In 1954, 1.8 million children participated in the Salk polio vaccine trials. (Photo: March of Dimes)

Since the end of December, 114 people from seven states have been reported to have measles, part of an ongoing outbreak that originated at California’s Disneyland theme park. The outbreak came at the tail of a record-setting 2014, when the Centers for Disease Control and Submission (CDC) recorded 644 cases of measles across 27 states, the highest since the disease was declared eliminated from the United States in 2000.

Measles is incredibly contagious: 90 percent of non-immunized people who come close to an infected person will contract the disease. The CDC recommends MMR (mumps, measles and rubella) vaccination for all children by 12-15 months (barring medical complications). Yet thanks to science-denying, blogging parents and fear-mongering celebrities, vaccination rates dipped in 28 states between 2006 and 2013. Today, there are 17 states where less than 90 percent of children have received the vaccine, and in certain pockets of the country — like the California Bay Area’s wealthy Marin County — immunization rates are even lower.

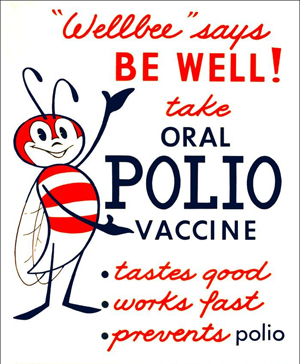

A 1963 CDC poster promoting Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine, a later alternative to Dr. Jonas Salk’s injected vaccine. Together, the vaccines have eradicated polio from most countries. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Many parents who refuse to vaccinate their children incorrectly believe vaccines cause autism and other medical complications, and hold the short-sighted view that diseases like measles and polio are no longer a threat. (Of course, but they’re only a non-threat if everybody else keeps rates low by vaccinating their own children.)

This anti-vaccination trend may continue in coming years. In 2009, adults of various ages reported similar levels of support for mandatory vaccination. But earlier this month, Pew Research Center found that 18-29 year olds — many of whom are presumably approaching parenthood — are now more likely than their older counterparts to think vaccination decisions should belong to the parent.

This “not my child” mindset of some parents couldn’t be further from the national feeling in the mid-20th century. In the late 40s and early 50s, there were, on average, 35,000 cases of polio each year. Although most polio sufferers recover quickly, one to five percent experience short-term aseptic meningitis and a small percentage experience lifelong paralysis — which can eventually cause death.

According to the CDC, in response to the polio epidemic:

The nation came together like never before in an effort to create a vaccine to protect children from polio. Millions of Americans raised funds in their communities for research. Much of the funding came through the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (presently the March of Dimes Foundation), founded in 1938 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, himself paralyzed by polio in the prime of his life.

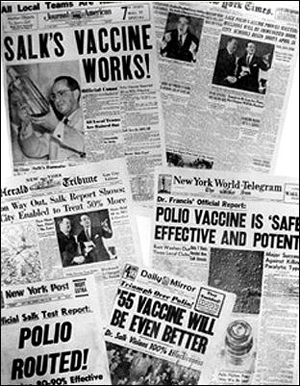

The result was Dr. Jonas Salk’s lifesaving polio vaccine. When it was ready for mass-testing in 1954, 1.8 million children participated and thousands of volunteers assisted. As the CDC described the national attitude, “Everyone had the same goal: victory over polio.”

In 1990, Dr. Salk told Bill Moyers that his interest in vaccines came from a desire “to see what I could do to heal, to counter the negative forces.” Growing up in a world filled with sick children, injured World War I soldiers, anti-Semitism and Depression-era poverty, he explained: “When I had an opportunity to try and create out a place that would bring out the best in people, I took advantage of that. Which is why we’re here… I think that we have an instinct, an impulse, to improve our world. And I think that’s quite universal.”

Mandatory vaccination prevents outbreaks like the one at Disneyland, keeping susceptible people — like babies too young for the vaccine and those with medical complications — safe from exposure. So how is today’s cultural mindset, where 41 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds believe vaccination should be a choice, so far from the national togetherness of Dr. Salk’s era?

There is no shortage of speculation. Forbes suggests that “millennials lack trust in authority figures and institutions,” opting to bypass doctors and the CDC and track down their own information. The Daily Beast attributes the anti-vaccination epidemic to a rise in “pervasive cultural narcissism” — which they say leads some parents to show less empathy, think they should be able to do whatever they want, and believe nothing bad could happen to their family.

The CDC suggests that because young people have no memory of widespread polio or measles, some lack an understanding of their danger. Dr. Anne Schuchat, Director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said in a press briefing last month:

It is frustrating that some people have opted out of vaccination. But we do have a number — really a generation that has not seen these diseases. So whether it’s clinicians who have never taken care of measles before or parents who wonder whether this disease still exists, I think it’s important for us to educate them and remind them that we have safe and effective vaccines.

Parents who decide not to vaccinate aren’t just misinformed — they’re putting others at risk. Those infected with measles experience one-to-two weeks of fever and rash, and the virus can cause ear infections and pneumonia. The CDC estimates that before the development of a measles vaccine in 1963, 400-500 people died each year, 48,000 were hospitalized, and 4,000 suffered swelling of the brain.

As the CDC says of polio, “It’s important to remember that in the 1950s, protecting the public from polio was, in the truest sense, a national project. Every effort was made to see that the vaccine would be widely available to all children and polio would be wiped out.”

Measles outbreaks like the one at Disneyland will continue as long as some parents hold onto their individual focus and misguided need to defy science, disregarding what Dr. Salk saw in the world around him — a universal “impulse to improve our world.”