Acclaimed journalist and essayist Richard Rodriguez speaks with Bill Moyers about how he writes about the intersection of his personal life with some of the most vexing cultural and political problems facing America.

WATCH A CLIP

TRANSCRIPT

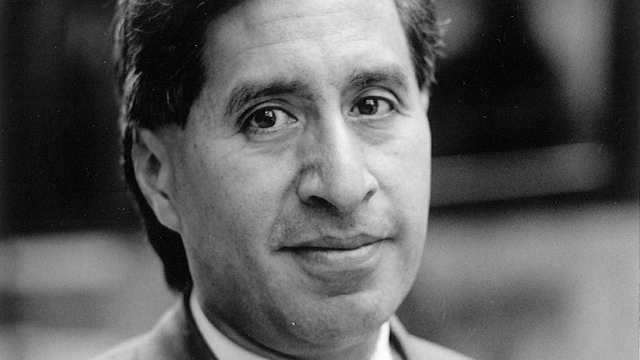

BILL MOYERS: [voice-over] Richard Rodriguez was born in San Francisco in 1944, the son of working-class immigrant parents from Mexico. He spoke only a few words of English when he started school, but went on to become a highly prized “minority” student. With degrees from Stanford and Columbia universities, he studied in London as a Fulbright scholar, but while pursuing his doctorate at Berkeley, he suddenly walked away from a promising career in academia. Despite his ambition to teach, Richard Rodriguez rebelled against job offers which, he says, were coming his way just because of his Hispanic surname. He became a freelance writer, and in 1982 published Hunger of Memory, an autobiography about how education had altered his life. Some critics condemned him for having forsaken his roots and for his negative views of affirmative action and bilingual education, but he was praised by many others for his intimate understanding of the impact of language on life. I talked to Richard Rodriguez recently when he visited New York.

[interviewing] You once said that, of all the people you listen to most intently, you listen to young blacks from the ghetto, because, you said, you admired their brazen intimacy.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Yeah. I guess what I’ve always heard American blacks doing, in some sense, on buses, for example, when they raise their voice against a crowd, is insisting on their separateness in something like the way, as a boy, I used to use Spanish as a way of keeping you away. There’s a great pleasure in intimacy, and a great pleasure in separateness. And it’s a pleasure that people who are dispossessed and people who are kept separate learn to love. The problem is, of course, that when you transfer that language into the public realm, that you already change it, that the black language of intimacy spoken among blacks, overheard by a non-black, becomes a language of separateness. I mean, we hear it very differently.

BILL MOYERS: And that’s why you have opposed bilingual education, for example. You took on the black activists who thought that black English should be used in the schools.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Well, I guess I would say that what I’ve opposed, I’ve opposed the ideological implications of bilingual education, by which I mean, in less fancy terms, whenever people talk to me about using family language in the classroom, that’s when I shudder. I don’t think that classrooms are for family language. I think that, by and large, what happened to me as a boy coming to a bilingual class, for example, is that I would have had to relearn Spanish. Because by and large, the Spanish of my home was family Spanish. The distinctions between family, intimate-circle private language and public language are very severe for me, and I don’t like it when teachers start denying that distinction. I acknowledge that teachers and parents should work together to get the child over that long border between the two worlds, but I think that border has to be maintained. I think those are separate worlds. When I hear educators talk about using family language in the classroom, what I want to say immediately is that there’s no way that’s possible, that there is no way family language exists in the classroom. Impersonations exist, but not family language.

BILL MOYERS: Because it’s not a family, for one thing.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: It’s not a family. Yes, you may get the teacher to trust you more by using Spanish, yes, you may get the student to feel less alienated by hearing Spanish, but the basic lesson of education will be postponed, perhaps denied, perhaps postponed forever, and that is that education is a separation from family, is a movement into another world. When the Irish nun wrote on the board, “Richard Rodriguez,” it was curious to me, because I’d never heard my name pronounced that way, I’d never seen it spelled. Then when she said to me, “Say it after me,” that was curious, too, because no one had ever asked me to say it in a public place. She said, “Speak it to all the boys and girls.” Well, boys and girls already is to introduce me into a world of the classroom, so foreign to me as a so-called minority child, and I simply wasn’t able to do it.

BILL MOYERS: How did you pronounce it?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: That was-that was my problem. The pronunciation wasn’t the problem, it was that I didn’t feel that I needed to speak to you. Do you understand what I mean? I was a minority in the basic sense of that word. I didn’t belong to your world. I didn’t want you. I wanted to live with my grandmother. I wanted to live within Spanish. I wanted to be clothed with it. And here was this enormous Irishwoman with this cross dangling from her breast saying that I had an obligation to speak to the boys and girls. And I couldn’t do it. I simply couldn’t do it. You know, when people talk to me about minorities today, about “Why don’t you want to acknowledge that you’re a minority?” I think to myself of that boy. That boy was a minority. What he needed to do was not linguistic. It was not a linguistic breakthrough. It was a social breakthrough that he needed. He needed to believe that he had a relationship to that public space, that he belonged to public society, in the basic sense of the word minority, that he belonged to the majority.

BILL MOYERS: But the argument for teaching in a bilingual program, as I understand it, is that it is a-it’s a bridge, it’s a facilitating, comforting bridge between the other world of strangeness into the new world, of America. Doesn’t that have some appeal to you?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Not particularly. I thought of education as a more radical process, and not so much unkind, but certainly radical, a kind of radical remaking. I’ve always liked the metaphor of the melting pot, because not only the alchemy suggested by that, but also, it’s violence in some way. I mean, there was a radical remaking of Richard Rodriguez. Now, it came, in my case, with a certain trauma and which I do not recommend to anybody else, but I think a certain clarity of vision about what the classroom was. I did not-I knew what it was about quite early. And I think I’ve never disregarded its value.

BILL MOYERS: It was about remaking you?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: It was about my-the public making of Richard Rodriguez, that’s right. This voice that speaks now -not to boys and girls, but to ladies and gentlemen -this freedom, this enormous freedom to break out of what I call the minority culture. Now, a lot of Hispanics hear that as a betrayal of my ethnic identity. I’m not even talking ethnicity. I’m talking really class here. I’m talking something much more elemental. Ethnicity is, for me, a much more private-in some sense, a much more theological dimension. I don’t think of it as tacos and serapes and kind of weekend trips to a Mexican resort town. I think of ethnicity as having to do with my very soul, and the nature of my relationship to my God. I’ve always thought of my Catholicism as somehow my Mexican side. And my difficulty with Mexico has also been my difficulty with the Catholic church.

BILL MOYERS: But you see, so many people are making the point that it isn’t a melting pot anymore, that, if anything, it’s a mosaic. If it ever were a melting pot, it was a boiling cauldron in which a lot of people got hurt as well as transformed. But it’s a mosaic, many colors, many pieces, one society, and that-

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: But it isn’t. It isn’t that. I mean, my nieces and nephews have German surnames and Scottish surnames. I mean, they don’t-the trouble with glass is that it stays there. It’s-I mean, I remember, I was talking to a Catholic bishop, a Mexican-American in Sacramento, and he said, “That’s what we’re like.” He said, “We’re like that mosaic there.” That’s not what we’re like. I mean, in fact, there are various metaphors Hispanics use to describe the new America. Another is beef stew, believe it or not. I’m not a chunk of beef. I’m not a grocery bag-that’s another metaphor. I’m not a can of beans. America does mix-America’s fluid. It means that I don’t know where I stop and you begin. I cannot predict in meeting you where I’m going to-how I’m going to be changed. I can’t decide it. It’s risky to be an American. It’s risky to live in San Francisco in the 1990s, because I may become Chinese. I don’t know. The idea that I’m going to-that I’m a piece of glass in a mosaic, that that’s an appropriate metaphor, that somehow it’s static, denies the basic fluid experience of our lives. It doesn’t feel that way to me. I mean, the soul is not this ice cube, it’s not this piece of glass; the soul is, rather, water. The soul is more movable. It’s something much more, I would say, even-I think somewhere, I think, that something can be lost. In some sense, I lost my soul in America, if you want to say it that radical way.

BILL MOYERS: Explain that. You lost your soul?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: I lost my Mexican soul in America. I was enchanted by Lucille Ball and by Walt Disney and by Technicolor and by the enchantments of this culture. And by the Protestant singing at the Presbyterian church. And I didn’t want Mexico. In some way, I’m terrified of Mexico. I’ve always thought I will die there, if I go back.

BILL MOYERS: Have you gone back?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Oh, yes, I go back a lot. But recently, very recently, within the last few weeks, a friend of mine, a Mexican who lives in Merida -who is like a lot of Mexicans I know, who is like-very much like my father, is very interested in death, he collects skulls my friend goes to see-he’s very interested in Maya Indians, and he went to see this Indian fortuneteller. He goes to ask her about lotto numbers from the Florida lotto. She refuses to give these numbers out. But he took along a paperback copy of my book, and he asked about me. And she said, “Oh,” when she sees the picture, she said, “Oh, great power there, great power.” He said, “Well, what-you know, what’s going to happen to him?” And she said, “He will die in Mexico.” And which was odd, because there would be no reason for her to see this Mexican-looking face and for her to say that. And so he said, ”Well, how will he die, my friend of the skulls in his house?” She said, “He will be murdered in Mexico.” I guess I’ve always thought about Mexico that Mexico’s lesson is death, and that’s a very wise lesson, that America needs more death in its culture, that I think that we could learn from Mexico in that sense.

BILL MOYERS: What does your father think of you now? Are you still his son?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: That’s a good question. I’ve always been his closest child, that is, I’ve always been the person with whom he’s argued, which is to say the person with whom he’s insisted on a kind of intellectual familiarity. And we’ve taken this argument, over the years, as our kind of love bond, he insisting-he who left Mexico and left who left Mexico during the revolution, during the late parts of the revolution for-Catholic Mexico was undergoing an anti-Catholic persecution where his well-to-do uncle was hiding priests like Tudor England, in cupboards and in closets. My father remembered Mexicans fighting outside the door of the house with knives into the dark, remembering the kind of the mad display of violence in Mexico, remembering the kind of-a priest swinging from a rope in a tree in Mexico, and never wanted to go back to that country. Never. I mean, I said to him, “Do you not miss it? Do you not want to go back?” ”What is there to miss?” So, he’s American.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: He’s American-but in the basic sense-he is Mexican in the sense that he’s a carrier of what Mexico knows, and that is, that it will come to nothing, that it is tragic. And that he looks around America and he is not convinced of it. My father, who put his kids through college and who achieved a two-story house and his big blue DeSoto and his stereo television combination, my father who has seen his daughters go off to junior proms and his sons go off in tuxedos, my father who was surrounded by false teeth grinning at him when he was making them all the years, my father would say, if in fact he would hear you say, as many people have told him, you’ve achieved so much in this country, my father laughs.

BILL MOYERS: At?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: At the illusion that he’s achieved anything at all.

BILL MOYERS: You grew up Catholic, as you said, where religious faith was expressed through-and feelings were expressed through ritual. Latin Mass, I assume.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Yes, Latin.

BILL MOYERS: Do you still go to Mass?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Absolutely. I go every week.

BILL MOYERS: In English?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Well, I go in English because it’s the most convenient language, and it’s the most convenient vernacular language, and I guess I would go to-I would go in Latin, I mean, I would be like even-oh, I would probably go to the Latin Mass in America if there was such a thing.

BILL MOYERS: There isn’t now. You have to go to a ritual of words, not of symbols.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: That’s right.

BILL MOYERS: Isn’t your soul hungry for metaphors?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: It’s very hungry for magic, it’s very hungry for ritual. I think the church is in a very-I mean, I think for all kinds of good reasons the church is in a very bad state right now, liturgically. I think that the church has gotten involved with the world in urgent ways and is asking very important social questions about our society. But I think we’ve lost the basic understanding of religious practice, which is that it begins on your knees. It begins with the assertion of, “I believe.” It begins in the cry of the night to God. And unless you find adequate languages, adequate hymns, adequate ways of doing that, everything else goes very pale after a while.

BILL MOYERS: When you go to church these days, are you forced, as wewere as children, to recognize something about yourself?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: I don’t know. I mean, that’s a good question. 1-thequestion I would like you to ask me, but I’m glad that you haven’t, is the question do I pray, because I don’t know whether I pray. I don’t have the concentration for prayer that I have for, say, writing, when I can intensely concentrate on the text in front of me, when I write. I can’t pray that way anymore, and it’s the thing that frightens me most I don’t know, perhaps I’m not even using my own church to its deepest consolation. I know I’m distracted a great deal and I think about a great-I find it restful. I’m horrified that I come out of church and I know no one-I should say, I know very few friends who go to church. I have very few friends who are Christians. It seems that one of the interesting things about religion is not only that it is communal, by which I mean that it has to be done in-there has to be-it has something to do with community at its deepest, with the we, with the connection to gravestones and to children yet unborn.

BILL MOYERS: Faith is a lonely-

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: It’s lonely, that’s right. That’s the other half of it.

BILL MOYERS: -and going to church does make you realize you’re not you may be lonely, but you’re not isolated.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: That’s right. That’s right. But when you exist as I think most Christians do increasingly in the secular city, it’s-it is quite-it’s a different experience of religion. And it seems to me pre-medieval, in some sense. I come out and here are these, you know, 35 year-old people dressed as children, jogging past in purple shorts and leotards or on bicycles. There’s-in San Francisco on a Sunday morning, between croissants and “60 Minutes” is this kind of celebration of, I don’t know what it is, body, or youth or carelessness.

BILL MOYERS: Now.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: It’s now.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: And I wonder, I wonder about the spirituality of the culture I live in. And I think we are entering a post-Christian age in America, and I think we are beginning to ask questions now that we didn’t ask 50 years ago, even in the kind of the 19th century age of agnosticism.

BILL MOYERS: What questions?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: I think of the way we are asking questions about whether or not there’s a distinction between dolphins and my grandmother, and whether I can make a distinction between them. Whether-whether-the basic questions about the environmental movement and what the Earth is here for. And what my place in the world is. The questions we’re asking about abortion, I think. We’re moving to a post-religious level of rhetoric now which-see, as a Catholic, now, I don’t think there’s a Catholic position on capital punishment, but as a Catholic, I do not think that the worst thing that can happen to a person, a criminal, is to be executed. I think that the worst thing that can happen to any of us is to be damned. That the final judgment is God’s judgment, not man’s judgment. Well, in a secular society, the worst thing that could happen to any of us is capital punishment. I mean, that-I mean, is-is that moment of death. The fact of death is going to ring differently for us. The fact of life is ringing differently for us now. I live in a city, this Chinese city of mine, which is now a city in which death is at the door.

BILL MOYERS: Because of AIDS?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: AIDS. I know a number of people who are dying of AIDS, and in fact, I know about 20 or 30 people right now, which is a lot of people to know. And it’s not so much that I know a lot of people who are dying. I know a lot of young people who are dying. It’s changed my opinion of youth. I don’t look at young bodies anymore the way I used to, as a kind of defense against death. The AIDS epidemic came at the peak of what was, in San Francisco, certainly this utopian outburst. Many Americans would see it as this great, great period of pagan decadence, where men and women who had suffered sexual persecution in Kansas, in Iowa and Illinois had come on the Greyhound bus to San Francisco and there was this immature explosion. You couldn’t get enough sex. You couldn’t go-you couldn’t be out late enough. And people thought they’d found paradise. And suddenly there was death at the door. The lessons of death, the lessons of sorrow that have come to San Francisco, that have come to the gay community in San Francisco, are really astonishing, because when you have sorrow, what you suddenly have is, you have a “we.” You suddenly have people holding together. You suddenly have the necessity for communal existence, which is what, of course, ancient cultures always know.

BILL MOYERS: Is it possible that in this increasing and pervasive awareness of death that you describe in San Francisco and other cities, here in New York, as a result of AIDS, that the soul of Mexico still has something to teach Americans?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Oh, indeed. I think in a way, America-as America ages, for example, and as we end up slower and our eyesight gives way, I think we are going to learn of necessity the lessons of Mexico, that life is not all youth, that life was not all new beginnings. We are going to miss-we are going to miss the consolation of continuity, the fact that we live so far from home, or what we remember as home. We are going to feel alone in the city. I think that-I think in some way, you know, the environmental movement’s insistence on the “we” is this-is this desperate cry of America at the other ends of modernity, telling the pre-modern world, “Don’t come this world.” Literally, “Don’t do what we did to the plains, don’t do what we did to the forests, don’t do what we did to our birds and to our lakes. Save the forests. Save the sky.” You can’t tell that to someone who’s never had. On the other hand, I think that we may have the irony of ironies, America’s destiny, which was once to play the kind of the-the piper to the children of the world. We may become the old men of the world, the old prophets warning people away from modernity.

BILL MOYERS: That is the Indian in you speaking. That is the Mexican Indian.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Oh, yeah. But you see, that isn’t exactly what the biculturalists or what the Hispanics want me to say. I mean, what they want is something-they want-they want me to be better. They want me to be Jesse Jackson. They want me to talk about how we want to get jobs in the city, and how we want to get better housing, and how we want to-you know, we want to be proud of Spanish, and we want to-and we have a contribution to make in this society and we want to be one of the stones in the mosaic and-

BILL MOYERS: You do want those things.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Yes, but that’s not primarily how I see myself. I see myself as a much more subversive, a much dreamier sort of person. I was a very sad child, I was a very melancholic child. I was a child much like a fat girl with bad acne. I mean, I read a great deal, and that’s who I am. I’d lived by myself a long time. I like long summers. I used to read with the little men who had green visors in the Cluny library in Sacramento, and they would read faded newspapers from Detroit and from Philadelphia, and I would read these extraordinary novels. I wanted to know about Texas. I wanted to know about where you were. I wanted to be Texan. One day, I remember, I read William Saroyan, and I found out that I was Armenian. I’d never known that I was Armenian. And then I read James Baldwin and Baldwin, the young Jimmy Baldwin had written this book of essays called Nobody Knows My Name. It was the first time I read Baldwin. I found out that I was black. No one had told me that I was black. And then I read-I didn’t want to read, although the nuns kept pushing it on me, but I did not read Mark Twain because I was in high school, because I thought it was a kids’ book, and I wanted to read adult books when I was a kid, because I was so precocious. And I didn’t-first of all, I didn’t understand-I’d never understood a kids’ book. I didn’t understand the language of a kids’ book, you know. I couldn’t read Winnie the Pooh. I didn’t understand what it was all about. One summer, one American summer this Mexican kid read Huck Finn. And I almost gave up, and I was trailing Huck, and I couldn’t follow the dialect. And then Jim comes in, and I couldn’t follow that. And I was losing my footing on the levee, and suddenly, somewhere in the middle of that book, I caught sight of the river. And that river is America, and it is mine. One of the things I deeply resent about the ethnic movement in America the last few years is that it has denied me the possibility of being Irish, of being Chinese. I want to be more than myself. I’ve always wanted that.

BILL MOYERS: But you’re talking about the imagination, and ethnicity is a matter of fact. It is a matter of birth, boundaries, inheritance, place.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Writers are always rebels against imagination. We are always-I’m always wondering what the woman feels as she’s giving birth to the child. I’m always wondering what that moment is like on the other side of death. I’m always wondering what it is like-my Negroes, when I were in the 1950s, were rich people, rich white people. I always wondered what they were like. I’ve always wanted to know what the insides of great hotels was, so the first time I had any money, I went off to New York and stayed in the Carlyle Hotel. And I was in college, and I was staying at the Carlyle Hotel, and going to hear Bobby Short. And there he was, singing black music, singing black music to this upper-class white audience. And I thought, this has happened. I have trespassed the boundary. I’ve gone to a foreign country.

BILL MOYERS: You always wanted to be where you weren’t, and wanted what you didn’t have. And that’s very American.

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: Very American and, I think, rebellious the way writers are rebellious. We’re not nice people. I am not the role model, never was, never intend to be. I am the last gringo in America.

BILL MOYERS: Well, tell this gringo, who thinks he may be the last gringo in America, how to deal with the coming of the future. I mean, where I grew up, Hispanics are now increasing in number fives times as fast as we are. In California, Mexico’s children are the population of the future. What does an old gringo do?

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: You are Mexico’s children. What I would ask Americans to be is to be brave. I mean, what I fear is that Americans are afraid of themselves and are afraid of each other and that we are really going to retrench in the next few years. And we are going to use ethnicity for exactly not the celebration of the mosaic, which it never was, but rather the old xenophobic assertion that we are separate, that we are each discrete entities in this country. We are not discrete entities. I am your brother. I remember once, I was on a speakers bureau when I was studying in England, at the American embassy. The American embassy had a speakers bureau. And they would get requests from different groups for-they wanted a Yank to come out and so forth. So I would always go out to one of these rotary societies in one of these small towns in England, and we would sit around in the pub beforehand and they would always be waiting for the Yank to arrive. I was there. But they always imagined that somehow the Yank was some astronaut, you know, that he was going to come in, he was crew-cut and he was blond and so forth and so on. I am the Yank. I am the American. And a lot of people are going to it’s going to take some time to get used to that idea, that Americans look like me.

BILL MOYERS: [voice-over] We’ll continue this conversation with Richard Rodriguez on another edition of the World of Ideas. I’m Bill Moyers.

This transcript was entered on May 19, 2015.