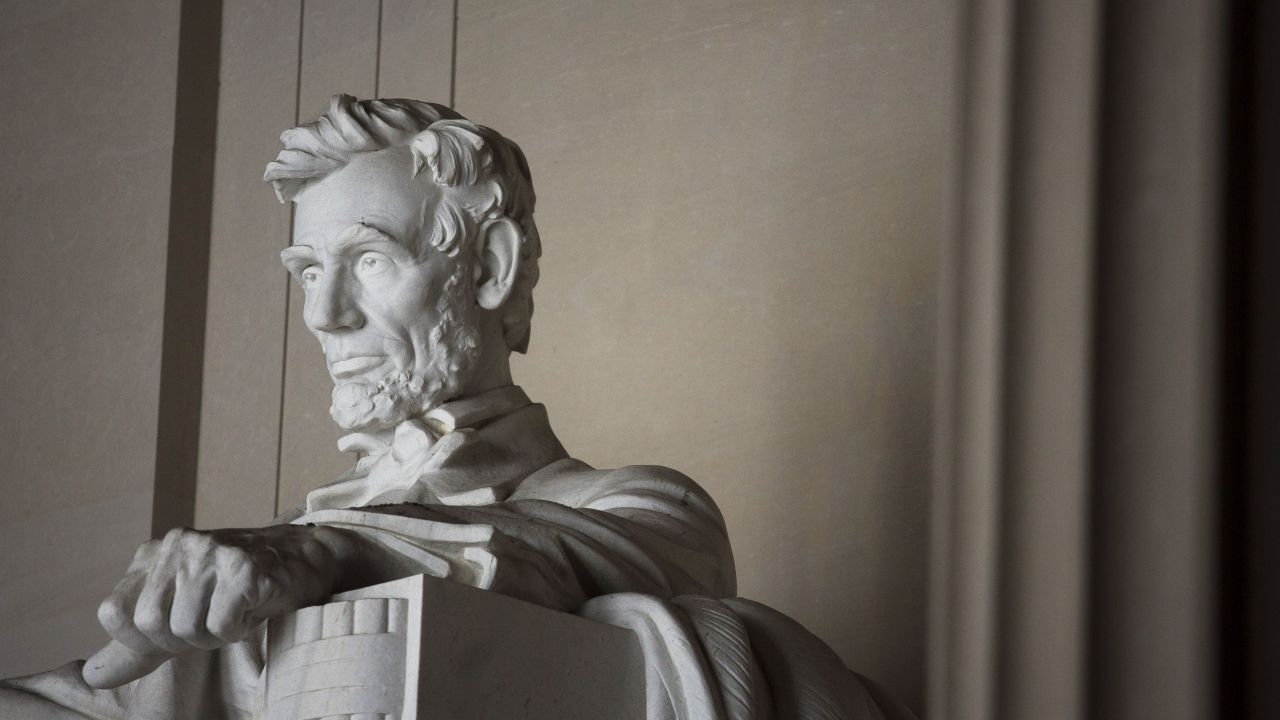

Like Lincoln, FDR and Dr. King, we liberals and progressives have got to remind our fellow citizens who we have been, who we are and of what we are capable, writes historian Harvey J. Kaye. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Americans were ready to make history anew in 2016 — and in a tragic way we have. We elected to the presidency a man who represents not “the better angels of our nature,” but the worst. If we slept at all election night, we woke up on the morning of Nov. 9 chilled and tearful. But as others have written, now is not the time to retreat in sorrow.

We need to take hold of and lay claim to American history.

And we need to advance a progressive American historical narrative.

Apparently haunted by the worst of our national experience, Democrats, liberals and progressives have for too long simply run from the past. But by doing so we merely compound the tragedies and ironies. We turn our backs on the story of the nation’s democratic creed, democratic imperative and democratic struggles and achievements — a story both inspiring and compelling that has been written from the bottom up by Americans in all their diversity.

Fleeing the past, we have allowed conservatives and reactionaries from Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump to concoct a nostalgic narrative. Doing so essentially effaces not only the record of injustices of the past, but also the memory of those persecuted and oppressed and their allies who took hold of America’s promise and succeeded in making the United States freer, more equal and more democratic — at times, radically so.

Echoing Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign slogan, Trump called on Americans to vote for him and “Make America Great Again.” He conjured up an appealing image of a past America that was powerful, stable and ever-growing. But it’s an image that left out the racial, religious and gender discrimination of “those days” (not to mention the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation). And it also ignored the fact that the very things it remembered so fondly were made possible by the democratic empowering of government, the taxing of the rich and regulation of capital, the public works and investments of the New Deal, World War II and the GI Bill — and the making of a labor movement that enlisted 1 of every 3 workers in a union.

Debunking the right’s vision of the past is essential, but insufficient. Not just scholars and intellectuals, but all of the more liberal and progressive politicians and pundits must learn how to speak historically, to refresh and engage America’s memory and imagination. It is not a matter of rallying Americans in favor of restoring a mythical bygone order of things (in our case, the New Deal ’30s or the Great Society ’60s), but of reminding ourselves and our fellow citizens of what can be achieved when by embracing the nation’s radical imperative of freedom, equality and democracy we have risen up, joined together and fought to realize the nation’s finest ideals and aspirations.

Consider the campaigns of workingmen to vote, of both evangelicals and freethinkers to guarantee separation of church and state, of abolitionists and slaves to end human bondage and of labor unionists to organize, gain a voice in industry and secure an American standard of living. Think of how agrarian populists fought to control or regulate banks and railways; of socialists and progressives combating plutocracy, corruption and exploitation; of suffragists working to enfranchise women; of feminist, labor, civil rights and environmental activists enhancing the quality of American life. These heroic struggles made real the Declaration’s promise of equality and the right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” They enlarged the We in “We the People” and the powers of the people that have made America great, indeed, that have made America America.

But during this entire campaign, did we hear of those struggles from the Democrats?

Did we hear them speak strongly and proudly of such figures as Thomas Paine, Frederick Douglass, Walt Whitman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Abraham Lincoln, Ida B. Wells, Eugene V. Debs, A. Philip Randolph, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Martin Luther King Jr. — did we even hear talk of the Founders, the Declaration of Independence, the Preamble to the Constitution — anything about America’s purpose and promise? Did the Democrats tell a story populated by radicals, progressives and fighting liberals? Did they speak of how in the 1770s, the 1860s, the 1930s and 1940s, not to mention the 1960s, Americans confronted near-fatal crises to the nation’s survival not by suspending our finest ideals and aspirations but by actually enhancing freedom, equality and democracy?

Even as Americans were making it clear that they wanted not just change but no less than a political revolution, even as that history was reverberating anew in Wisconsin Rising and Occupy Wall Street, even as young Americans and their elders were joining in the Fight for $15, the anti-fracking and anti-pipeline campaigns, the Moral Monday Movement and Black Lives Matter — and, yes, Trump’s Make American Great Again campaign, too — did the Democrats link those efforts and aspirations to the radical imperative and heritage that we all share?

Our greatest leaders have always spoken historically. Echoing Thomas Paine’s democratic spirit and the preamble to Jefferson’s Declaration, Abraham Lincoln argued that America represented the “last best hope of earth” — the last chance to show that people can govern themselves, making equal rights not just a self-evident truth but a manifest one, and creating a political and economic order in which working people, both white and black, are not compelled to bow to aristocrats and capitalists.

FDR, speaking as if he were History-Teacher-in-Chief, aligned himself with the Democratic Jefferson and the Republican Lincoln, fashioning a narrative that presented America as a persistent “revolution” that not only had to be reaffirmed and safeguarded, but extended and deepened so as to encompass not just “freedom of speech and worship,” but also “freedom from want and fear.”

And delivering even his most political speeches as sermons, Martin Luther King Jr., drew deeply upon both scripture and the historic promise of freedom and equality proclaimed by the Founders, renewed by Lincoln and projected still further by FDR.

At times, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders seemed to recognize the need to lay hold of American history. Clinton launched her 2016 presidential campaign at the new FDR Four Freedoms Park in New York. But she neither stated what those four freedoms were nor referred to them during her campaign. And though Sanders finally spoke of FDR and King when he delivered a speech at Georgetown University explaining what he meant by “democratic socialism,” in the presidential primary debates he repeatedly spoke of Denmark and not the social-democratic tradition in America.

Sanders accomplished miracles in 2016, but he failed to cultivate a narrative for progressive politics. (If he had seen Michael Moore’s film, Where to Invade Next, he might have realized how European social democracy itself stands on American shoulders.)

Progressives are moving forward to transform the Democratic Party: out with the neoliberalism of the Clintons and in with the social-democratic policies and programs of Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Keith Ellison. The Democrats should be the party of freedom, equality and democracy. It’s long overdue, but it’s not enough. Democrats must learn to speak of America’s historic promise, its historic struggles and achievements and its historical possibilities.

If the members of a newly reconstituted Democratic National Committee do not know about America’s radical, progressive and social-democratic traditions — and I bet that many of them do not — they must study up fast. And if they don’t appreciate that progressive change requires more than smart policies and programs, they must be educated to do so. As FDR said in 1935, “New laws, in themselves, do not bring the millennium.” In fact, the DNC ought to issue history syllabi for new members and organize classes for party leaders and prospective Democratic candidates high and low.

Like Lincoln, FDR and Dr. King, we liberals and progressives have got to remind our fellow citizens who we have been, who we are and of what we are capable. We need to articulate and cultivate a narrative that affirms and encourages democracy’s hopes, aspirations and energies. We need a narrative that compels and propels democratic action and political victories.