Newspaper newsroom, April 26, 1966. (Photo by Jerry Engel/New York Post Archives / (c) NYP Holdings, Inc. via Getty Images)

If our first fake news election turns out to mark the end of democracy as we know it, I think I can pretty precisely date when the end began.

More than 20 years ago, I and a bunch of other Washington journalists were packed into a classroom at American University for a weeklong boot camp designed to teach us about computers and this new-fangled thing that was just beginning to be called the internet. One of the guest speakers, a self-described “technology guru” for the then-fledgling Clinton administration gleefully informed us that we were all dinosaurs. Politicians like his boss, he said, would be able to use the internet to deliver their messages directly to the people, unfiltered by the media.

How ironic, then, that those very tools were so effectively used to prevent a second Clinton administration.

Swords are double-edged. And, as Prometheus taught anyone who happened to be paying attention, technologies, once unleashed, tend to outrun the grip of their would-be masters.

Tweeter-in-chief, are you listening? Because the great mandala might not be finished turning.

As I wrap up my work this year for BillMoyers.com — one of the most satisfying stints in my nearly 40 years as a professional journalist because of the high-caliber people with whom I have been privileged to work — I am convinced that if anything good comes of this year, it will be the renewed interest it has prompted in the nuts and bolts of democracy and the things we do to preserve it. One of those is the free flow of information. Good information. News that informs, not just titillates.

As has been pointed out over and over again in this space by our media critics Neal Gabler, Todd Gitlin and Alicia Shepard, “fake” news isn’t just the made-up kind you see on your Facebook feed (the new supermarket tabloid rack). Fake news is also “breaking news” purveyed by TV stations that then feed you a breathless headline about some VIP (or candidate) doing or saying something meaninglessly incremental. Fake news is talking heads instead of issues. Fake news is bothsideism. Fake news is all of those things real news outlets have begun to resort to in the absence of the resources and the will to cover the real thing.

But people are pushing back.

It is slow, painstaking work, much of it done for little remuneration and well below the national radar — certainly below the radar of Chartbeat, the gizmo that rules far too many newsrooms by advising editors of what’s getting clicks and what’s not. And it’s not just about what we hard-bitten reporters would call “the news.” It’s about making connections: teaching an inner-city kid the gumption to ask a question or driving 80 miles in a snowstorm to meet 11 people at a local library, as Maine husband-and-wife publishing team John Christie and Naomi Schalit did for one of their “Meet the Muckrakers” sessions.

These are just some of the things that people working to reignite journalism at a grass-roots level are trying. Because they are all hard-nosed reporters, they’d be the first to tell you the jury is still out on whether they will succeed. But if they do, it will take the support of the communities they are trying to cultivate. In an era of fake news, it pays to be a more discerning news consumer. In an era when all of us are — thanks to Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat or the social medium of your choice — publishers, it pays to learn what it takes to be a reporter.

What we shouldn’t forget

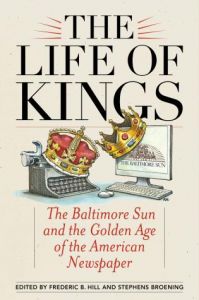

For a vivid example of what real journalism looks like, The Life of Kings, a just-published series of essays by Baltimore Sun reporters, describes what their paper was like before (as has happened at too many other papers) digital advertising gutted newsroom budgets and investment companies bought out more civic-minded owners to fire-sale the wreckage.

Because the book is written by reporters, it’s an honest description of an organization that, like many of its day, could be racist and sexist (though one lively chapter by Muriel Dobbin recounts how she became the first woman in the paper’s Washington bureau). But it also was one of the top newspapers in the nation, in part because it was built upon a meticulous program that was designed to train and nurture young reporters while giving Baltimore readers a depth of local coverage unimaginable today.

“The Sun newsroom typically had beat reporters covering the statehouse, city hall, Baltimore County, Anne Arundel County, Howard County, Harford County, the Eastern Shore, city courts, state courts, federal court, labor, poverty/social services, state politics, housing, transportation, aviation, the police districts, zoning/planning, regulatory agencies,” one of the paper’s former editors, Stephens Broening, writes in his introduction. And these beats were assigned only when a reporter had won the “absolute confidence of the desk” with a series of stories carefully vetted by editors and the rewrite desk. Too bad legendary quote-pipers Jayson Blair or Stephen Glass didn’t have that kind of supervision.

Such legends as longtime New York Times columnist Russell Baker and The Wire’s David Simon were not exempt: Both contributed essays on their grueling apprenticeships on the police beat, the entry point for every Sun newbie. “Young Baltimore Sun reporters harboring the most lurid and secret ambitions for their careers could go a week or more without a byline while working the 4-to-12 shift,” Simon writes.

Unsaid but important to point out is the benefit to the community. All of that “lurid and secret” ambition was directed at people and institutions that now get little, if any, notice. Today there’s so little coverage given to what Chartbeat-driven newsrooms have come to disdainfully call “process stories” that American voters — especially the younger ones — could be forgiven for assuming that there’s just ONE office that counts when they go to the polling booth and also forgiven for being shocked, shocked when that one individual doesn’t magically solve all of the nation’s problems.

In all too many corridors of power today, the hall monitors have disappeared. My own experience of nearly four decades covering politics have convinced me that one of the most important roles of journalism in democracy is not just calling out corruption, but deterring it. It’s just human nature that we tend to stand up straighter and behave better when we know someone’s watching. When we think we’re on our own, it’s easier to fall prey to temptation.

Comeback kids?

Besides the reports of upticks in subscriptions and donations to news organizations in the wake of the election, there are other signs of new journalistic life nationally. Whistleblower and former journalist Wendell Potter is starting Tarbell, an online news source named after famed muckraker Ida Tarbell that will investigate corporations and focus on “solutions-based” journalism. Investigative journalist David Cay Johnston is launching DC Report, focused, he says, on “covering what the federal government DOES, unlike the mainstream news, which tends to cover what officials SAY.” The excellent ProPublica, one of the first nonprofit news sites, is expanding into Chicago. But some of the brightest shoots are sprouting at the grass roots, where new organizations are building not just newsrooms, but communities around them.

In Orange County, California, the Voice of OC, emblazons its mission on either side of its masthead: “Give voice to the voiceless” and “Hold people in power accountable.” Launched by investigative reporter Norberto Santana Jr., the site is heading towards its seventh anniversary of providing what he describes as “insider intell with outsider perspective” in the midst of a First Amendment battle lawsuit and while watchdogging a homeless shelter that Santana credits the news organization’s reporting with getting established. Voice of OC’s homepage features a calendar that alerts readers to upcoming municipal meetings.

“We piss off just about everybody at one point in the week,” Santana writes in an an email, “but that means that by the end of the week they love us because somebody else they hate is getting the same treatment.”

At Chicago’s City Bureau, “our newsroom is essentially a coffee shop,” says Darryl Holliday, editorial director and co-founder. “We are journalists who use an organizing tradition.”

That means the weekly workshops are not just for official affiliates of the program. They are for anyone who chooses to come. One taught how to file Freedom of Information requests. Eve Ewing, a well-known poet and writer who teaches at the nearby University of Chicago, led a narrative workshop.

The nonprofit recruits reporters with different levels of experience to work in teams to cover stories from a community perspective and then their work is published by professional partners. The youngest journalists are high school students, meaning they are getting hands-on experience in reporting while learning how government works.

What has come to be called the “teaching hospital method” of journalism — where carefully supervised reporters-in-training do actual work — is also key to some other new ventures. For the last nine years, Al Cross has headed up the Rural Journalism Institute at the University of Kentucky providing news coverage to the tiny (pop. 1,641) town of Midway. Most of the stories appear online, but this year before Election Day, Cross said, his team put out a 20-page print edition, with news of the local races for mayor and state legislature.

— Fred Anklam Jr., Mississippi Today

In one of the nation’s poorest states, two former USA TODAY editors are part of a staff of 13 — most of the rest recent college grads — working at Mississippi Today, an online-only publication. At a time when the state’s largest newspaper, the Clarion-Ledger, has been laying off staff and some smaller papers in the state can’t even afford the Associated Press news service, “we have the bodies to go back to more traditional coverage,” says Fred Anklam Jr., one of the founding editors, who describes mentoring young reporters in the style of the Baltimore Sun. “It feels like real journalism,” he says.

During its first nine months of existence, Anklam says, the site’s accomplishments have included forcing the state legislature to reveal details of a contract with an outside consultant and setting straight a transportation commission member who told a reporter: “These meetings aren’t open to the public.” It has been a learning experience for officials who “haven’t been covered in so long” they forgot what it was like. Anklam adds: “The whole drill has been very good for the state.”

Enlisting local officials in their own coverage is key to an effort the media watchdog organization Free Press has started in New Jersey, a state often described as a “news wasteland” over which the two neighboring mega-media markets — New York City and Philadelphia — have cast a shadow that prevented local radio and TV stations from flourishing. “Local Voices” brings together policymakers with reporters — some of them from high school papers, some from the real thing — to discuss better ways to cover the community, says the Free Press’ Tim Karr.

More ambitiously, Free Press is launching a campaign to try to get a dedicated source of funding for local New Jersey news outlets by persuading the legislature to commit to giving them a portion of the estimated $2.3 billion in profits the state will realize from the sale of TV spectrum. Karr, who has worked with many local New Jersey news outlets, says he thinks it’s the only way to preserve the kind of journalism they offer.

“No tried-and-true revenue model has succeeded in making these organizations sustainable,” he says.

Finding long-term financial stability is the Holy Grail for journalism, one that so far has eluded the grasp of the most dedicated practitioners. “We haven’t invented a new model,” says Schalit, who co-founded the Pine Tree Watchdog in Maine for which she just wrote a long series on the struggles of poor single parents. She and her husband, a retired newspaper publisher, describe the formula for making it work: “80-hour weeks, sleepless nights and no salary.” Schalit thanks donors with jars of her homemade “journalism jam” every holiday season (“This year we made 84 jars and had to rent a commercial kitchen”). The jam recipients and other modest infusions of cash (“thank God for the Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation,” Schalit adds) have enabled the duo to add a third employee this year.

Christie says that Pine Tree Watchdog would be able to get more money if it took a partisan stance. And Schalit notes: “It’s much easier to get subject-related funding. But then you can’t be as nimble as you need to be as newspeople.”

The Rural Journalism Institute’s Al Cross, who is trying to raise money to endow his organization, expresses a similar frustration. “Nobody wants to give money for journalism unless they can compromise your independence,” he says. “Everybody’s got an agenda.”

— Lance Knobel, Berkeleyside

That’s one reason another journalism upstart, Berkeleyside, named after the San Francisco Bay Area community it covers, is taking the unusual approach of making a direct public offering to raise money for the capital investment the seven-year-old publication needs to take its work to the next level. Co-founder Lance Knobel says he’s “pretty confident” Berkeleyside is the first news organization to make such a move. To fund day-to-day operations, the website sells ads, collects donations from 1,200 readers and hosts events, such as an annual “Ideasfest” — something Knobel, a longtime journalist, has also done in his professional life.

Started by Knobel, his wife, Tracey Taylor, and their friend, author Frances Dinkelspiel, Berkeleyside now employs eight people — with benefits. But the founders’ pay remains “incredibly tiny,” Knobel says. The real compensation comes in another denomination. “We get enormous psychic rewards. Everywhere we go in this city, people stop us and say ‘thank you.’ It is amazing.”

The sentiments aren’t all that different at the other end of the sociological spectrum. Tim Marema, editor of the Daily Yonder, a website focused on covering issues and policy for what he calls “flyover country,” says he sees building news organizations with deep roots in the communities they cover as a key to making democracy work. He describes himself as a “naive” graduate of journalism school: “My belief was, you feed democracy with facts and information, and informed voters make better decisions.” But, he says, he’s learned that information has to be delivered in a voice and tone the audience can understand.

“We’re talking past each other, and it’s mostly cultural,” he says. To fill a vacuum that has been “filled by right-wing talk shows and Fox News,” he says, “we need some hard-assed journalists with a rural sensibility.” A pickup truck with a gun rack wouldn’t hurt, he adds.

In a recent Facebook post, veteran journalist Dan Rather said that people looking to “push back against the forces of hate and discrimination” should “start local, where face-to-face involvement can have a multiplying effect.”

That message is also being taken to heart by some in the journalism community. In a column for the Nieman Lab, Molly de Aguiar of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, says that for years philanthropic donors “have averted their eyes from the alarming loss of journalism jobs and coverage of local and state issues.”

While much of the attention remains focused on the outcome of the national election, she urges donors to begin “grasping the consequences to our communities when there are no journalists covering city council meetings or providing substantive statehouse reporting to keep elected officials accountable.” And she cautions that while “funders will be tempted to make grants that, in effect, seek to buy coverage in order to promote their agendas,” that would only further undermine trust in the media.

“There is no quick, easy fix to rebuilding capacity for news and information organizations or cultivating constructive dialogue and solutions for pressing issues; it will require sustained philanthropic investment and patience,” Aguiar writes. “But the opportunity here is immense.”

(Contributing: Nancy Day in Chicago)