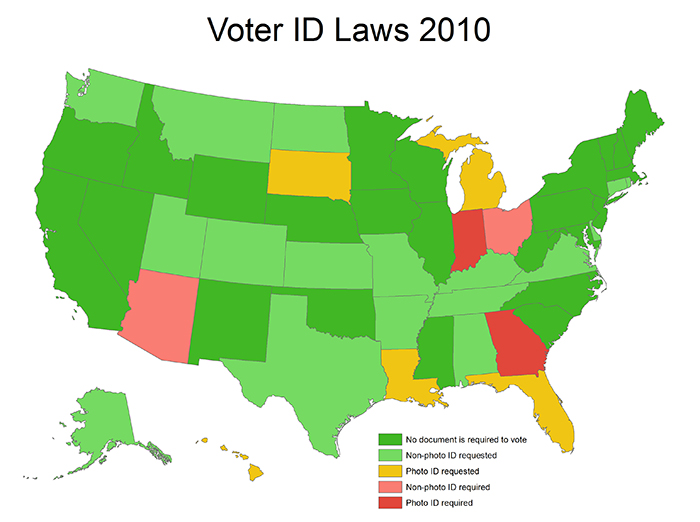

In only two additional states, Arizona and Ohio, some ID — whether a photo ID or one showing a name and address — was absolutely required. Of those states with an ID requirement, many were like Louisiana, which allows a voter without an ID to cast a ballot after signing an affidavit swearing to their identity.

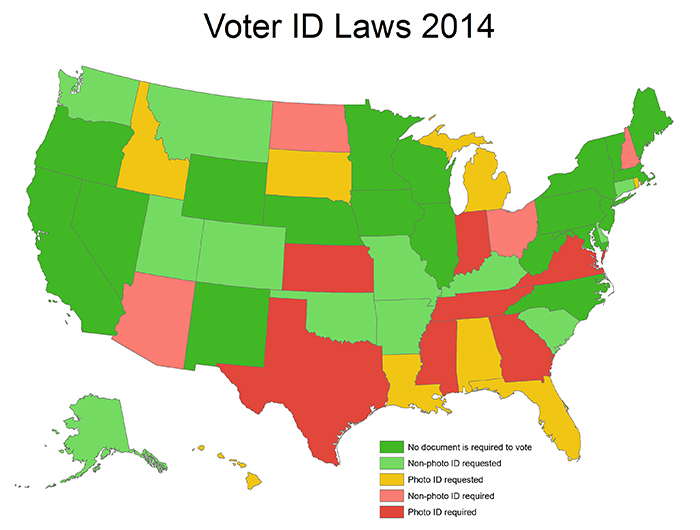

But since 2010, 16 states have passed laws relating to voter ID requirements and 11 states now have, or will have in upcoming elections, what are considered “strict” voter identification requirements.

What’s at stake is how we define our democracy — who can participate and who will be kept out of the electorate. For voters without a photo ID, obtaining one can be nearly impossible, as in the case of Alberta Currie who was born at home and doesn’t have a birth certificate.

Or it can be too costly, as in the case of Sammie Louise Bates, who testified that faced with the choice of paying for the documents needed to get an ID, or buying food, she chose food because “we couldn’t eat the birth certificate.”

Several of these new laws were either passed or put into effect after the Supreme Court decided the Shelby County v. Holder case in 2013, ruling that portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 are unconstitutional.

For five decades, the VRA gave the federal government the power to review voter-ID requirements from 16 states covered by the preclearance provisions of the act. Those provisions required every change affecting voting in those states to be reviewed (or “precleared”) by the US Department of Justice or a federal court before they could be put into place. If the voting change had the purpose or effect of making minority voters worse off in terms of their participation in the political process, the DOJ could object and stop the change.

Back in 1994, the DOJ issued an objection barring Louisiana from imposing a strict photo-ID requirement on first time voters who registered by mail, on the grounds that blacks in Louisiana were four to five times less likely than whites to possess a drivers’ license or other form of photo ID. But when Louisiana became one of the first states to pass a general photo-ID requirement for all voters in 1997, the law was cleared by the DOJ because it included a signature alternative that permitted voters without an ID to cast a ballot.

In 2011 and 2012, the DOJ issued objections to voter-ID requirements in South Carolina and Texas under the VRA, but once the Supreme Court gutted the act’s protections, Texas immediately announced plans to implement its photo ID requirement. South Carolina changed its law to permit people to vote who have a “reasonable impediment” to obtaining a photo ID.

Lawsuits challenging photo-ID requirements have been vigorously fought in state and federal courts. The first challenge to a photo-ID requirement for voting was in Virginia in 1999. In that case, Virginia sought to carry out a pilot program requiring IDs in some precincts but not others. The state court enjoined its implementation on the grounds that it would result in different eligibility standards for voters depending on where they lived and because of the potential harm to voters who would lose their right to vote.

Since then, legal challenges have had mixed results. There have been seven cases challenging photo-ID requirements under state constitutions. In three states the laws have been declared unconstitutional (Arkansas, Missouri and Pennsylvania), while in four other states the laws have been upheld (Georgia, Indiana, Tennessee and Wisconsin). The Michigan Supreme Court issued an advisory opinion in 2007 finding that state’s photo-ID requirement passed constitutional muster in part because the statute explicitly allows a voter without an ID to sign an affidavit and vote. A state constitutional challenge to North Carolina’s strict voter-ID law, which does not allow an affidavit alternative, is scheduled to go to trial this July.

At the federal level, an early challenge to Indiana’s photo-ID law was unsuccessful, but in upholding the law, the US Supreme Court based its ruling on the fact that eligible voters without photo identification could cast provisional ballots that would be counted if they later sign an affidavit at the clerk’s office.

Georgia’s voter-ID law was ultimately upheld, with some modifications. Currently pending are federal lawsuits challenging voter-ID requirements in Texas, Wisconsin, North Carolina and, as of March 4, Tennessee. The plaintiffs in these cases make a number of constitutional arguments on behalf of those who are barred from voting under these laws.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.