This post first was published at Mother Jones.

Bottled-water drinkers, we have a problem: there’s a good chance that your water comes from California, a state experiencing the third driest year on record.

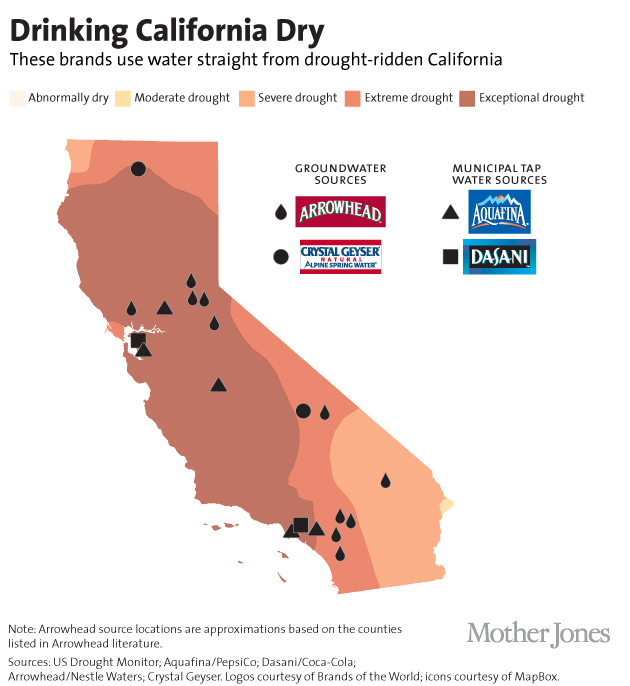

The details of where and how bottling companies get their water are often quite murky, but generally speaking, bottled water falls into two categories. The first is “spring water,” or groundwater that’s collected, according to the EPA, “at the point where water flows naturally to the earth’s surface or from a borehole that taps into the underground source.” About 55 percent of bottled water in the US is spring water, including Crystal Geyser and Arrowhead.

The other 45 percent comes from the municipal water supply, meaning that companies, including Aquafina and Dasani, simply treat tap water — the same stuff that comes out of your faucet at home — and bottle it up. (Weird, right?)

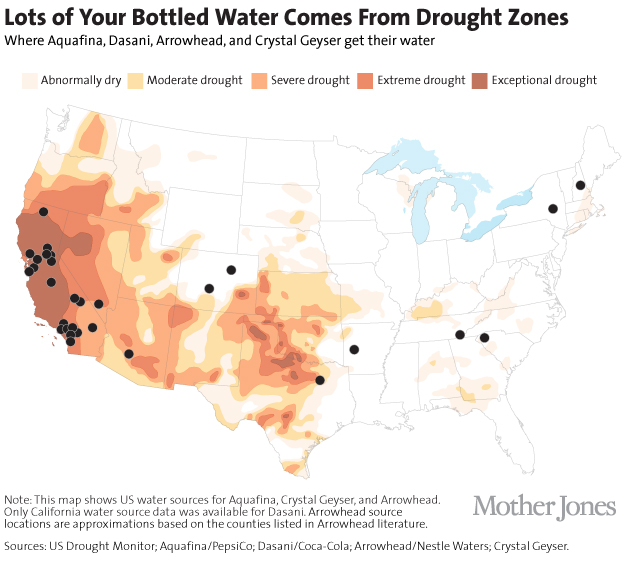

But regardless of whether companies bottle from springs or the tap, lots of them are using water in exactly the areas that need it most right now.

The map above shows the sources of water for four big-name companies that bottle in California. Aquafina and Dasani “sources” are the facilities where tap water is treated and bottled, whereas Crystal Geyser and Arrowhead “sources” refer to the springs themselves.

In the grand scheme of things, the amount of water used for bottling in California is only a tiny fraction of the amount of water used for food and beverage production—plenty of other bottled drinks use California’s water, and a whopping 80 percent of the state’s water supply goes towards agriculture. But still, the question remains: Why are Americans across the country drinking bottled water from drought-ridden California?

One reason is simply that California happens to be where some bottled water brands have set up shop. “You have to remember this is a 120-year-old brand,” said Jane Lazgin, a representative for Arrowhead. “Some of these sources have long, long been associated with the brand.” Lazgin acknowledges that, from an environmental perspective, “tap water is always the winner,” but says that the company tries to manage its springs sustainably. The water inside the bottle isn’t the only water that bottling companies require: Coca-Cola bottling plants, which produce Dasani, use 1.63 liters of water for every liter of beverage produced in California, according to Coca-Cola representative Dora Wong. “Our California facilities continue to seek ways to reduce overall water use,” she wrote in an email.

Another reason we’re drinking California’s water: California happens to be the only western state without groundwater regulation or management of major groundwater use. In other words, if you’re a water company and you drill down and find water in California, it’s all yours.

Then there’s the aforementioned murkiness of the industry: Companies aren’t required to publicly disclose exactly where their sources are or how much water each facility bottles. Peter Gleick, author of Bottled and Sold: The Story Behind Our Obsession with Bottled Water, says, “I don’t think people have a clue—no one knows” where their bottled water comes from. (Fun facts he’s discovered in his research: Everest water comes from Texas, Glacier Mountain comes from Ohio and only about a third of Poland Springs water comes from the actual Poland Spring, in Maine.)

Despite the fact that almost all US tap water is better regulated and monitored than bottled, and despite the hefty environmental footprint of the bottled water industry, perhaps the biggest reason that bottling companies are using water in drought zones is simply because we’re still providing a demand for it: In 2012 in the US alone, the industry produced about 10 billion gallons of bottled water, with sales revenues at 12 billion dollars.

As Gleick wrote, “This industry has very successfully turned a public resource into a private commodity.” And consumers — well, we’re drinking it up.