Congress hasn’t been this polarized in decades — since scholars developed objective methods of measuring lawmakers’ voting records. Twenty years ago, there was a significant number of Democrats who were more conservative than the most liberal Republican in Congress, and vice versa. Now there’s no ideological overlap between the two parties.

Political journalists often blame this sorry state of affairs on congressional “dysfunction” (while too often failing to note that Republicans have moved further to the right than Democrats have shifted to the left.)

But a new study by the Pew Research Center suggests that ordinary voters are almost as sharply divided as the lawmakers who represent them. The authors write, “Republicans and Democrats are more divided along ideological lines — and partisan antipathy is deeper and more extensive — than at any point in the last two decades. These trends manifest themselves in myriad ways, both in politics and in everyday life.”

That conclusion is based on “the largest study of US political attitudes ever undertaken by the Pew Research Center” — from January through March they interviewed more than 10,000 people.

This animated graphic, based on Pew surveys, shows that since 1994, voters — especially the most politically engaged — have moved away from the center.

According to the report, since 1994, the share of the electorate whose opinions are either consistently liberal or consistently conservative has doubled.

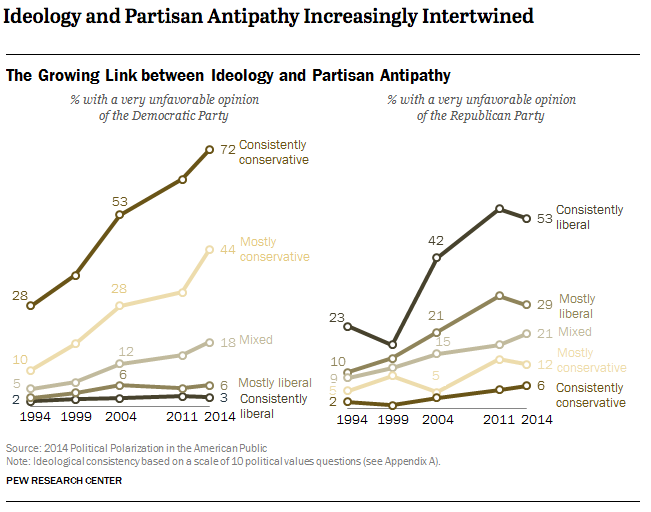

Partisan rancor has also increased — Democrats and Republicans really don’t like one another. But here we see differences between the parties — there are significantly more Republicans who think that Democrats are “a threat to the nation’s wellbeing” (36 percent) than there are Democrats who believe the same of Republicans (27 percent).

But there’s also a caveat here: When George W. Bush was in office, more Democrats than Republicans held a “very unfavorable view” of the other party, but that trend has reversed under Obama. So these views may be affected by which party controls the White House. Indeed, Pew finds that approval of presidents “in the opposing party have become steadily more negative” from the 1950s — when almost half of Democratic voters had a positive view of Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In any event, the study finds a strong link between ideology and antipathy toward the other party — being further out on the ideological spectrum is a pretty good predictor of how much distaste for the other party you’ll have.

Another area where the parties differ is in “political siloing” — the tendency to interact mostly with like-minded people. Significantly more “consistently conservative” voters (50 percent) say that it’s “important to live in a place where most people share my political views” than consistently liberal voters (35 percent). Similarly, 63 percent of staunch conservatives say most of their friends share their worldview, while 49 percent of liberals say the same.

That finding, according to Pew, is consistent with our increasing geographic separation, with conservatives drawn to suburban and exurban communities and liberals preferring densely populated cities.

As far as political gridlock goes, perhaps the most salient finding is that while those who aren’t highly engaged say politicians should meet in the middle on various issues, those who are more politically engaged — more likely to give candidates money, volunteer their time and vote in primaries — say they want lawmakers to “stick to their principles.”

Carroll Doherty, Pew’s director of political research, says that future studies will investigate possible causes for the widening divide among American voters — and which came first, hyper-polarized politicians or their constituents.

The Pew data is consistent with the conclusions of other studies. An in-depth report for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel found that city to be ideologically and geographically polarized — with both sides moving further apart in every election cycle. The University of Chicago’s Boris Shor and Princeton’s Nolan McCarty found that many state legislatures are now even more polarized than the US Congress — and that those divides also are growing wider. (The Sunlight Foundation has an interesting visualization of ideological polarization in state legislatures.)

Whatever the causes of this increasing political enmity between the parties, it’s making the country ungovernable. You can see that in Washington’s inability to address the foreclosure crisis or persistently high unemployment.

But it is good for one group of Americans. A study published last November in The Journal of Politics found that political gridlock correlates with the top 1 percent of households gaining a larger share of the nation’s income (BillMoyers.com spoke with one of the researchers about that finding in January). When politicians are at each other’s throats, it mostly hurts the middle class and the poor.