This post first appeared at In These Times.

Back in organized labor’s heyday, United Steelworkers (USW) Local 1010, in Hammond, Ind., decided to fight for pensions. It wasn’t a foolish notion. Some American workers had pensions, and new US labor laws and rulings had led the way to bargaining for them.

But there were companies that balked at the idea, and Inland Steel, which employed Local 1010 members, was one of them. So the steelworkers went on strike on Oct. 1, 1949. A month later, the strike was over, the local had a pension plan, and American workers gained a foothold on a ladder that they kept on climbing.

By 1980, pension plans covered nearly 36 million private-sector workers. Not all of these were union members. Once unions had pioneered pensions, non-union employers began offering these retirement plans as well.

For years, many pensions were of the “defined-benefit” variety, where employers set aside funds that were to be paid out to workers upon retirement. Workers put their faith and futures into these pensions, which were seen as an unbreakable promise that a lifetime’s work in even the dirtiest job would guarantee them senior years in comfort.

That began to change in the 1980s as the collapse of unions, financial crises, business failures and new accounting rules slashed away at these pensions. “Defined-contribution” pensions like 401(k)s were introduced, which shifted the financial burden and investment decisions to workers. They also lost the certainty that once came with traditional pensions. The transition has not gone well for some workers financially and emotionally.

By 2011, 31 percent of private-sector workers in the US had this new type of pension, while only three percent of workers were covered by defined-benefit plans, down from 28 percent in 1979, according to the most recent figures collected by the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a Washington, DC-based group.

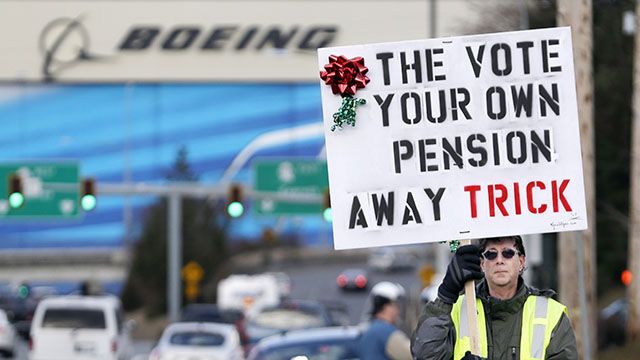

Last week, workers at Boeing became the latest group to say good-bye to these kinds of pensions. The workers’ furor over losing a traditional pension, a promise that had existed at the giant aircraft manufacturer since 1955, was a feature of the drama that played out for weeks and spread across the United States as Boeing dangled the possibility of moving high-paying factory jobs to a more business-friendly, less costly place, and drew bids from 22 states.

It was a reminder of the painful decisions unions face as they struggle to hold their ground and their jobs. Forced to choose between long-held contract gains and survival, many unions have backtracked, granting concessions and avoiding confrontations that they fear could backfire.

And it was a stunning display of a company’s determination to drive down labor costs amid incredible prosperity. Boeing was willing to dump its legacy in Washington state and its investment in its workers in order to find the best deal anywhere. Nowadays, such self-minded callousness is more and more common.

The battle over pensions began last year when Boeing approached the workers’ union at its factory in Washington, a 30,000-member local of the International Association of Machinists (IAM), and offered the chance to build its 777X jetliner, a state-of-the-art aircraft with carbon-fiber wings, if the union would negotiate a new contract.

But the company’s contract offer rattled the union’s members and cut deep divisions within its ranks. In November, the union rejected the company offer by a reported 2-to-1 margin. But the head of the union in Washington, DC, overruled the objections of local Machinists to order a re-vote. Last week, the offer passed by a slim margin, 51 to 49 percent.

The contract gives the workers at least some of what they wanted. That is, it promises to continue to build the new planes in the state of Washington. And it includes a $10,000 signing bonus for workers, along with an added $5,000 bonus to be handed out in January 2020, which the company threw in at the last minute to sweeten the deal. The company also agreed to drop a proposal that would have taken new workers 16 years to reach full pay rather than the current six.

But the eight-year extension comes with concessions for workers. It offers only modest wage increases, parceled out over time with one percent pay hikes every other year and cost of living raises annually. An eight-year contract also creates a burden for the union, limiting its ability to deal with changes with the company. (Typically, unions dislike such long contracts, which limit their actions, while companies increasingly prefer them because they provide financial and workplace security.)

Perhaps most painfully, when the contract takes effect in 2016, workers’ current defined-benefit pensions will be frozen, and they will switch over to a defined-contribution plan supported by the company. All new employees will receive defined-contribution pensions starting in 2016.

Rick Sloan, a spokesperson for the union’s international leadership, believes that these pension cuts were the sticking point for the workers when they initially rejected the contract. “Pensions was probably the issue for the ‘no’ vote,” he says.

But to the IAM leadership, there was a bigger, longer-term issue, Sloan says: jobs. If the machinists didn’t concede to the contract and Boeing carried through with its threat to move the 777X production out of Washington, the IAM stood to lose thousands of jobs. That would be a major blow to a manufacturing union that has seen its ranks dwindle as US factories have shed jobs precipitously over the past 40 years. In 2010, non-supervisory factory employment in the United States had sunk to 8.4 million, the lowest since 1939. The Machinists union has suffered accordingly steep losses, going from nearly one million members in the late 1970s to about 420,000 active members, according to Sloan.

That’s what worried IAM President R. Thomas Buffenbarger, who ordered the new vote after the local union officials refused to hold one, Sloan explains. But the heads of IAM District Lodge 751 were willing to face that risk, strongly urging their members in a letter to reject the proposal.

“We are faced then with a choice to destroy everything that we have built over 78 years in order to save Boeing from making a decision that puts the future of the company, all of its employees (union and non-union alike) and the stockholders at risk,” they wrote.

Usually when US companies have pressed for concessions, they have blamed their efforts on hard times. But Boeing relied on another explanation that has become popular: that it needs to keep costs down as it competes globally against fierce challengers. Caterpillar made a similar argument in the 1990s when it took on the United Auto Workers union and handily won the battle, allowing it to hire new workers at lower wages and disconnecting its contract from the pattern that the UAW traditionally set with the major US automakers.

In fact, Boeing has been doing exceptionally well lately, in financial terms: Its stock soared last year, and its chief executive, W. James McNerney Jr., reportedly received more than $27 million in total compensation in 2012, including a $4.4 million bonus for the company’s good performance.

The company’s very good health caught the attention of the union’s local leaders, who grumbled about them in their letter to members urging a “no” vote on the contract. Jake Rosenfeld, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Washington, agrees that there is a “disconnect” between the health of Boeing and the health of its workers. He views the disparity between Boeing’s prosperity and its wage-trimming and pension-cutting as a mark of a larger issue: the nation’s growing inequality.

While others might downplay the financial distress of Boeing machinists, many of whom reportedly earn about $70,000 a year before overtime pay, Rosenfeld disagrees. “These are the prototypical middle-class workers,” explained Rosenfeld, who is the author of an upcoming book, What Unions No Longer Do. Protecting these workers’ access to middle-class jobs and pensions, he suggested, is just as important to combating inequality as boosting the pay of low-wage workers.

By contrast, Jack VanDerhei, research director for the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI), which considers itself a nonpartisan group, views Boeing’s shift to defined-contribution pensions as part of a steady trend by businesses. For today’s workers, he says, the concept of a pension guaranteed after years on the job with one employer may no longer apply. Nowadays workers go from job to job, moving on after a few years. Likewise, companies have been increasingly loath to support such pensions because of accounting requirements, he said. (Under government rules, companies must set aside money for the pension funds, insure them and then keep them at the needed levels amid stock market and interest rate changes.)

Nor is he convinced that the worker-driven pension plans are as flawed as some claim. Workers who regularly contribute to their pensions and do not face disastrous stock market upheavals, can “wind up with the same or more” come retirement, he said.

But Leon Grunberg, a professor at the University of Puget Sound and the author of the 2010 book, Turbulence: Boeing and the State of American Workers and Managers, sees Boeing’s move as just the opposite of good business strategy.

Most business theory says that “you need a happy, well-committed workplace to have high profits,” explained Grunberg, whose book charts the lives of a large number of Boeing workers over the years.

And his study of the Boeing workers showed that “clearly the Boeing workforce is very unhappy,” he said. “But the shareholders, executives and stock analysts think things are doing well.”

For many Boeing workers and their supporters, however, the new Boeing contract boils down to something more simple: that uncertain futures have become a fact of life for US workers.