This post first appeared at The American Prospect and is part of Spring 2015 issue of The American Prospect magazine.

Sign at the 2015 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in National Harbor, Maryland. (Photo: Gage Skidmore/flickr CC 2.0)

According to the news media, 2014 was the year that the GOP “Establishment” finally pulled Republicans back from the right-wing brink. Pragmatism, it seemed, had finally triumphed over extremism in primary and general election contests that The New York Times called “proxy wars for the overall direction of the Republican Party.”

There’s just one problem with this dominant narrative. It’s wrong. The GOP isn’t moving back to the center. The “proxy wars” of 2014 were mainly about tactics and packaging, not moderation. Consider three of the 2014 Senate victors — all touted as evidence of the GOP’s rediscovered maturity, and all backed in contested primaries by the Establishment’s heavy, the US Chamber of Commerce:

- Thom Tillis in North Carolina (a “purple” state at the presidential level) moved to the Senate from being Speaker of the House in North Carolina, where he had been a central player in the state’s sharp right turn. A strong ally of multi-millionaire Art Pope, an arch-conservative and member of the Koch brothers’ inner circle, Tillis sits on the national board of directors of the right-wing American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which in 2011 selected him as its “legislator of the year.”

- Joni Ernst in Iowa (another purple state), touted for her just-plain-folks demeanor and service in Iraq, also has an impressive record of extremist policy positions. During the primary, she called for abolishing the Department of Education, the Internal Revenue Service and the Environmental Protection Agency, and indicated her support for a proposal that would allow Iowa officials to nullify the Affordable Care Act and arrest federal officials who tried to enforce it.

- Tom Cotton, who got the Chamber’s backing in Arkansas, opposed the 2014 farm bill — because it didn’t cut food stamps enough. About the program’s beneficiaries, he said, “They have steak in their basket, and they have a brand-new iPhone, and they have a brand-new SUV.” He voted to voucherize Medicare and raise the Social Security retirement age to 70, and even opposed a resolution of the debt-ceiling crisis, saying that to do otherwise would be “cataclysmic” and default would only create a “short-term market correction.”

Indeed, based on voting records, the current Republican majority in the Senate is far more conservative than the last Republican majority in the 2000s. Meanwhile, the incoming House majority is unquestionably the most conservative in modern history, continuing the virtually uninterrupted 40-year march of the House Republican caucus to the hard right.

The GOP’s great right migration is the biggest story in American politics of the past 40 years. And it’s not just limited to Congress: GOP presidents have gotten steadily more conservative, too; conservative Republicans increasingly dominate state politics; and the current Republican appointees on the Supreme Court are among the most conservative in the Court’s modern history. The growing extremism of Republicans is the main cause of increasing gridlock in Washington, the driving force behind the rise in scorched-earth tactics on Capitol Hill, an increasing contributor to partisan conflict and policy dysfunction at the state level, and the major cause of increasing public disgust with Washington — which, not coincidentally, feeds directly into the Republicans’ anti-government project.

It’s also deeply puzzling. Republicans are gaining more influence even though Americans seem less satisfied with the outcomes of increased Republican influence. Poll after poll shows that major GOP positions are not all that popular. Among swing voters, there has been nothing like the party’s right turn. Political scientists often suggest that the “median voter” runs the show, but on basic economic issues, people at the center of the ideological spectrum express views similar to those of the typical voter a generation ago. On many social issues, such as gay marriage, middle-of-the-road voters have actually moved left. Yet the Republican Party keeps heading right.

Nor is it tenable to argue that Republicans pay no electoral price because the Democrats have raced to the left as quickly as they’ve headed right. Figuring out exactly where parties stand isn’t easy. But widely respected measures of ideology based on congressional votes show Republicans moving much farther right than Democrats have moved left. (When you look at the positions that presidents take on congressional legislation, you also find that Democratic presidents have become more moderate even as Republican presidents have become more extreme.) While Democratic politicians have tacked left on some social issues — mostly where public opinion has, too — the party is arguably more moderate on many economic issues than it was a generation ago: friendlier to high finance, more venerating of markets, more cautious about taxes. It is the core of the Republican Party that has transformed. And yet, contrary to expectations that swing voters will punish them for their extremism at the polls, they just keep on going.

In a 50-50 nation, Republicans have learned how to have their extremist cake and eat it too. Figuring out how they’ve pulled off this feat is the key to understanding what has gone wrong with American politics — and how it might be fixed.

What Happened to the Median Voter?

That the Republican Party has grown more conservative is not exactly breaking news. Yet journalists routinely fail to point out just how significant the shift has been. When Senator Richard G. Lugar of Indiana was defeated by a tea party opponent in a GOP primary in 2012, commentators lamented the loss of “a collegial moderate who personified a gentler political era,” as the Times put it. Yet, as the political scientist David Karol rightly countered, what moderate? When Lugar joined the Senate in 1977, he was on the conservative end of the party — to the right not only of middle-of-the-road Republicans, but even relatively conservative senators such as Robert Dole and Ted Stevens. By the time of Lugar’s defeat, he was indeed at the moderate end of the party, but this had very little to do with any movement on Lugar’s part. The depiction of him as a “moderate” is akin to that eerie sensation you get when a train passes you while your train isn’t moving — scientists call it “vection.” The long-timers aren’t really moving left; they’re being left behind as their party moves right.

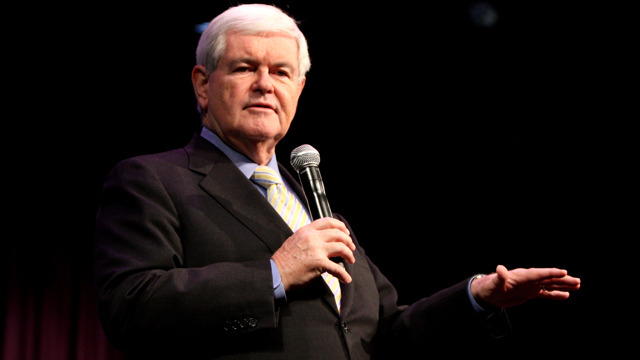

You feel political vection a lot these days. Newt Gingrich went from the right fringe of the party to the center before he was ousted from the leadership. John Boehner, now the Establishment pleader-in-chief, was significantly to the right of Gingrich when he entered Congress. Today, pundits wonder whether the “moderate” Jeb Bush can attract enough GOP conservatives to win the presidential nomination. (He might — presidential nominations are the one place where centrist GOP voters have some sway.) But when he started out in electoral politics in the 1990s, as Alec MacGillis recently wrote in The New Yorker, he was clearly on the conservative side of the GOP and to the right of his brother George. Jeb was a self-described “head-banging conservative” who said he would “club this government into submission.” He has mellowed a little, but mostly it’s that his party has gotten more hyper.

Today, mainstream Republicans denounce positions on health care, climate legislation and tax policy that were once mainstream within the party. Leading figures in the GOP embrace rhetorical themes — state nullification of federal laws, the wholesale elimination of cabinet departments, “makers” versus “takers” — that were only recently seen as beyond the pale. Under pressure to appear neutral and play up conflict, the news media like to focus on the divide at any moment between the GOP’s right fringe and its more moderate members. But look at American politics as a moving picture and you see an ongoing massive shift of the whole GOP (and, with it, the “center” of American politics) toward the anti-government fringe.

Newt Gingrich speaking at the Western Republican Leadership Conference in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo: Gage Skidmore/flickr CC 2.0)

To understand the puzzle that this raises for political analysts, it helps to be familiar with the most famous concept in American electoral studies: the median voter. The idea comes from the economist Anthony Downs, who in the 1950s drew on research about where stores were located relative to the distribution of consumers. Downs’s simple insight was that politicians in a two-party system have strong incentives to position themselves in the middle, right next to their opponents. The prediction looked pretty good in the age of Dwight Eisenhower and congressional bipartisanship and the “median voter theorem” was born.

The median voter theorem allowed for a reassuring conclusion: Politicians who win must be pursuing the preferences of the middle-of-the-road voter. In the “equilibrium” created by competitive elections, voter preferences and the aims of elected officials align. Thus politicians who persistently don’t do what the theorem predicts raise not one but two fundamental questions: Why do they head to the extremes? And how do they get away with it? In other words, you need both motive and opportunity to knock off the median voter.

The Proof Isn’t in the Pudding

The median voter theorem may seem ridiculous today. But, in fact, it lurks behind much of the commentary on elections in professional and popular publications. Implicit in the endless attempts to explain why swing voters side with Republicans is a simple assumption: Republicans are winning elections and so they must be doing what a majority of voters want. The proof of voter preferences is in the pudding of electoral results.

Consider the recent thoughtful commentary on the 2014 election by John B. Judis, the journalist who (along with Ruy Teixeira) gave Democrats the greatest hope that demographic and economic shifts heralded an “emerging Democratic majority.” In his new salvo, published in National Journal, Judis says the prospect of such a majority was an illusion. Republicans are not just pulling in the usual suspects: evangelicals, working-class whites, tea partiers. They’re also attracting the broader white middle class. These voters would “probably not vote for a Republican who was openly allied with the Religious Right,” says Judis. But they are “willing to support an antiabortion Republican” if that’s not the main selling point. Most important, while “not unbendingly opposed to government,” “they are worried about overspending and taxes” and hence willing to back the GOP.

Like most analysts, Judis starts with the unstated belief that if Republicans are winning, they must be reaching moderate voters with their policy stances. But that assumption is unwarranted. First, Judis passes quickly over an absolutely critical aspect of Republicans’ advantage — turnout. If everyone votes, the median voter is the typical American citizen. But not everyone votes, and turnout in midterm elections is particularly low (historically so in 2014). In the past, that did not matter as much as it does today. The midterm electorate has always been smaller, but it has not always been so disproportionately Republican. High-turnout voters, such as the aged, have increasingly sided with the GOP, while the young and minority voters in Teixeira and Judis’s “emerging Democratic majority” have the lowest turnout rates, especially in midterm years. This, in fact, is one explanation for Republicans’ big statehouse edge. Though not widely noted, governors are overwhelmingly elected in non-presidential-election years, when turnout is much lower, even across different groups. Only nine states hold gubernatorial elections alongside the presidential election.

And it’s not just turnout that drives a wedge between citizens’ preferences and election results. In the House, gerrymandering and the electorally inefficient distribution of Democratic voters (with high concentrations in urban areas) give the GOP a sizable structural advantage. In 2012, a high-turnout year, Mitt Romney received a majority of votes in 226 congressional districts versus Obama’s 209. In the Senate, the lean of low-population states toward the Republicans has a similar effect. The 54 Republicans in the Senate won their seats with fewer total votes across the last three elections than the 46 Democrats (who also represent a larger total population). This is another reason why the fortunes of the GOP are so different between congressional contests and the presidential race.

It’s also the beginning of an explanation for why individual Republicans have the motive and opportunity to move so far right. In many congressional districts and red states, GOP politicians need to worry first and foremost about primary challenges. For these Republicans, the district median voter is less important than the Republican median voter.

Still, this doesn’t explain why even extremely conservative Republicans don’t face challenges from moderates within the party (in contrast, Democrats are routinely challenged by other Democrats to their right). And it certainly doesn’t mean that the Republican Party faces no electoral risks from its members’ continuing rightward lurch. Parties are collective organizations that balance what’s good for their individual members with what’s good for the growth and survival of the whole. In theory, when individual Republicans adopt stances way to the right of the typical voter, the party brand is tarnished and candidates in contested races lose, especially at the presidential level. What makes the GOP shift so remarkable, and so harmful to the workings of American democracy, is that it has proved so sustainable.

To understand why, we must first figure out where the motive for heading right is coming from.

The Race to the Base

Conventional images of the two parties see them as symmetrical reflections of each other. But when it comes to the activist core of the parties, there is no comparison. The Republican base is larger, more intense, better organized and fueled by distinctive partisan media outlets that make those on the other side look like pale imitations. Strong liberals are often motivated primarily by one issue — the environment, say, or abortion, or minority rights. Strong conservatives tend to describe themselves as part of a broad effort to protect a way of life. Even during the George W. Bush presidency, liberals wanted Democratic Party leaders to take moderate positions and expressed a strong desire for compromise. Conservatives consistently indicate they want Republicans to take more conservative positions and never, ever compromise with opponents.

Not surprisingly, self-described conservatives also show up when it counts. Whatever the form of participation — voting, working for candidates, contributing to campaigns — the GOP base does more of it than any other group. At the same time, the ideological distance between the party’s most active voters and the rest of the party’s electorate is greater on the GOP side than the Democratic side. Democratic activists are moderate as well as liberal (and occasionally even conservative). Republican activists are much more consistently conservative, even compared with other elements of the GOP electoral coalition.

Nonetheless, the imbalance in prevalence and intensity between self-identified liberals and self-identified conservatives hasn’t changed much in 35 years — even as the role of the Republican base in American politics has changed dramatically. Something has happened that has given that base a greater weight and a greater focus on “Washington” as the central threat to American society.

Here, we need to turn our attention from the GOP’s most committed voters to the organized forces that have jet-propelled the GOP’s rightward trip. Even the most informed and active voters take their cues from organizations and elite figures they trust. (Indeed, there’s strong evidence that such voters are most likely to process information through an ideological lens.) The far right has built precisely the kind of organizations needed to turn diffuse and generalized support into focused activity on behalf of increasingly extreme candidates.

Those organized forces have two key elements: polarizing right-wing media and efforts by business and the very wealthy to backstop and bankroll GOP politics. Pundits like to point to surface similarities between partisan journalists on the left and right, but the differences in scale and organization are profound. The conservative side is massive; describing its counterpart on the left as modest would be an act of true generosity.

At the heart of the conservative outrage industry, of course, is Fox News. Fox’s role as an ideological platform is unparalleled in modern American history. Its leading hosts reach audiences that dwarf their competitors’. The network plays a dominant role for its audience that is unique. And Fox is also distinguished by extraordinarily tight connections to the Republican Party — linkages, again, that have no parallel among Democrats.

What’s most remarkable is that Fox is just the beginning. The other citadel of the conservative media empire is talk radio, and if cable news looks like a lopsided teeter-totter, talk radio is that teeter-totter with a 16-ton weight attached to the right-hand side. Conservative on-air minutes outnumber liberal ones by a ratio of at least 10 to 1, and all of the major nationally syndicated shows are conservative. Just the top three have a combined weekly audience of more than 30 million. Moreover, the number of talk radio stations has tripled in the last 15 years.

The impact of all this is difficult to calculate. After all, Republicans were moving right even before Fox came on the scene, and much of Fox’s audience consists of people who already have strong political views. Even so, a recent, innovative study by scholars at Emory and Stanford finds that Fox News exposure added 1.6 points to George W. Bush’s vote in the 2000 election — more than enough to cost Al Gore the presidency. And this excludes the impact of talk radio and Fox’s further expansion since 2000. Arguably, however, the bigger impact of conservative media is to increase and focus intensity within the Republican base, sending compelling messages that build audience trust while insulating that audience from contrary information.

Flanking conservative media is a vastly expanded political infrastructure advancing a right-wing economic agenda and rewarding politicians who maintain fealty to the cause. Some analysts have stressed divisions between Establishment and tea party wings. But while differing over tactics and a handful of issues, the two large networks dominating GOP finances — the Chamber of Commerce and the Karl Rove – led network, on the one hand, and the Koch brothers network, on the other — overlap and agree far more than they conflict. These networks have coordinated their efforts in recent general elections and now provide organizational and financial support on a scale that makes them virtual political parties in their own right. The Koch network alone has announced plans to raise nearly $1 billion for the 2016 elections.

In short, the Republican base generates an exceptionally strong gravitational pull, and that pull takes politicians much farther from the electoral center than do the comparatively weak forces on the left of the Democratic Party.

Shark Attacks and Voters

Republicans, then, have a strong motive to move right. And we have seen that they have greater opportunity to do so because of uneven turnout and favorable apportionment. Still, as Judis suggests, Republicans are winning over many centrist voters, including many who express positions on specific policy issues that are relatively moderate. How have Republicans managed to escape the iron law of the median voter theorem: move to the center or lose?

Part of the explanation is that electoral accountability is far from perfect. As the political scientists Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels have documented, politicians are often punished for things they do not control, such as weather and momentary economic shifts. Misplaced accountability is a vital issue in electoral democracies. Where voters systematically make major mistakes, accountability vanishes. And without accountability, politicians don’t have to worry so much about being responsive to voters.

Call it the “shark attack” problem. In July 1916, a series of shark attacks on the Jersey shore left four people dead and prompted a media frenzy. (Sixty years later, the events would become the basis for the movie Jaws.) Four months afterward, Woodrow Wilson ran for re-election. On the Jersey shore, his vote was down three points.

Political scientists have found many examples of the shark attack problem:

- Voters are often only dimly aware of the policy positions and legislative actions of politicians, and politicians can do many things to diminish what awareness they have. (UCLA’s Kathleen Bawn and her colleagues call this “the electoral blind spot.”)

- Voters often have a hard time distinguishing more moderate candidates from more extreme ones. The mainstream media’s horse-race orientation and strong incentive to maintain an appearance of neutrality often make journalists unwilling to describe one party or candidate as more extreme than the other.

- Voters make decisions on the basis of factors (such as the very recent performance of the economy) that are unrelated to the policy stances of politicians.

- Voters may be increasingly willing to support the candidate perceived to be on “their” team rather than the one whose policy positions are closer to their own.

- Given the intensity of the base, extremism may generate compensating support (in money, endorsements, or enthusiasm) that offsets any potential lost ground among moderates.

All these factors suggest that we shouldn’t assume — in the style of evolutionary biology — that Republicans are winning because they are a better fit with voters’ beliefs. But Judis is right about one thing: Voters are a lot more fed up with government. And here we come to another depressing fact about accountability in America’s distinctive political system: The anti-government party has a huge advantage.

Cracking the Code of American Politics

The shark story seems absurd, random and of limited relevance. But imagine what would happen if political actors could actually make shark attacks happen. And imagine if they could also have those attacks attributed to their opponents. Sounds preposterous, right? But our political institutions make something like this possible.

In a parliamentary system, legislative majorities govern and those majorities are accountable for the results. Voters know who is governing and how to reward and punish. Our political system instead combines increasingly well-organized, parliamentary-style parties with a division of governmental powers. That dispersal of authority simultaneously makes governing difficult and accountability murky. It also creates opportunities for a party that is willing to cripple the governing process to gain power. And over the past generation, a radicalizing GOP has done precisely that, making American politics ever more dysfunctional while largely avoiding accountability for its actions.

Indeed, the most distinctive and damaging feature of Republicans’ right turn is that they have steadily ramped up the scale, intensity and sophistication of their attacks on government and the party most closely associated with it. The legal scholar Mark Tushnet calls these tactics “constitutional hardball.” From between-census redistricting to open attempts at Democratic vote suppression, from repeated budget shutdowns to hostage-taking over the debt ceiling, from the routine use of the filibuster to block legislation and nominations to open attempts to cripple executive bodies already authorized by law, the GOP has become, in the apt words of Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein, “an insurgent outlier in American politics” — a party willing to tear down governance to gain larger majorities in government.

Appropriately for a party increasingly geared not to governing but to making governance impossible, the two leaders of this transformation were not in the White House but in Congress: Newt Gingrich and Mitch McConnell. Gingrich liked to describe himself as a “transformative figure” — and he was. His political genius was to sense that if voter anxieties and anger could be directed at government and the majority party that ostensibly ran it, power would come. Achieving this goal required simultaneously ratcheting up dysfunction and disgust while more sharply distinguishing the GOP as the anti-government party.

Gingrich and his allies adopted a posture of pure confrontation. The goal was to drag the Democrats into the mud, and if some mud got on the Republicans, well, they were the minority and, besides, they were not the party of Washington. In 1988, in a speech to the Heritage Foundation, Gingrich described a “civil war” with liberals that had to be fought “with a scale and a duration and a savagery that is only true of civil wars.” He meant it.

Fatefully, Gingrich also went to war with moderate Republicans. (His faction liked to joke that only two groups were against them: Democrats and Republicans.) He led a rebellion against the first Bush administration’s efforts to reach across the aisle, hobbling the president’s 1992 re-election campaign before it had even started. Once the elder Bush was out of the White House, it became even easier to pursue a strategy of uncompromising opposition and scandal-mongering. Obstruction and vituperation became a twofer. With a Democratic president, the Republican assault not only weakened an opponent but promoted the sentiment that politics and governance were distasteful. Association with “Washington” became increasingly toxic, and the Democrats were the party of Washington.

The second phase of Republicans’ anti-Washington strategy was engineered primarily by Mitch McConnell. Personally devoid of mass appeal, McConnell nonetheless has a rare understanding of the American voter. Early on in his leadership, he recognized that American political institutions create a unique challenge for voters. The complexity and opacity of the process — in which each policy initiative faces a grueling journey through multiple institutions that can easily turn into a death march — make it difficult to know how to attribute responsibility. Even reasonably attentive voters face a bewildering task of sorting out blame and credit.

McConnell fully embraced this opportunity after 2008. He organized the GOP caucus in a parliamentary fashion and worked to prevent individual party members from accepting compromise: “If [Obama] was for it,” “moderate” Senator George Voinovich explained, “we had to be against it.” Without Republican willingness to “play,” the imprimatur of bipartisanship was unavailable. Republicans could make the Democrats’ policy initiatives look partisan to voters and produce a pattern of gridlock and dysfunction that soured voters on government — and the party of government. American institutions, McConnell knew, gave Republicans a lot of capacity to impede governance without a lot of accountability.

On occasions, Republicans have overplayed their hand, as they did with the government shutdowns of 1995, the impeachment of Clinton in 1998, and the debt-ceiling debacle of 2011. But the GOP has escaped blame for the general decline of effective government. What voters get is a sense that the system is a mess and Washington can do little about pressing problems. If voters place blame anywhere, it is as likely as not to fall on the pro- rather than the anti-government party and on the president, who is viewed as the country’s leader even if he has no capacity to pass laws or effectively promote bipartisanship when the GOP refuses to reciprocate.

Thus Judis is right to note that many moderately inclined Americans are now open to an anti-government message, fueled by their completely understandable distaste for contemporary Washington. This is not, however, because these voters have become more conservative. It reflects the GOP’s success in simultaneously activating and exploiting voter disgust. The deeper message of 2014 is that a radical GOP first drove government into the ditch, generating historically low approval ratings for Congress and then reaped the benefits.

In short, Republicans have found a serious flaw in the code of American democracy. What they have learned is that our distinctive political system — abetted by often-feckless news media — gives an extreme anti-government party with a willingness to cripple governance an enormous edge. Republicans have increasingly united two potent forms of anti-statism: ideological and tactical. And they have found that the whole is much greater than the sum of the parts.

Disrupting the Doomsday Machine

By now, reform-minded commentators have offered every manner of political fix for our present political dysfunction. Some are silly — getting members of Congress to hang out after hours isn’t going to bring back a relatively moderate GOP. Others are sensible. Reducing the role of the filibuster would increase accountability, reduce gridlock and make government more effective. Many reforms that would increase turnout (especially in midterm years) would also reduce the rewards of extremism. But these reforms are unlikely to be enacted as long as Republicans are in a position to stop them.

That’s why we believe that the vicious cycle of dysfunction, distrust, and extremism will require a long-term effort directed not just at formal rules but also at informal features of American politics. Republicans benefit from the decline of norms of moderation and fair play and from a deep public cynicism about government. To reverse the vicious cycle, Republicans have to be called out when they go too far, and voters need to be dissuaded from their anti-government skepticism and animus. These are Herculean challenges, but not insurmountable ones. The key is to start heading in the right direction now.

Despite the evidence of increasing Republican extremism, elite discourse — in journalism, academia and foundations — resists the notion that Republicans are primarily responsible for polarization and deadlock. To argue that one party is more to blame than another for political dysfunction is seen as evidence of bias, not to mention bad manners. Foundations will fund nonpartisan vote drives; they will not fund efforts to shame right-wing Republicans for crippling governance. Academics worry about seeming biased when the truly biased perspective is the one that treats the parties as equally extreme. And while Fox News takes an avowedly partisan line, most of the media world retreats into self-defeating denials of the truth that stares them in the face.

Consider what happened in 2013 when Mann and Ornstein, who had probably been the most quoted observers of Congress during the previous two decades, issued their well-documented critique, It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided with the New Politics of Extremism. The book emphasized the responsibility of the GOP for government dysfunction. After it came out, the authors were not quoted in the press or invited to the public affairs shows on which they had regularly appeared. As Mann explained, “I can no longer be a source in a news story in The Wall Street Journal or the Times or the Post because people now think I’ve made the case for the Democrats and therefore I’ll have to be balanced with a Republican.”

Balance is one thing when you are talking about ideological differences; it is dangerous when you are talking about basic facts of American political life. In too many crucial venues, the mainstream media’s desire to maintain the appearance of neutrality trumps the real need for truth-telling. The inevitable complexity of the governing process further increases the temptation to offer narratives that do not help more casual observers of our politics to determine accountability. This isn’t just bad journalism; it’s a green light for extremism.

Nowhere is this more true than with regard to the extreme anti-government tactics that have become such a central part of the GOP strategic repertoire. American political leaders in the past refrained from playing constitutional hardball not because it was legally impossible but because it was normatively suspect. Those norms were costly to breach; violators were subject to both public and private censure. Today, however, the price of hardball is effectively zero. For Republicans, indeed, it is often less than zero because the GOP gains so much from political dysfunction. Raising the price of these tactics requires opinion leaders to call out violations again. Journalists should treat partisan realities in the same way they should treat scientific disputes — by attending to the evidence.

Equally important, those who recognize the dangerous implications of extremism are going to have to make a concerted case for effective governance. Currently, Democrats are caught in a spiral of silence. No one defends government and government looks increasingly indefensible. Public life and government are seen as hopelessly gridlocked and corrupt, so they become more hopelessly gridlocked and corrupt. Even politicians who know that government has a vital role to play in making our society stronger have little incentive to make what is now an unpopular and unfamiliar case. Consider the almost complete silence of Democrats about the Affordable Care Act — a law that despite its limitations has unquestionably delivered considerable benefits to the majority of Americans. A 2014 study found that spending on anti-Obamacare ads since 2010 outpaced money spent for ads defending the law 15 to 1. No wonder public opinion remains doubtful even as actual results of the law look more positive.

As difficult as it surely will be, there is no substitute for restoring some measure of public and elite respect for government’s enormous role in making society richer, healthier, fairer, better educatedan and safer. To do that requires encouraging public officials to refine and express that case and rewarding them when they do so. And it requires designing policies not to hide the role of government, but to make it both visible and popular. A tax cut that almost nobody sees, and which those who do see fail to recognize as public largesse, will make some Americans richer. It will not make them more trusting of government.

We are under no illusion about how easily or quickly our lopsided politics can be righted. But put yourself in the shoes of an early 1970s conservative and ask how likely the great right migration seemed then, when Richard Nixon was proposing a guaranteed income and national health insurance and backing environmental regulations and the largest expansion of Social Security in its history. Reversals of powerfully rooted trends that threaten our democracy take time, effort and persistence. Yet above all they require a clear recognition of what has gone wrong.