

The third method for working with chaos is to regard whatever arises as the manifestation of awakened energy. We can regard ourselves as already awake; we can regard our world as already sacred. Traditionally the image used for regarding whatever arises as the very energy of wisdom is the charnel ground. In Tibet the charnel grounds were what we call graveyards, but they weren’t quite as pretty as our graveyards. The bodies were not under a nice smooth lawn with little white stones carved with angels and pretty words. In Tibet the ground was frozen, so the bodies were chopped up after people died and taken to the charnel grounds, where the vultures would eat them. I’m sure the charnel grounds didn’t smell very good and were alarming to see. There were eyeballs and hair and bones and other body parts all over the place. In a book about Tibet, I saw a photograph in which people were bringing a body to the charnel ground. There was a circle of vultures that looked to be about the size of 2-year-old children — all just sitting there waiting for this body to arrive.

Perhaps the closest thing to a charnel ground in our world is not a graveyard but a hospital emergency room. That could be the image for our working basis, which is grounded in some honesty about how the human realm functions. It smells, it bleeds, it is full of unpredictability, but at the same time, it is self-radiant wisdom, good food, that which nourishes us, that which is beneficial and pure.

Regarding what arises as awakened energy reverses our fundamental habitual pattern of trying to avoid conflict, trying to make ourselves better than we are, trying to smooth things out and pretty them up, trying to prove that pain is a mistake and would not exist in our lives if only we did all the right things. This view turns that particular pattern completely around, encouraging us to become interested in looking at the charnel ground of our lives as the working basis for attaining enlightenment.

Often in our daily lives we panic. We feel heart palpitations and stomach rumblings because we are arguing with someone or because we had a beautiful plan and it’s not working out. How do we walk into those dramas? How do we deal with those demons, which are basically our hopes and fears? How do we stop struggling against ourselves? Machig Labdrön advises that we go to places that scare us. But how do we do that?

We’re trying to learn not to split ourselves between our “good side” and our “bad side,” between our “pure side” and our “impure side.” The elemental struggle is with our feeling of being wrong, with our guilt and shame at what we are. That’s what we have to befriend. The point is that we can dissolve the sense of dualism between us and them, between this and that, between here and there, by moving toward what we find difficult and wish to push away.

In terms of everyday experience, these methods encourage us not to feel embarrassed about ourselves. There is nothing to be embarrassed about. It’s like ethnic cooking. We could be proud to display our Jewish matzo balls, our Indian curry, our African-American chitlins, our middle American hamburger and fries. There’s a lot of juicy stuff we could be proud of. Chaos is part of our home ground. Instead of looking for something higher or purer, work with it just as it is.

The world we find ourselves in, the person we think we are — these are our working bases. This charnel ground called life is the manifestation of wisdom. This wisdom is the basis of freedom and also the basis of confusion. In every moment of time, we make a choice. Which way do we go? How do we relate to the raw material of our existence?

These are three very practical ways to work with chaos: no struggle, poison as medicine and regarding everything that arises as the manifestation of wisdom. First, we can train in letting the story lines go. Slow down enough to just be present, let go of the multitude of judgments and schemes, and stop struggling. Second, we can use every day of our lives to take a different attitude toward suffering. Instead of pushing it away, we can breathe it in with the wish that everyone could stop hurting, with the wish that people everywhere could experience contentment in their hearts. We could transform pain into joy.

Third, we can acknowledge that suffering exists, that darkness exists. The chaos in here and the chaos out there — this is basic energy, the play of wisdom. Whether we regard our situation as heaven or as hell depends on our perception.

Finally, couldn’t we just relax and lighten up? When we wake up in the morning, we can dedicate our day to learning how to do this. We can cultivate a sense of humor and practice giving ourselves a break. Every time we sit down to meditate, we can think of it as training to lighten up, to have a sense of humor, to relax. As one student said, “Lower your standards and relax as it is.”

From When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön © 1997 by Pema Chödrön. Reprinted by arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, Colorado. www.shambhala.com.

********

In 2006, Bill Moyers talked with Pema Chödrön for the series Bill Moyers on Faith and Reason. Here, Chödrön offers perspective on living in a changing world: “Neurosis is temporary. Sanity is permanent.”

TRANSCRIPT

BILL MOYERS: Do you describe yourself as a person of faith?

PEMA CHÖDRÖN: Well, I thought about this topic, because I knew it was a subject of faith and reason. And faith was not a term that I had ever used for myself. So I gave it some thought, you know. I do have a lot of faith. But the main faith is that sentient beings have the capacity to awaken all beings. And that, given the right causes and conditions, many people who are sort of neutral, and could get caught by the sweep, or a strong seduction towards aggression could equally be swayed toward peace and love and kindness. Because people have that capacity in them. Now this isn’t to say that I don’t see injustice. But I think I’m more of the school of Martin Luther King, you know. Where you want beloved community, where you take the view that wanting everyone to be healed, not wanting to win your side and make the other side wrong. And, OK, underlying this would be that you want for everyone to deescalate their aggression, and not increase their aggression. And I equate that with happiness and peace in the world and so forth.

BILL MOYERS: On almost any day, well I would say on every day in New York you can experience random acts of kindness. But, after 9/11 kindness seemed to be everyone’s daily behavior. I saw so much kindness. And then, of course, it didn’t take too long for it to disappear.

PEMA CHÖDRÖN: OK, so this is like a big view of what happens with individuals. And what we saw in New York, and you see with people who are in those states, that it’s a softness, a kindness, it’s as people said during those days in New York, it’s the only thing that makes sense. And then what happens? The habit comes back. Because, basically, the kindness comes out of not being able to escape from groundlessness. And then, when everyone is in the same situation, you’re all groundless together, the only thing that makes sense is kindness. It’s so interesting, you see, this almost proves, you know, if you’re going to have a proof of faith in basic goodness, that sort of proves it. Then the person who believed in basic badness would say, no, the more fundamental thing is what reasserts itself. And I would say, no, what the Buddha taught was what reasserts itself is the classic texts call it adventitious. It means removable. It’s temporary. Neurosis is temporary. Sanity is permanent.

BILL MOYERS: I like that.

PEMA CHÖDRÖN: But, also, I’ve done dialoguing, interfaith dialoguing when I was, about 10 years ago I did a lot of it. And I came out of it feeling if your view is that of basic badness, you see it wherever you go. If your view is basic goodness, you see it wherever you go. And I said, I might be wrong, maybe basic badness is a fundamental state. But basic goodness makes for a much happier world. And for feeling more at home in the world, and more friendship. So I came out feeling, you know, I’m open enough to, maybe when I die, you know, some big plaque comes up and says, “You were wrong all your life. Everything you believed in your whole life is wrong.” I think I’m preparing for that moment, you know, for it not to be anything that I thought it was. And it would be OK. And do you see what I’m saying?

BILL MOYERS: Have you forgiven your husband?

PEMA CHÖDRÖN: Oh sure. Yeah. Well, not only forgiven him, I tell him, you know, it’s a little insulting to him actually. I say, “You know, your leaving me was the best thing that ever happened to me.” It’s, you know, I’m not sure he’s forgiven me, you know. But sure I’ve forgiven him because, basically, without that, it’s like people who say, “I lived such a superficial life until I found out I had a disease that wasn’t going to get better.” Do you see what I’m saying? Not everyone uses that to get happier. But for a lot of people, when you can’t get rid of it, it sort of brings you to the bottom, and that kind of positive bottom where you surrender, and then things begin to open up for you. Somebody had given me a poem, and it had a line it which was, “Softening what is rigid in your heart.” Work on yourself. Work on your own aggression. And that’s sowing the seeds of peace. It’s not that do this and then the war will be over in Iraq. You know, it’s not naive that way. But it’s talking about sewing seeds of peace. And this is where the meditation comes in. People who meditate, they do become much more in tune with being able to notice that they’ve been hooked and then also notice what they’re saying to themselves at that time to escalate the whole thing. In other words, it does give you more clarity about what’s going on with you.

BILL MOYERS: After over 30 years on this path of enlightenment when you took that vow to be a nun, do you feel you’re close to a state of perfection?

PEMA CHÖDRÖN: No. No. I’m happy. I’m very happy. I feel satisfied with my life. If I died tomorrow, I’d feel I hadn’t wasted my life. But my appetite is insatiable, and I feel I have a long way to go, you know, in terms of perfection.

BILL MOYERS: Who was the Zen master who told his student, “All of you are perfect, and you could use a little improvement.”

PEMA CHÖDRÖN: That’s was Suzuki Roshi. Yeah. “All of you are perfect, and you could use a little improvement.” Yeah. So, you know, one of the things with the bodhisattva warrior, they say that “No matter how far you get in terms of being unhooked yourself, or being happy yourself, or always look back at who you used to be. Never forget to look back at the neurosis that you carried for so many years. Otherwise you’ll lose your contact with the suffering of other people.” So for the bodhisattva warrior, our kinship with each other is the crucial thing, you know. So it isn’t that really you want to avoid the pain of the world, because that educates you about what other people are up against. But the suffering. When I remember earlier I tried to distinguish between pain and suffering? And that suffering is what could lessen, and there could be a sensation of suffering. So you’re not trying to tell people that then there’ll be no bad more things happening to good people. But that the good people will relate to things in a way that doesn’t escalate their suffering, and therefore the suffering of those around them.