Ukrainian journalist and member of parliament Serhiy Leshchenko holds papers in front of a screen displaying a picture of Donald Trump's ex-presidential campaign chairman Paul Manafort during a press conference in Kiev. (Photo by Sergei Supinsky/AFP/Getty Images)

Back in 2008, when John McCain was running for president, McCain’s campaign manager, Rick Davis, came under a bit of scrutiny for his lobbying work.

The difficulty was that the McCain campaign had tried to put in place a policy that would bar “registered” lobbyists from working on the campaign. It therefore took some pretzel logic to explain how Davis, who had been a registered lobbyist as recently as 2005 and had been doing influence-related consulting and advising work since, did not meet the definition of a lobbyist.

But such pretzel logic is common among guys like Davis — political operatives who float in a nether sphere where they essentially make their own rules and dare the regulators and watchdogs to tell them otherwise. And it’s a real problem.

I start with Davis because a side note in the stories about Davis was that his business partner was a guy by the name of Paul Manafort, who would become Trump’s campaign chairman eight years later. At the time, it was revealed that Manafort had been working with a man by the name of Viktor Yanukovych. Yanukovych, who had variously been president, prime minister and out-of-power agitator in Ukraine, is an ally of Vladimir Putin.

Under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), lobbyists who represent foreign officials in the United States are required to disclose those relationships. But Manafort had not disclosed his relationship with Yanukovych.

All this is relevant now because Manafort’s ties to Yanukovych have increasingly become major news over the last few weeks, and apparently enough of a liability to the Trump campaign that Manafort is now out as Trump’s campaign manager.

And while the musical chairs campaign gossip makes for obviously entertaining news, it’s important not to lose sight of the larger picture: the fact that the legal landscape around lobbying allows operatives like Manafort and Davis to flourish financially with only minimal disclosures and oversight.

They are men who play by their own rules, daring the powers that be to call them out on it and actually try to enforce any relevant laws. And that they’ve succeeded swimmingly speaks to a larger challenge in regulating lobbying.

The business relationship Manafort failed to disclose through FARA appears to have been worth a lot of money.

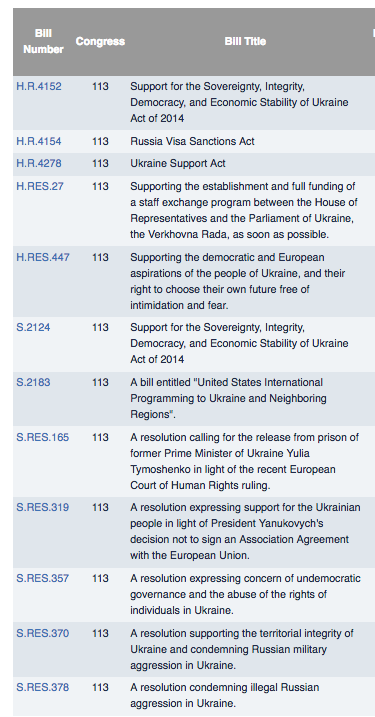

The Associated Press has reported that Manafort and his colleague Rick Gates (also a Trump campaign strategist) appear to have been deeply involved with a Brussels-based nonprofit, the European Centre for a Modern Ukraine (ECFMU), which appears to have been little more than a pass-through front for Yanukovych. The ECFMU spent $2.2 million on lobbying from 2012 to 2014, advocating positions in line with Yankovich’s government. Below is a list of legislation the group’s lobbying firms worked on in 2014, courtesy of OpenSecrets.org

(Source: Center for Responsive Politics)

Perhaps more murkily, New York Times reporters found an estimated $12.7 million in undisclosed cash payments from Yanukovych’s party to Manafort. Again, none of these activities were disclosed. And that’s a lot of money.

It’s still unclear whether Manafort did anything illegal. Certainly, his lawyers deny it. But he’s played fast and loose with the boundaries of the law. And he’s gotten away with his kind of stuff for decades, working for foreign dictators and receiving money in roundabout ways.

By all accounts (like this impressive compilation from Franklin Foer), Manafort has been very good at what he does, helping many a reprehensible tyrant soften his image enough to win US foreign aid. And all the while, he has left only the most scattered of breadcrumb trails in public disclosures, flouting whatever rules are supposed to put guardrails on this kind of activity.

There are rules, and many lobbyists follow them dutifully, filing quarterly reports with the House and the Senate, disclosing their clients.

But then there is a whole larger world of “shadow lobbying” — a world of consultants and advisers and lawyers and “government relations professionals” who are fully engaged in political advocacy, but do not see fit to tell anybody publicly about it.

By one reasonable estimate, produced by political scientist Tim LaPira, these unregistered lobbyists account for about half of the lobbyists in Washington, DC. Put another way, if annual reported lobbying expenditures are about $3.2 billion, a more accurate estimate would be $6.4 billion. Of course, that doesn’t count the countless dollars that flow to nonprofits and research institutes and academic centers designed to add a patina of legitimacy to the narrow demands of corporations and foreign governments.

The same goes for foreign lobbying. There are rules. And then there are ways to avoid them.

Back in 2008, Democratic Sens. Chuck Schumer (NY) and Claire McCaskill (MO) saw a political opportunity in highlighting the gaps in FARA, and pushed to require lobbyists to disclose more information about their foreign lobbying. Their bill never became law. FARA remains poorly enforced because of limited funding, and its database remains difficult to search and full of bad data.

Likewise, despite numerous efforts at expanding lobbying disclosure requirements to cover more activity, the rules haven’t changed. It’s easy for influence peddlers to walk like lobbyists, talk like lobbyists and get paid like lobbyists without ever having to declare themselves as such.

Why should we care? Typically, the case good-government advocates make for disclosure laws is that they help the public to better understand what is happening with their government. They help watchdogs to hold the process accountable. But they also help government decisionmakers to better evaluate the information they receive by understanding where it is coming from, and what kinds of biases might go into its production.

Perhaps one positive aspect of the Trump campaign is the crystal-clear case it has made for lobbying reform: If a foreign leader is going to have a pipeline to an aspirant for the highest office in the land, the public has a right to know. And if the rules that give the public that right are flouted, there should be consequences. This time around, dogged work by investigators and reporters in the Ukraine have made up for Manafort’s lack of disclosure. Next time we might not be so lucky.