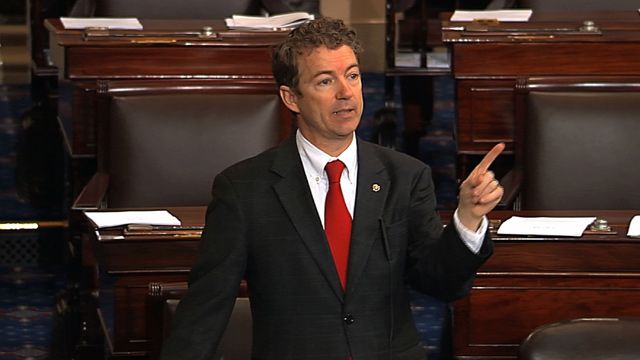

The Republican Party needs to broaden its appeal beyond whites, argues Rand Paul, who, as the Washington Post reported, is now organizing in all fifty states for a potential run at the presidency. No doubt he’s correct. But if the senator renowned for his libertarian principles is to spearhead this change, he has some political soul searching to do.

Speaking recently at UC Berkeley, Paul told the famously liberal audience that demographically the GOP must “evolve, adapt or die.” Seeming to take his own advice to heart, Paul also used the occasion — a talk on domestic surveillance — to chastise President Barack Obama for ignoring civil rights era lessons.

“I find it ironic that the first African-American president has, without compunction, allowed this vast exercise of raw power by the NSA,” Paul said. He explained, “J. Edgar Hoover’s illegal spying on Martin Luther King and others in the civil rights movement should give us all pause.”

If this were a one-off comment, it might seem like a cheap shot, but it’s part of a larger pattern of outreach. Paul spoke last year at the historically-black Howard University; has touted “economic freedom zones” in Detroit and is collaborating with Eric Holder, the nation’s first African-American attorney general, in order to reform prison sentencing practices that disproportionately harm blacks.

Nevertheless, when it comes to making his politics palatable to nonwhites, Paul faces deep challenges.

One problem — but not the biggest — is Paul’s close working relationships with racists. Back in 2009, Paul’s senate campaign spokesperson had a Myspace webpage that included a comment tied to the Martin Luther King holiday that read: “HAPPY N***ER DAY!!!” above a photo of a lynching. While someone else might have posted the comment, it remained on the staffer’s page for nearly two years.

Then in 2013, Jack Hunter, Paul’s social media director — and the co-author of Paul’s 2011 book on the tea party — was uncovered as the “Southern Avenger,” a radio shock jock who regularly donned a mask emblazoned with the Confederate flag and had a long history of making racially inflammatory statements, including praising Abraham Lincoln’s assassin for having his heart “in the right place.”

Under pressure, Paul reluctantly fired both offending parties — but did so while denying any racism on their parts. Back in 2009, he absolved his staffer of having “any racist tendencies,” while last year he protected Hunter for two weeks before finally letting him go and blaming the media. “He was unfairly treated by the media, and he was put up as target practice for people to say he was a racist, and none of that’s true,” Paul said. “None of it was racist.”

Beyond the problem of Paul’s close affiliation with these bigots, his inability to see them as racists suggests a huge blind spot with respect to racism — and this is a more fundamental problem, for this blinkered vision will make it almost impossible for Paul to grapple with how racial resentment fuels support for the libertarian politics he fervently espouses.

Paul presents overweening government power — especially at the federal level — as the paramount threat to ordinary Americans. If he is to popularize this message, though, Paul has to face an ugly fact: libertarianism has attracted substantial popular support not despite its occasional association with racists, but because of its ugly racial undertones.

Where white supremacists once commandeered government to enforce their appalling vision, the civil rights movement recruited government to promote integration. Government efforts to outlaw discrimination and to promote inclusion in schools, workplaces and neighborhoods became key to the effort to move the country toward racial equality.

But in response, libertarian ideas flourished, for anti-government rhetoric provided a seemingly neutral basis for opposing “race mixing.”

Pioneering this new use of libertarian rhetoric in his 1964 campaign, the Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater endorsed “states’ rights,” ostensibly a position on federal-state relations, though at the time all understood the target was federal efforts to push school integration. Goldwater also championed “freedom of association,” which purported to preserve the rights of property owners to exclude whom they wished, though in practice this meant the right of white establishments to bar minorities.

Today’s libertarian politics descends directly from this tradition. Illustrating the continuity, as recently as 2010, Paul himself endorsed the “freedom of association” argument, criticizing the 1964 Civil Rights Act for unjustly limiting the rights of private property owners. Paul put his position most succinctly in an earlier criticism of the Fair Housing Act: “A free society will abide unofficial, private discrimination — even when that means allowing hate-filled groups to exclude people based on the color of their skin.”

To his credit, Paul has since renounced those positions and frequently proclaims his opposition to racial discrimination. But as his responses to the controversies surrounding his staffers suggest, he still has a long way to go. Paul must grapple with why his small-government message resonates with so many whites — and if, for a sizeable number, the motive is a continued opposition to integration, then Paul must face this squarely if he is to craft a more inclusive party.