Bill Moyers talks with the former governor of California and as yet undeclared candidate for president, Ronald Reagan, at his ranch. Reagan talks about wanting to become president, his parents and upbringing, his early support of New Deal politics and subsequent shift to conservatism.

Although we don’t have a clip from the original video, we do have this short animated film created by Blank on Blank using the audio track.

TRANSCRIPT

BILL MOYERS: What people do you think you represent in 1979?

RONALD REAGAN: Well — I think maybe the same people that elected me to governor in California, which is a state that’s almost two-to-one Democrat; and I won by a million votes. So I must be able to cross the spectrum. When people— that is the thing that meets me; back East. when I go there and find that I have an image of having horns and a tail and so forth, how do they think I got elected out here?

BILL MOYERS: (over freeze frame of Reagan) Ronald Reagan talks about his career, his philosophy, and his ambitions. (BMJ opening.) I’m Bill Moyers.

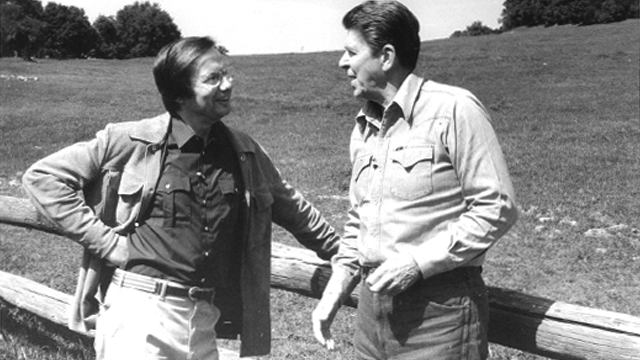

(over shots of Reagan and Moyers walking on Reagan ranch) Ronald Reagan lives in Los Angeles, but comes as often as he can to this ranch in the hills north of Santa Barbara, California.

He and his wife, Nancy, bought this place several years ago and turned the old adobe cabin that was here into a modest but comfortable house. The former actor, twice the Governor of California, comes here to ride, relax, work with his hands — he and a friend put up that fence — and to ponder his future. He has not announced his candidacy yet, but the polls say Ronald Reagan is the clear front-runner for the Republican nomination for President in 1980. The last time he ran, against Gerald Ford in 1976, he almost unseated an incumbent President. He lost in part because at times he seemed ambivalent about the race. Now when you call on him, the ambivalence is gone. (In house with Reagan): Governor, why would a man who could spend his retirement years serenely and peacefully in a beautiful place like this want to plunge back into the maelstrom of presidential politics?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, maybe there are some things I think that I can still do that might be of service. You’re right about one thing, I love this … love this ranch. I don’t know, though, that I could be happy spending all my time here. I look forward to it, I miss it when I’m away from it, but I think I also— I want to participate. I’m very concerned about what I think is going on in this country.

BILL MOYERS: There are a lot of people who get their only kicks out of politics, who are driven …

RONALD REAGAN: Oh, no. No, that wouldn’t be true. I — I never wanted to hold public office in the first place, never set out to seek it, was persuaded to do what I did; but must say that found it the most fulfilling thing I’d ever done in my life, the eight years that I was Governor of California. But again, I think you have to pay your way. I think …

BILL MOYERS: What do you mean?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, for all the good things that have happened, you have to put a little back, you have to help if you can. I’ve always felt that way.

BILL MOYERS: You feel you’ve had a blessed life?

RONALD REAGAN: It’s been— yes, I have. I have a great many things to be grateful for, I’m very fortunate.

BILL MOYERS: Tell me something about your mother and father. Your father was an Irish Democrat, a union man and a shoe salesman.

RONALD REAGAN: Well, not a union man. He was a shoe salesman, he was a Democrat, he was Irish; and it was a divided family. My father was Catholic, my mother was Protestant; and she was a very outgoing person, and while we were poor I don’t think we really were conscious of it because the government didn’t come around and tell you you were poor like they do today.

BILL MOYERS: This was when you were in Illinois.

RONALD REAGAN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: Were you really poor, or is that a memory that grows with time, as it has with some politicians I know who remember the log cabin more — (laughs) — more flamboyantly than it was?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, no; I — we lived in a small town, so poverty isn’t like you might find it, for example, in a large city. But no, we — it was from payday to payday with us, and I can remember one dish that I thought was delicious~ and it was only later that I realized why we had it. Have you ever heard of oatmeal meat?

BILL MOYERS: No.

RONALD REAGAN: Well, you make oatmeal, and you mix ground meat with it. Then you make a gravy just out of that, and then you serve that in a big pancake-like thing. Well, that was because we couldn’t afford to have that pancake made of all meat. (Laughing.)

BILL MOYERS: There is a story that you were reluctant to consider an acting career because you wore glasses and you thought the glasses would prevent your ever being on stage. Is that …

RONALD REAGAN: (Laughs). Bill, that part’s wrong. The glasses are wrong. But in the Midwest in those days, you didn’t exactly —well, I would never have known how to begin. Broadway and Hollywood were both two places a million miles away, as far as I was concerned; I’d never been east of Chicago or west of Clinton, Iowa. And I just — you thought that if you said out loud “I want to be an actor,” somebody’d throw a net over you. So what actually happened was finally I thought I saw a way toward something general in that, and that was the athletics which had occupied so much of my life when I got out of college, and radio was relatively new and so was the art of sports announcing. And I decided I could say out loud I’d like to be a sports announcer. And that’s what I became.

BILL MOYERS: How then did you wind up in Hollywood? Did you take a screen test?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, I was broadcasting the Chicago Cubs and White Sox home games in Chicago. In those days a team didn’t have an announcer broadcasting their games, there’d be as many as seven or eight of you broadcasting the same game. And when the Cubs left town on the road, then the Sox were in town and you simply switched over there, you didn’t follow a team. But I was with the Cubs on their spring training trip to Catalina Island. They trained there then, in those days. And there was a musical group from our radio station that had been hired to do a bit in a — they were a country music group — hired to do a bit in a Gene Autry western. And I visited them on the set, and suddenly that hidden longing came out, and while I was here a friend introduced me to an agent, who took me over to Warner Brothers, and they gave me a screen test.

BILL MOYERS: And that was it.

RONALD REAGAN: That was it.

BILL MOYERS: When you first came to Hollywood, as I am told, you were a fairly liberal fellow, almost a one-world liberal.

RONALD REAGAN: Well, I was a New Deal Democrat, yes; had grown up that way. My first vote was cast for Franklin Delano Roosevelt the first time he ran.

BILL MOYERS: What was your vision of the world then?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, of course it was in the Great Depression. Your whole mind was taken up with that traumatic experience for all of us following the crash. And yet again, you can look back and see that there were some good things out of that. Differing from today, in the Great Depression there was a warmth among people, there was a desire to help each other. Status symbols did not exist. If you could get a job mowing a lawn or anything else, anyone you knew thought you were lucky. I went to school and worked my way through, a small school in Illinois. I’m sure that football helped, and the fact that I could play football, but you didn’t get athletic scholarships. My job was — first job was waiting tables, second job was one of the better jobs I’ve ever had, washing dishes in the girls’ dormitory. But ….

BILL MOYERS: (Laughs.)

RONALD REAGAN: I think this is what occupied you. And at the time …

BILL MOYERS: That doesn’t make you a liberal, though. (Laughing.)

RONALD REAGAN: Well, no … to this ext— no, because here’s a funny thing. I have often thought the party changed much more than I did. Now, granted, at that time I thought all of the efforts by the government to resolve the problems of the Great Depression were the proper thing, you know, the way to go. I look back now and realize they didn’t help at all; they didn’t cure the Depression. In many ways they set it back. It’s tragic, but the cure of the Depression was a very high price — World War II. But when I say I haven’t changed as much, how many people remember that in 1932 Franklin Delano Roosevelt ran on a program, a platform, the Democratic platform, of cutting federal spending by twenty-five percent, governments authorities and autonomy that he said had unjustly been seized by the federal government? Now, there’s only one party today in America that I know that would be happy with that platform, and it’s the party I now belong to. (Laughing.)

BILL MOYERS: But when you came to Hollywood you were a confirmed believer in the New Deal …

RONALD REAGAN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: … you had an outlook that embraced world liberalism as I understand it. Yet fifteen years later you were the evangelical spokesman for conservatives in this country.

RONALD REAGAN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: What had happened to you in that period of time?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, it was a succession of events. Yes, when World War II was over — and I think World War II probably delayed my realization and maybe many others about some of the New Deal panaceas and our finding out that they hadn’t worked. Because then there was only one thing on your mind: World War II. And I was in the service. But I had believed that possibly there were some things that would be better off if the government ran them. Major industries, or maybe utilities and this sort of thing. And then in the service, I began for the first time — I saw some of government’s operations. I wound up as the adjutant of an Air Force post, army Air Force post, in which we were top-sensitive; we were not allowed to have civilian employees.

And just for one example, when the Congress assailed the Defense Department during the war for hoarding manpower while other industries were having to give up essential manpower to the war effort to be in uniform, they accused the Defense Department. So an order went out for a sizeable cut, about thirty percent or thirty-five percent cut, in civilian manpower in army installations. And suddenly two people from Washington walked into my office at this post as adjutant, and told me that they were screening the post for civil service employees. And I said, “But we’re not allowed to have them.” And they smiled and said, “You’ll have them.” And the next thing we knew we got an order that we were to have 250 civil service employees. And every civil service employee sent to us came to us from another military installation. At the end of meeting the reduction that Congress had ordered, they had more civil service employees than before they started the reduction. They simply spread them out and moved them to posts that hadn’t had any. But each post could say they had reduced.

BILL MOYERS: What did that say to you?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, it was an eye-opener. And then when the war was over and I returned to Hollywood and went through the great experience there, and very deeply involved as an officer of the Screen Actors’ Guild, when there was an attempt by the Communist Party in this country, by virtue of jurisdictional strikes, to take over the motion picture industry, that experience and seeing the hierarchy of organized labor’s reluctance — even though it was their own labor unions that were involved — to do anything about it. And then I was sent to England to make a picture right after the Labor Government had gotten in, the socialist government, in England, and I worked for four months in a picture there, making a picture under those conditions. Rationing was still in effect, the lights had not yet been turned on in London, you were not allowed to have anything but streetlights, no marquees or advertising in windows or anything; and I began to learn some other things. Now, I’ve always said that in Hollywood if you don’t sing or dance you wind up being an after-dinner speaker. So there were several of us that the industry would call on whenever they had to be represented at some convention or some meeting. And George Murphy, Bob Montgomery, myself — there were others — and usually I’d speak about the motion picture industry. But to make it of interest to other groups, I began telling of some of the discriminatory practices that we were victim to, probably because of the bad public relations of Hollywood, that, you know, who’s going to go to bat for big fat Hollywood? And I would make those speeches as a warning that if this could happen to us it could happen to other industries, And finally, one day I had to say to Nancy — I came home from a speaking engagement and I said, “You know, I’ve discovered I am out speaking, whenever I get these invitations, against things, and then every election year I’m helping elect the people that are making this happen.” (Laughing) And I changed.

BILL MOYERS: I’ve always been unclear about what happened when you were head of the Screen Actors’ Guild and the House Un-American Activities Committee accused a lot of people you knew of being Communist sympathizers.

RONALD REAGAN: In Hollywood, most people aren’t aware that immediately after the war, in 1947, we had a horrendous experience here in which a little group of unions that had been taken over, infiltrated and taken over and were Communist-controlled, formed a rump group outside the AF of L Film Council — this was before it was AF of L-CIO. And they called a jurisdictional strike, and the goal was to stop the motion picture industry, to halt it until — their eventual goal, since documented, was to then, with everybody out of work, propose one giant union. Everybody from the producers to the men on the back lot, to the maintenance men would be in this one union; and of course we found out who would control that one union. There was violence; there were thousands of mass pickets outside the studios that were furnished by Harry Bridges’ waterfront workers. We would be called at midnight and told which bus, where our bus would be, a different location every day to get in the bus and go to work. And I arrived one morning to find the bus still in flames from the bomb that had been thrown at it. Homes were bombed. They would stop cars outside the studio, of workers trying to get in, drag them out of the car and in plain sight of everyone open the car door with the window rolled down, shove the man’s arm across the window, and then break it over the window, and send him on into the studio to see if he could do his day’s work.

BILL MOYERS: Did you think these were Communists?

RONALD REAGAN: Unfortunately, we discovered they were. Well, not all the people doing it. But they organized it. And I happened to be on the board of directors of two groups that subsequently turned out to be Communist front groups. And it took me a long time, and they were very clever. And a little group of us — and made up of many liberal people, like Jimmy Roosevelt, Dore Schary, Olivia de Havilland on one group — began to be suspicious of the fellow board members and so forth, that the organization had departed from its original purpose, which was to be an independent citizens’ committee of the arts, sciences and professions, to support political causes that we felt deserved support; non-partisan. And we finally — this little group gathered, and we very carefully wrote a resolution that we knew that no one who was a Communist or a Communist sympathizer could adopt, and we introduced it to see what would happen, only votes on our side. Now, the significant thing is, when — and we were only eight or ten out of a board of sixty and of thousands — when we resigned, the organization ceased to exist. We evidently were the front behind which they were operating.

BILL MOYERS: Lives were ruined. Some innocent people did get blacklisted and their careers Did you have any sympathy for those people?

RONALD REAGAN: I had a great deal of sympathy, but I had just as much sympathy for the people whose careers were ruined by the Communists. They had a list, and if you were on their list the phone stopped ringing and you didn’t get called for jobs any more.

BILL MOYERS: In the early ’50s, for a variety of reasons, you did become the champion of many causes which brought you support from the far right; whether you agreed with them or not, the John Birch Society was praising you, Orville Faubus was praising you, Ross Barnett in Mississippi was saying nice things about you. You became a spokesman for the right. Have you changed since that time, since the early ’50s?

RONALD REAGAN: No, I don’t think so. I never did, and in fact in many instances repudiated some of the support that was spoken in my behalf. I was just as critical of a number of organizations on the other side as I was of the Communist front organizations. No … I came up with a confirmed belief in the people of this country and in the original principles upon which it was based, and still feel the same way: that government is attempting to do things today that properly belong either at a lower echelon of government or belong in the hands of the people. I believe that government exists to protect us from each other, not to protect us from ourselves. For example, I’ll support anything that government does in the line of ensuring that your headlights are bright and your brakes are right and you know how to drive and all of that. I won’t support compulsory helmet-wearing for motorcycle riders even though I think they’re crazy for not wearing one. But that’s their own business, that’s for their protection. I will insis.t that everything else be done to make sure they can’t come across the center divider and hit me.

BILL MOYERS: How would you describe conservatism today as you would like to see it embraced?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, Bill, I think the labels are wrong. They’re distorted in the first place. If it were 200 years ago, the conservatives would have been at Valley Forge and the Tories would be what today so often we call liberals. Because the tory was a person who wanted to maintain the great central power of the throne, and the men at Valley Forge were the men who wanted more freedom and less centralized authority running their lives. The line of the Declaration about the King: “He has sent hither swarms of officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.” Well, today there are swarms of officers harassing the people and eating out our substance. And so I think the labels are turned around.

BILL MOYERS: Here’s a fascinating discussion of American politics by Seymour Martin Lipset, whom I think you probably know, and Irving Louis Horowitz. And they say what I think any presidential contender has to deal with: “There is in this country today a widely held consensus that every American has a right to the basic protections of shelter, food and clothing. By shifting the burdens from individuals to government, the state at once became more powerful and individuals felt more tranquil because someone out there was listening to the complaints. No presidential candidate would dare interrupt this process of welfare beyond some modest cosmetics to make the programs operate more effectively and efficiently or to weed out corruption in its more obvious forms. Even a candidate like Ronald Reagan only marginally interfered with the welfare system while Governor of California.” Given that reality, can you really expect to reverse the dominant tendency of our times?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, here’s what I would like to propose, and I challenge that we only marginally affected it. What bound us in from doing more here in California — and we were the welfare capital, so I’ve had eight years’ experience with this — our welfare case load in California was increasing 40,000 people a month. Good times and bad. When there was full employment, it still went up at that rate. Every economy we made in government, the savings from that economy was going down that road, that welfare road. We finally organized a task force of people outside government and inside to review all of the congressional acts in connection with the regulations — all HEW does, besides transmit the money, and that you could raise yourself if they hadn’t pre-empted the source, is have tens of thousands of regulations; they fill the wall of this room, and they’re changing them so fast that there’s no way to keep up with them.

But we affected welfare enough with our reforms that we reversed that 40,000 a month increase to an 8,000 a month decrease in the welfare rolls. But at the same time, the welfare needy in California, the truly needy, hadn’t had a cost of living increase since 1958. We not only saved billions of dollars in the reduction of those rolls of people who were unnecessarily there, but we were then able for the first time to increase the grants forty-three percent to the truly needy. Because they were still needy under the welfare system because we were spread so thin. Now, when I say we reduced the rolls, Bill, there was never a single case of anyone who ever was heard from who rose up and said, “I am destitute, I was on welfare, they took me off welfare.” Those people just disappeared. And the only thing I can say about it is, they must have been paper people. There is no one in the United States today who knows how many people are on welfare. They only know how many checks they’re sending out.

BILL MOYERS: If you were President, how would you change it?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, I made one suggestion a moment ago, and welfare would be the one I’d start with. Transfer this agency back to the states and the local communities for administration, and transfer with it the sources of revenue to pay for it.

BILL MOYERS: But the revenue sources always come from the people anyway. You’re only transferring, it seems to me, the cost and the burden back to people…

RONALD REAGAN: Ah, but you’re getting rid of one great big layer, extra layer of administrative overhead. It costs the federal government more to deliver a dollar to a needy person than it costs a county. And it costs a county more than it costs a private charity. Now, speaking of that, let me go a step farther — and I’m not advancing this — there is one recognized religion in America, a church, organized church, that to this day has their own welfare system. And it is the most efficient and effective …

BILL MOYERS: Which is that?

RONALD REAGAN: The Mormon Church. Here in our own state, they own farms, they own a canning company, the members of the church, its volunteers, do the work. When a member becomes destitute and is needing welfare, they go to the church, not to the government. And the church then, in the interim, before they can get back on their feet and out in another job, the church puts them to work in one of these industries. Up in Sacramento there’s a canning company. I visited that; I saw women from the church, sitting in there peeling the tomatoes — they were canning tomatoes at that particular time. Those tomatoes go into a warehouse, but also go all over the country to other Mormon warehouses.

BILL MOYERS: What are you suggesting? Not that we turn HEW over to the Mormon Church, but … ?

RONALD REAGAN: No, but what I’m saying is, what if every organized religion in America had done the same thing? What if the great churches of America

BILL MOYERS: But they didn’t.

RONALD REAGAN: … Protestant, Catholic, and all, had done this same thing? There’s nothing so successful anywhere in the world as American charity and good works.

BILL MOYERS: Yes, I understand that, Governor, but they didn’t, which is why, in the Depression, of which you talked about earlier, the government acted; they didn’t, which is why, when people need help they turn to the government and not to the churches, not to the volunteer associations.

RONALD REAGAN: What I’m saying is that bureaucracy may be set up with the most worthwhile purpose in the world, but shortly after it gets into business its primary goal is the preservation of the bureaucracy.

BILL MOYERS: I don’t challenge that; I’ve had experience in government, and I can understand what you’re saying. But what I also see is that the dominant tendency of modern times is toward bureaucratic centralization. For what you did with welfare when you were in the state, and even some of your critics say you did prune the rolls — when you left the Governor’s office, taxes were up, spending was up, there were more people working for the Government of California than there had been before …

RONALD REAGAN: Ohh …

BILL MOYERS: That’s what the studies show, that’s what the records show.

RONALD REAGAN: Oh, now wait a minute. All right. But how many? Let me tell you …

BILL MOYERS: But more.

RONALD REAGAN: Okay; all right. But put some other facts with it. When I became Governor, the state for the previous decade had been averaging a 7,000 per year increase in state employees. 7,000 a year. We were one of the fastest-growing states in the Union. Now there are certain government areas where the number of employees is somewhat determined by the population of the state. So we put a freeze on the hiring of replacements for people who left government service. But for eight years there was a great growth in population. At the end of our eight years, we only had about 2,000 more employees than we’d had when we started eight years before. Actually, in the proportion of how many government employees per capita to the citizens of the state, we reduced the size of government in proportion to the population of the state.

BILL MOYERS: It’s the local and state governments that have been growing in the last fifteen years at a faster rate than the federal government.

RONALD REAGAN: Yes. And how much of that is due to when the federal government, the pressure came on, the federal government. began doing the sharing programs administered out here but run from Washington, and ordered an increase? CETA is an example. The CETA program — Comprehensive Employment and Training — this is supposed to train people for jobs. Well, all they do is put them on a public payroll. And then you find cities that, well, they’ll use the CETA funds just to hire policemen and firemen and so forth, not the regular local funds. And so local government grows. And then if the federal government says, “We’re going to cancel that program,” then everyone at the local level is all in a panic. That’s what Proposition 13 was all about. And …

BILL MOYERS: And in fact it amuses a lot of people that the surplus which Proposition 13 depended upon came about because of a good financial situation in which you left the state when you left. The people down in Sacramento, for example, are very proud of saying that taxes rose faster under you than they did under Jerry Brown. But then they have to also admit that that surplus came about because of those taxes.

RONALD REAGAN: Well, but also they don’t say something else. .I did a thing, I was advised that what I was doing was very politically unwise. Long before Prop. 13 I had felt that the tax structure of California was unbalanced in one area: the homeowner was being taxed out of his home. And that was going on even before I became Governor. And from the first day I was in office I tried to get relief for the homeowner. Finally, the way we did it — and the only concept that we could see at the time, because as a state government you can’t dictate to a city their costs and so forth — I said what we have to do is have a broad-based tax that covers everyone to pay for such things as welfare and so forth and not put it on the property owner. The property owner should be taxed to pay for those services that are associated with property — streets, fire protection, garbage collection and so forth — that’s what property tax should be for. But why should he have to pay an added burden over everyone else because he owned property?

BILL MOYERS: Do you think there should be some national sales tax that would substitute for a reduction in income tax if you were to achieve one?

RONALD REAGAN: No, but I think there are some inequities in the income tax. But here’s what I would rather suggest, before we get into that: I’d rather suggest that the federal government, instead of making our money go to Washington in that round trip, in which, then, when it gets there and they deduct their carrying charge and then a transformation takes place and it’s their money, not ours, they then give us generously back a portion, provided we’ll spend it exactly the way they tell us to spend it. And there’s part of the trouble. The way they tell us to spend it creates extravagance that is unnecessary, following their minute rules and regulations. My suggestion is, how difficult would it be not -only to turn the programs back but to turn back the sources of revenue? For example, instead of grants to the states, what if the federal government just said about the income tax, X percent of this tax shall remain in the states where it is collected, or the states to use as they see fit. I don’t care if they match it out to what the grants are now. But instead of taking grants to Washington, just leave them here to begin with, and save all that administrative procedure and that expensive round trip. Now, that’s just one possible idea.

BILL MOYERS: You raised Proposition 13. Here is a study of the effects of Proposition 13 in Commentary magazine by two men I admire, Seymour Lipset again, and Earl Rabb. And it ends with this: “If the public mood today is against enlarging the power, scope and size of government in order to solve social problems, as advocated by George McGovern, Edward Kennedy or the Americans for Democratic Action, it is also against returning to the laissez-faire, small government philosophy proposed by Ronald Reagan, Milton Friedman or the American Conservative Union. Reagan, however, appears to be shifting. In a post-Proposition 13 speech, he challenged his image as a right-wing person by pointing out that as Governor he’d made the California income tax more progressive and had increased welfare grants by forty-three percent for the truly needy. Evidently, Ronald Reagan at least understands what analysis of the tax revolt tells us: that the predominant public mood is not right-wing but the neo-liberal or neo-conservative impulse to combine support of collective social responsibilities with a suspicion of growing government power.” Now, does that represent your view?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, I’m not quite sure I just understand what all they’re saying. I think any government has to be watched constantly. Senator Benjamin Hill in 1878 referred to the federal government as a corporation. He said he didn’t fear the private corporations; but he feared that great, ever-growing corporation, because if it became unmanageable, who would control it? I say about local government, too, that local government, particularly in your larger cities, has expanded and is doing — its bureaucracy grows. But it is far easier for the people to do what they did with a Proposition 13, to control local government, to see the waste and extravagance, than it is to control it at the Washington level. That’s why our whole structure of government was laid out to maintains much as possible of government at the levels of government closest to the people. We’re a federation of sovereign states, and today, all over America — and we’re finding it here, in this spirit of Prop. 13 — you’d be surprised at the areas. In Los Angeles County, a number of the cities in Los Angeles County no longer have their own street maintenance departments. When they need street work, they contract, they hire a contractor and have him do the work for them. Their costs are running forty-five percent less than those cities in the county that maintain their own street maintenance department.

BILL MOYERS: But I have to raise the very practical nature of politics today. Some of us remember that Gerald Ford was losing in Florida in 1976, until he started playing pork barrel politics. He promised Orlando an international convention, he offered another town a new veterans’ hospital, he tapped a popular conservative for a high role in the Treasury Department, he promised Miami a whole new transit system; and then he beat you. How do you resolve that paradox?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, you resolve it, Bill, because and you are in a position to help with this — you resolve it because I claim that the bulk of the people in this country today have been victimized by a political and economic mythology, a fairy tale that is too widely believed. They have not been taught the relationship between things. When President Ford called that gigantic economic conference at the White House and had economists from the private sector and from all over and of every varying hue come there, a lot of them, the better-known names, particularly those who advocate more government, like Galbraith, Kenneth Galbraith, they were quoted widely. But one woman economist who is the vice president of a large financial firm in the East, made a statement one day that not very many people paid any attention to. She said yes, if you take a public poll and ask the people if they’d like to have the government do this for them, why, she said, you’d probably get ninety percent of them to say yes. But because the way it’s presented, as if — no one talks about that it’s going to cost them; it’s never priced out to them. And the average person says, “Yeah, I’m paying my taxes, why shouldn’t they do that for me?”

This is what happened in Florida. But this woman said suppose you go around and you give each man a hundred dollars. And then you say to him, now how would you like to have the government do this for you? And if they do it, why, we’ll take the hundred dollars, it’ll take the hundred dollars back. She said, see how many people vote for it, how many would rather have the hundred dollars. This is what needs to be done. Reveal to people that it costs more if the federal government does it than if the state government does it. It costs more if the state government does it than it does if they do it in their own community. And this whole thing, for example, of a part of that mythology: walk down in the street, even to well-educated people, and say to them, “Hey, don’t you think that the big corporations and business should pay higher taxes so as to relieve you of the burden?” And they’ll think for one split-second and say, “That’s right, why shouldn’t they pay more tax?” But how many have been told that business doesn’t pay taxes? That every dime of taxes that business pays, it is only collecting it for government; it has to wind up in the price of the product. And the same old joker, Joe Taxpayer, is paying it when he buys that loaf of bread.

BILL MOYERS: Some people say there are two conservative movements in the country today: one, the traditional conservative movement, led by you; and the new conservative movement, led, of all things, by Jerry Brown. Do you believe that he’s co-opted your program?

RONALD REAGAN: (Laughing.) No … you have to wait from day to day to find where Jerry Brown is. Jerry Brown wet his finger and stuck it into the wind on election night, primary election night, when Prop. 13 passed, and Jerry Brown discovered -that it was a good thing to be on the side of Prop. 13. But Jerry Brown — that gigantic surplus that he accumulated is obscene, called so by a member of his own party. When we were in government, I said that no government has a right to a surplus. If we collect more money than government needs to run, you give it back. And over the course of the eight years, I gave back to the people of California, in the rebating of surpluses, in tax credits and so forth, $5.7 billion. We never got quite to the point that we could see the surpluses ongoing enough to say, “Now we can afford to permanently cut the tax rate.” Jerry Brown has not had that problem. We have a progressive tax system, we have a sales tax. The sales tax is a percentage. As the prices have gone up with inflation, the sales tax goes up. As people move higher to keep pace with the cost of living, they move up in higher surtax brackets. Jerry Brown’s surplus was obscene. He should have long since cut the tax rate or at least have given that money back at the end of each year if he didn’t feel he was sure enough to cut the tax rate. The truth is, in California today, because of inflation, every time inflation — the cost of living goes up a penny, the State of California gets 1.7 cents in added revenue. And yet, he has been hanging on to that money, and the truth of the matter is, he has increased — it isn’t a result of economies that he has a surplus; ours was the result of economies, of cutting things that had cost more. And that’s why I was burned in effigy on several campuses, they said I’d cut their budget. But he has raised and increased the spending rate and the size of government at a far higher rate than we ever did in our eight years.

BILL MOYERS: But his recent speech to the legislature sounded as if you’d written it. His rhetoric is all about the cost of cutting government, the size of government, and the expense of government. Both of you do distrust the federal government. What do you think you have in common, and where do you part ways?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, what we may have in common is that we’re both thinking about running for the presidency.

BILL MOYERS: (Laughing.)

RONALD REAGAN: But what he does not follow up with is, his rhetoric bears no resemblance to the way the State of California is being run. His appointees are of a philosophy that has vastly deteriorated the business quality in California.

BILL MOYERS: You still think business is the goose that laid the golden egg?

RONALD REAGAN: You have to believe that. What I’m talking about is the free marketplace and the one difference: our revolution was a philosophical revolution. For the first time in man’s history, we unleashed the individual genius of every man to climb as high and as far as his own strength and ability will take him. This is the secret of our success; this is why, when we were less than seventy years old, scholars from Europe were coming to this country to find out what had created this great miracle. And that’s all ~hat had created the great miracle: free enterprise.

BILL MOYERS: Do you think materialism is the source of our strength and greatness as a country?

RONALD REAGAN: Sure. Because it’s the kind of materialism that is based on individuals wanting better things, more comfort, and there being people with ideas who are free to say, “Hey, I’ll bet the people would like this, I’m going to make it.” Just recently, I saw an example of one. There’s a fella that has invented an aluminum stein handle. Now, you know, if you open a can of soft drink, hold it in your hand, it gets warm very fast while you’re drinking it, and we punch the holes in the top and drink it. Well, this fella’s made a very economical stein handle; you can buy a dozen of them and have them like you have your silverware. You’re serving people cold drinks in the can, you just clamp the — snap the handle onto it, and people hold it by the handle and the drink doesn’t warm up. And he’s going to make a million dollars. (Laughing.)

BILL MOYERS: Jerry Brown says we’re going to have to cut consumerism like that, we’re going to have to cut consumption, we cannot go on consuming as much as we do; and that the job of the next President is to say to the country, “You have to lower your expectations.”

RONALD REAGAN: Yes. And so is Jimmy Carter saying that. The no-growth policy. It’s part of his energy plan. But I like what Mrs. Margaret Bush Wilson, head of the NAACP, the National Association of Colored People, said about that. She said a no-growth policy’s fine for a twenty-eight-year old, $50,000 a year White House advisor. It’s not so good for a fella down there trying to get his foot on the bottom rung of the ladder. And that’s what’s wrong with them. Sure, they can have that monastic life that they want to live and say to all of us that the better days are over. No, they’re not. We live in the future in America, always have. And the better days are yet to come.

BILL MOYERS: Do you think those better days mean more consumption of goods, more consumption of things?

RONALD REAGAN: Certainly. And a wider distribution of the ability to consume those things. That’s the dream of America. The problem isn’t being poor, the problem is — the answer is to get over being poor. And people want more and want better, and they …

BILL MOYERS: How do you think people get over being poor? What’s the way?

RONALD REAGAN: By this — well — (laughs) — by this same way, of the ability and the freedom to rise as far as you can.

BILL MOYERS: But what about the people …

RONALD REAGAN: How did I get over being poor? I got a job as a sports announcer and it led to everything else.

BILL MOYERS: There’s going to be a stampede to the radio stations right away, I’m sure. (Laughing.)

RONALD REAGAN: (Laughs.)

BILL MOYERS: But what about the people who can’t compete, what about the people who don’t have the ability, what about the people who are surplus to the economy…?

RONALD REAGAN: I recognize the need for, let’s say, a government charity called welfare, to make sure that no one, through no fault of their own, finds themselves destitute and unable to feed themselves or clothe themselves or raise their families. But, if government welfare were properly run, the number of clients would be decreasing instead of increasing; because the goal of welfare would be to do what we did with those 76,000 people in California: to see what their problem was, why they weren’t able to take care of themselves. Now, if it’s physical, if it’s an incapacity, haven’t we always been the most generous people about caring for those? If it’s the other, then find out what their problem is and find a way to bring them up — up here with the rest of us and out and able to get along in the future.

BILL MOYERS: All right, you admit a government role for that. What about government’s role in offsetting the negative consequences of the free enterprise business community you talked about when it considers only its financial considerations and not the public good …

RONALD REAGAN: Ah.

BILL MOYERS: Air pollution, water pollution …

RONALD REAGAN: Oh, now. No, now you get back to what I said earlier. Government exists to protect us from each other. The regulations that government exists to have and are necessary is, yes, to ensure that someone can’t sell us a can of poison meat as they did back at the turn of the century when more people died in the Spanish-American War of poison food than died of gunshot. No, that is — that’s proper. Those regulations we need. I want a regulation or regulations that ensure one thing that I happen to know is true: that transportation in America, whether it’s train, bus or airplane, is safer than any other country in the world because of the safety requirements that we impose on things of that kind. I think a lesson that we should have learned right now from the Three Rivers thing and the nuclear plant: we’ve done a great deal with safety regulations, and the record is proof of it on nuclear plants as to mechanical things. But now we learn that those employees had been worked forty days without a day off, and most of the problems at the plant were due to fatigue; they were human error. All right. We have regulations that say that a pilot can only fly a commercial airplane so many hours a month in order to ensure that you don’t have a pilot that’s sitting up there over fatigued. Now we’ve discovered a new area. Maybe we need a regulation in a thing like a nuclear power plant that employees in that highly sensitive area must not be worked beyond a certain point of fatigue, there must be a limitation on their work. No, I support those regulations. It’s the unnecessary regulations that we don’t need. It’s the regulations in OSHA, for example — Occupational Safety and Health Agency — that would have somebody sitting in Washington trying to work out what are the safety requirements for a drug clerk in a corner drugstore out here in a little town on the coast of California. They can’t possibly know the problems or what to do with any of those things.

BILL MOYERS: What would you as President do differently from Jimmy Carter and Richard Nixon to put into practice some of the ideals you’re stating?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, one of the things that I would do that Jimmy Carter didn’t do is I’d try to keep my campaign promises. He just reversed them. But Richard Nixon had a problem that I think the people must recognize -or any other Republican President. We’ve had a few Republican Presidents, but only one Republican President in the last forty-six years has, for one brief, two-year period, had a Republican majority in Congress. One party’s philosophy has dominated the rulemaking in this country because it is Congress that passes the legislation. The few Republican Presidents, if you remember, Nixon — or not Nixon — Eisenhower was known for his vetoes. Because all he could do was try to stem the flood of government programs coming at him from a Democratic Congress. And by 165 vetoes, he did to a certain extent. In that one two-year period that he had a Congress of his own persuasion, there was not even a tenth of a cent of inflation, and there was full employment. And there happened to be peace at the same time also.

BILL MOYERS: Is the answer, then, next year, 1980, to elect a Republican Congress?

RONALD REAGAN: Well … yes.

BILL MOYERS: The problem is that politics and life are messier than we would like to admit they are.

RONALD REAGAN: Yes. I’ve used a line in some of my speeches that we used to say that politics was the second oldest profession, and I have come to know that it bears a great similarity to the first. (Laughs.)

BILL MOYERS: Wh— (laughing) — what people do you think you represent in 1979?

RONALD REAGAN: I think maybe the same people that elected me to Governor in California, which is a state that’s almost two-to-one Democrat; and I won by a million votes. So I must be able to cross the spectrum. When people — that’s the thing that gets me; back East, when I go there and find that I have an image of having horns and a tail and so forth, how do they think I got elected out here? The people, Democrats as well as Republicans, must have liked — (laughing) — what I said.

BILL MOYERS: I hope you don’t take this personally, but a lot of people out there think that California’s kooky, that California is weird; that a state with the John Birch Society and the Symbionese Liberation Army and Manson and … cults and EST and all of these, has to be somehow weird — a state that can produce a Ronald Reagan and a Jerry Brown? (Laughs.)

RONALD REAGAN: (Laughing.) I think we could match them; I think other areas match us. No, I have found that California … first of all, if California were a nation, it would be the seventh-ranking economic power in the world. And I have found that California is still true of what Mark Twain said about it over a hundred years ago. He said, “Californians have a way of dreaming up fantastic deeds, and the tired old world laughs. And then they bring them off, with dash and derring-do, and the tired old world smiles and says, “That’s California for you.” And he says possibly the reason is because the easy and the slothful stayed home. But the people who came here were looking for opportunity. As a matter of fact, whether it’s in politics or in charity or anything else, you’d be surprised the difference in California and another area of the world when you gather the people in a room and say, “Look, we gotta raise some money,” and to see the size of the contributions. And I think part of it is because wealth in California is primarily first-time wealth. You’re talking to the people who earned it themselves and who became wealthy themselves.

BILL MOYERS: Can people that wealthy, that successful, understand that the world also is full of pain, the world also is full of losers? In fact …

RONALD REAGAN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: … somebody described Reagan country as “a land of well-kept lawns and chambers of commerce, dull and square, a nice place to raise kids and have a barbecue.” Do you think Reagan country, that part of America, can see and understand the other America, the America of dirty streets, crime and poor people?

RONALD REAGAN: Yeah, because most of them came from there. Yes, and for them to think that of me and my background — I have said that maybe the difference between some of those people and myself is — and people like myself— is that they can have compassion for someone who’s needy; oh, yes; let’s have a government program to help that person. We all have compassion for those people and the needy. I don’t know of anyone that doesn’t. And as I say, the people in this country have proven it. But I also have compassion for those families out there in America today where the husband and wife is both working, not because she wants to have a career, but because if they’re going to pay the mortgage on the house in this inflationary age, she has to; if they’re going to send the kids on to school, they both have to work. Fifty percent of the wives now working. And they get up in the morning and they pay their bills and they contribute to their church and charity and they send the kids to school; and all they ask of freedom is freedom itself. And they’re getting worse off, not better off with both of them working, because of this inflationary spiral brought on by government deficit spending and all. And I think that there ought to be enough compassion for them, too; for these people that are making this system of ours work. They’re the backbone of America, and who the devil is passing programs for them?

BILL MOYERS: That brings me then to a classified ad L found in a conservative newspaper, opinion journal, The American Spectator; it’s a classified ad, says: “Reagan in 1980. It’s our last chance.” Last chance for what?

RONALD REAGAN: Well, maybe to reverse this thing that is taking us — look, the federal government with a $532 billion budget that you’re talking about is still spending more than it is taking in. The dollar continues to go down in value. As the deficit goes on, we’ve increased since 1940 the currency in circulation by more than a thousand percent. We have less than doubled the goods and services available for the people to buy. So ten times as much money is chasing less than twice as many goods and services, which is the reason; that’s inflation, it isn’t high prices. The high prices are only reflecting the decline in the value of the dollar.

BILL MOYERS: So it’s the last chance to…?

RONALD REAGAN: It’s the last chance to get back to some common sense, maybe they mean, and that’s what I believe in in government, is common sense.

BILL MOYERS: If you run, it seems to me you’re going to be confronted with three … accusations. You’re too old, you’re too reluctant — you’re not that hungry enough to pay the price to become President — and third, you’re out of touch.

RONALD REAGAN: Huh. I don’t think I’m out of touch, at all. And I have a very good memory about all the things back in my life and what happened to help. I have a very good memory about in the eight years the people that we helped here in California. For example, when I started. I’m supposed to be the big reactionary; we only had a state scholarship fund for needy students to get a college education, of four million dollars.. When I left it was forty-three and a half million dollars. As for too old, I don’t— you know, that’s a very funny thing; most of the time, my apologies, the only people who bring it up are .the press. Now, I’ve been on college campuses, and I’ve had the kids coming up and taking my hand and telling me they want me to run for President. And I think … the only place where I was not asked about my age was in West Virginia, and there I had a great answer if they’d asked me, ’cause they just reelected a seventy-eight-year-old Senator. But …

BILL MOYERS: Are you hungry enough for it?

RONALD REAGAN: Hungry enough for that job? Not in the sense of saying, “Oh, I want to say I’m President, I want to live in the White House.” But hungry to do the things that I think can be done and at an age where I’m not looking down the road saying, “How will this affect the votes in the next election?” But to be able from the first day to say: “I can do this. I can try to do this for the people. I don’t have to look down there and say, how is it going to affect the votes, and so forth” -you bet I’m hungry to do that.

BILL MOYERS: From his ranch near Santa Barbara, California, this has been a conversation with Ronald Reagan. I’m Bill Moyers.

This transcript was entered on May 7, 2015.

© THIRTEEN

All episodes of Bill Moyers Journal, including this one, are available for licensing. Find out more about how to license this content at WNET.org.