This post originally appeared at ThinkProgress.

Anyone who has ever struggled to get her landlord to fix a broken appliance can imagine how much worse it could have been if she were paying rent to a faceless hedge fund based thousands of miles away. That tenant’s nightmare may be on its way to reality for hundreds of thousands of Americans, as Wall Street firms have snapped up 200,000 family houses with the intention of renting them out.

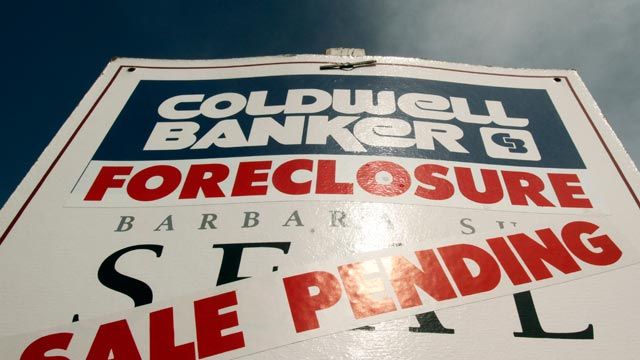

Banks, hedge funds and private equity firms have been amassing those real estate holdings for a few years now, but their plan for wringing profit out of the rental market is just starting to draw real scrutiny. The New York-based hedge fund Blackstone Group is now the nation’s largest landlord after purchasing over 40,000 foreclosed family homes for the purpose of renting them out.

While firms like Blackstone often farm out the day-to-day management of the rental properties to third-party companies, those intermediaries are often also based in faraway states. Some have a track record of being unresponsive to basic things like broken sewer pipes, as the Huffington Post has reported. The banks and their intermediaries may neglect basic upkeep of these properties. In that worst-case scenario for renters, local and attentive property managers and building supers will get replaced with “Wall Street-based absentee slumlords,” in David Dayen’s phrase.

On-the-ground concerns for communities and renters go beyond neglect, however. The rising influence of financial titans turned local landlords could threaten all sorts of public services. In the case of Huber Heights, OH, the hedge fund Magnetar Capital has become the largest landlord in the whole town and is using that influence to try to extract lower property tax charges from the town — a change that would undermine funding for schools and other public services for locals, but boost the bottom line of the Illinois-based financial giant. (Magnetar’s dodgy past dealings from the sub-prime era also underscore an unsettling dynamic to Wall Street’s entry into the rental market: the same companies that helped turn homeowners into renters through mass foreclosures are now preparing to make even more money off of the same rental demand they helped create.)

But firms like Blackstone aren’t just renting the homes, of course. The real money for the firm is in turning the rent payments it will receive from those 40,000 units into financial products called securities that it can sell to other investors. The practice could prove to be a broadly beneficial way to allocate scarce housing resources — or it could mirror the casino culture that turned the sub-prime bubble into an economy-wrecking conflagration.

With Wall Street buying up hundreds of rental properties and turning them into the same sort of complex investment products that caused the last financial crisis, Rep. Mark Takano (D-CA) thinks Congress has a responsibility to hold hearings and monitor the very new and potentially risky practices of this class of investor-landlords.

“Proper oversight of new financial innovations is key to ensuring we don’t go down the same road of the unchecked sub-prime mortgage backed security, and create an unsustainable bubble that will wreak havoc when it bursts,” Takano wrote Thursday in a letter to House Financial Services Committee (HFSC) Chairman Jeb Hensarling (R-TX) and Ranking Member Maxine Waters (D-CA). Magnetar staff declined to comment on Takano’s letter and Blackstone’s rental-backed securities.

Takano is right to worry that Blackstone’s new process of securitizing rent payments and selling them to all sorts of other investors puts the broader economy at risk. When Blackstone premiered its rental securities in November, it was able to get three credit ratings agencies to say that they are perfectly safe investments. But those agencies gave that same “AAA” stamp of approval to mortgage-backed assets that proved toxic in the last crisis. A fourth ratings agency, Fitch, was far more wary of Blackstone’s big new idea. Citing the “limited track record” of the idea and the untested nature of Blackstone’s landlord-cum-investment seller business model, Fitch said it was “too soon” to rate the firm’s security offering AAA.

That caution seems warranted. As Bloomberg explained in a thorough infographic, any significant problems in the rental housing market could quickly turn an investment in Blackstone’s scheme into a financial disaster. And it won’t just be other well-heeled financial companies that buy up this new set of rent-backed investment products, either. Pension funds, educational endowments, and other major institutional investors who rely on solid returns on their investment portfolio in order to fulfill promises to workers and students tend to get left holding the bag when financial schemes like this one go bad.

And problems in the rental housing market may be inevitable given that rents are rising far faster than family incomes. Nationwide, the number of people who face unaffordable rent prices is at an all-time high. A report put together by Takano’s staff demonstrates the shift from homeownership to renting amid rising rental costs within his Riverside County district. One third of all renters in Takano’s district spend more than half of their income on rent, a far higher rate than what financial professionals say is sustainable. The national rate is similar, the report says, with about 12 million of the nearly 41 million renter households nationwide paying more than half their income in rent. The median annual rent for Takano’s constituents is up $756 since 2007, but their median income remains about $5,500 below what it was prior to the crisis — another phenomenon that is common to the country as a whole.

Rents are rising in part because the years-long foreclosure crisis has meant that there are far more people in need of rental housing after having lost their homes. Thanks to that same foreclosure wave, hedge funds and private equity firms have been able to buy up 200,000 family homes at fire-sale prices, many of them in the Inland Empire zone of central California where Takano’s district lies. Citing these and other facts, Takano’s letter calls for a HFSC hearing to review developments in the rental housing market.

On top of the broader market factors driving rents up and keeping incomes from recovering, the supply of affordable housing is getting literally torn down as the housing industry focuses on building properties meant for middle- and high-income occupants. Given the building crisis in affordable housing and the impending threat of neglect from America’s new, inexperienced landlords, Takano’s call for oversight should be harder to ignore than the typical call to police Wall Street.

But a hearing on Wall Street investment schemes may be a tough sell given Chairman Hensarling’s past statements and actions with regard financial industry oversight, but the more localized damage that hedge fund landlords could do to individual renters on the ground might be more persuasive to the bank-friendly Texas Republican.