Take a moment, please, to note the passing of a distinguished spokesman for the left, a man both firebrand and gadfly, of whom many Americans have never even heard. Yet what he did and said are of importance to us all and especially to the cause of democracy.

Tony Benn died in London Friday morning, age 88. A diehard socialist once described by elements of the right wing in his country as the most dangerous man in Britain, The New York Times noted in its obituary that he was “the first peer to surrender an aristocratic title [in order] to remain in the House of Commons…

A rebellious scion of a political dynasty, Mr. Benn embraced a socialist position to the left of many of his colleagues in the Labour Party, particularly as it moved to the center under Prime Minister Tony Blair in the 1990s. While Britain’s political elite resisted and diluted union power, Mr. Benn championed labor union rights. While many Britons embraced the European Common Market in the 1970s, Mr. Benn opposed continued membership. And while Mr. Blair led the country to war in Iraq and elsewhere, Mr. Benn, a prominent advocate of nuclear disarmament, campaigned for peace.

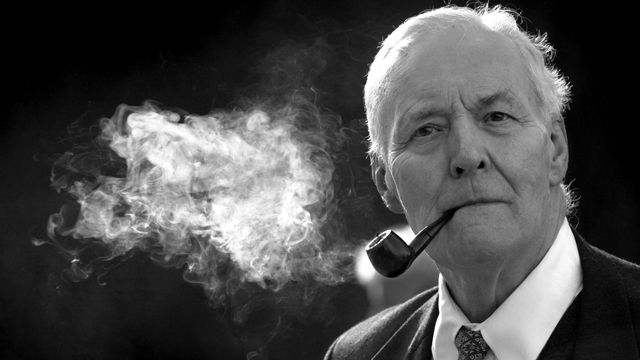

In this Oct. 3, 1967 photo, Tony Benn puffs on his pipe as he listens to speeches during the second day of the 66th annual Labour Party Conference, in Scarborough, England. (AP Photo/Laurence Harris, File)

“I think there are two ways in which people are controlled. First of all frighten people and secondly, demoralize them,” Benn told filmmaker Michael Moore. “… The people in debt become hopeless, and the hopeless people don’t vote.” Too many in power encourage such apathy and believe, he said, that “an educated, healthy and confident nation is harder to govern.”

Benn stood by his principles, even when they were damaging to his career and his party’s electoral ambitions. “Charming, persuasive and sometimes deeply frustrating,” is how former British Home Secretary David Blunkett described him to The Independent newspaper. “[But] what you would learn from Tony Benn was to think for yourself.”

He believed, like Dr. King, in that long arc of the moral universe that eventually bends toward justice. “How does progress occur?” he asked an interviewer from The Guardian in late October. “To begin with, if you come up with a radical idea it’s ignored. Then if you go on, you’re told it’s unrealistic. Then if you go on after that, you’re mad. Then if you go on saying it, you’re dangerous. Then there’s a pause and you can’t find anyone at the top who doesn’t claim to have been in favor of it in the first place.”Many remembered that as firmly as he held to his ideas — “a signpost and not a weathervane,” one recalled — he remained steadfastly courteous as well. Ian Dunt at the website politics.co.uk remembered watching Benn on television and hearing him say something “which fundamentally altered the way I saw the world.

He had just delivered a fierce speech in front of an admiring crowd. At the end he sat down on the stage, his legs dangling over the side, lit up his pipe and poured out a cup of tea from his thermos. A man approached him and explained that he was a Tory. He wanted to say something else, but Benn interrupted. ‘Oh, I do hope I haven’t said anything which upset you.’

He showed that politics, no matter how principled or drastic, did not need to be mean or cruel. Once again, he revealed the humanity within.

What I will always remember about Tony Benn is a sort of pop quiz he devised to put truth to power. He explained it in 2001, during his farewell speech to the House of Commons:

“In the course of my life I have developed five little democratic questions. If one meets a powerful person — Adolf Hitler, Joe Stalin or Bill Gates — ask them five questions: ‘What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interests do you exercise it? To whom are you accountable? And how can we get rid of you?’ If you cannot get rid of the people who govern you, you do not live in a democratic system.”

Anthony Wedgwood Benn, RIP.