This post first appeared on HuffPost.

In this Jan. 25, 2006 file photo, Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), left, chats with Sen. Russ Feingold (D-WI) on Capitol Hill. (AP Photo/Lauren Victoria Burke, File)

Dysfunctional politics led a coalition of independent conservative groups and hardline Republican lawmakers to push for a showdown on Obamacareover a continuing resolution to fund the government and thus to shut down the government for more than two weeks. But what empowered a fracturing Republican Party to bring chaos on Washington?

The short answer: a one-two punch rewriting of campaign finance law that drove legislators to heed their own parties’ extreme elements.

Former Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-IL) has blamed the 2002 McCain-Feingold reform law, calling it “the worst thing that ever happened to Congress.” By taking unlimited “soft money” away from the political parties, but especially from the Republican Party, the law empowered the nascent insurgents at the Club for Growth.

President Barack Obama said it was the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision that “contributed to some of the problems we’re having in Washington right now.” Post-Citizens United, money from independent groups has poured into elections. Republican lawmakers who once held safe seats now worry about a primary challenge from the tea party right, funded in part by the Club for Growth, FreedomWorks or Heritage Foundation President Jim DeMint’s network.

But it’s the interaction between McCain-Feingold’s blow to political parties and Citizens United’s boost to independent groups that has really done the damage.

To be fair, campaign finance isn’t the only explanation for the crisis in Washington. Other reasons range from the abolition of earmarks to the increasing geographic ideological division of American voters. “The causes of polarization are extremely complex,” said University of California, Irvine, election law professor Rick Hasen.

Nonetheless, before they can clash over policy and budgets, members of Congress have to get elected and reelected. That’s how money can shift priorities.

The first of the two campaign finance upheavals came in 2002 with the McCain-Feingold law. The reform legislation stopped political parties from raising boatloads of soft money from corporations, unions and individuals and placed hard limits on contributions to political parties.

“Political parties have never been weaker than they are under the current system,” said Brian Walsh, former communications director for the National Republican Senatorial Committee.

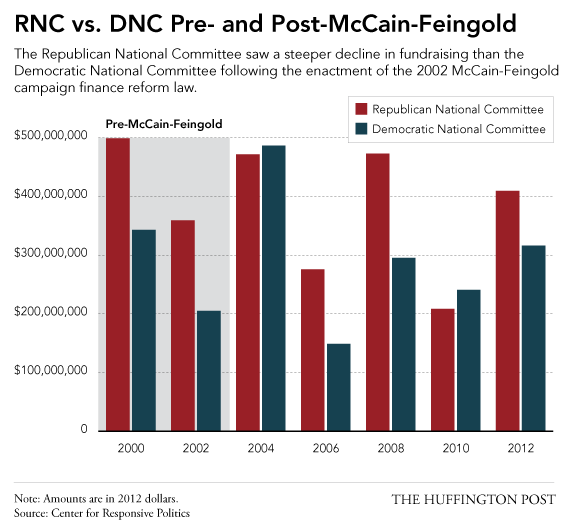

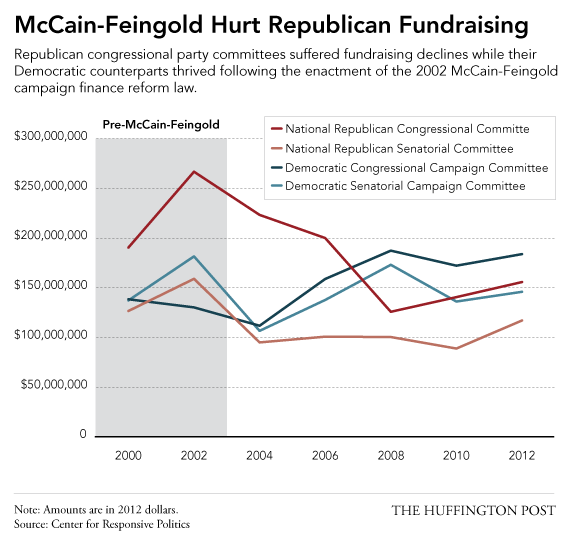

The fundraising numbers for the parties themselves bear this out to some degree, especially after the 2004 presidential campaign. Moreover, the Republicans’ congressional committees have seen a precipitous drop in fundraising while the Democrats’ congressional committees have seen an increase — in the case of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, a major increase. The Democrats did, however, start from a lower total pre-McCain-Feingold. (The numbers in the two McCain-Feingold charts have been adjusted for inflation to 2012 dollars.)

On the other hand, it’s not entirely clear what the Republican establishment could do with more money to control its rank and file or reel in its tea party rebels, whose frustration has been building for a while. Party efforts to defeat the more hardline candidates in its own primaries could well backfire to those candidates’ benefit.

“The current state of the Republican Party right now is that it could actually have a boomerang effect — speaking from my experience there, it would actually have a boomerang effect to spend money,” Walsh said.

Immediately after the passage of McCain-Feingold, independent nonprofits organized under Section 527 began to spend larger sums in elections. But there was significant uncertainty about the legality of this strategy, to the extent that these groups actually advocated for candidates. Then the Federal Election Commission levied historic fines on nearly every 527 group active in the 2004 election, including the Club for Growth’s 527 arm, for breaking campaign finance laws.

While McCain-Feingold reduced the amount of money raised by the Republican Party, it did not empower the intra-party insurgency. That came later.

The second major upheaval to campaign finance law occurred in 2010 with the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Citizens United v. FEC.

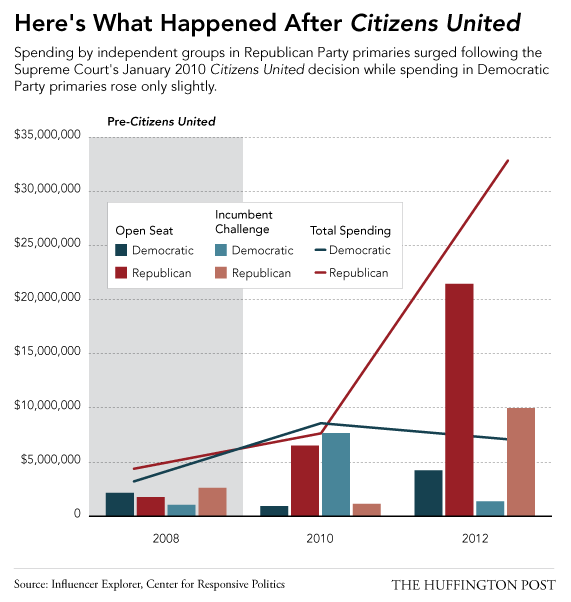

The Citizens United decision freed independent groups to spend unlimited sums on elections without worry of any regulatory backlash. A subsequent lower court case brought by the then-executive director of the Club for Growth expanded Citizens United’s reach and led directly to the creation of super PACs. Spending by independent groups surged immediately following these decisions and then exploded in 2012. This money surge was also visible in primaries, almost exclusively of the Republican variety.

Club for Growth spokesman Barney Keller said that changes in campaign finance laws have had nothing to do with its recent success in electing more conservative Republicans. “We’ve seen time in and time out that the amount of money spent in campaigns does not matter, but instead it’s the message. In every campaign we’ve been involved in, we’ve been outspent,” Keller said.

Hasen also said that while the increased threat of primary spending by independent groups is the best argument for a campaign finance effect on shutdown politics, it is likely the Republican Party’s internal battles were unavoidable. “The fight between the tea party groups started before Citizens United and likely would have happened under the old campaign finance rules,” he said.

But the money that Citizens United released made the voices of those tea party supporters much louder.

As Hastert told NPR, “It used to be they’re looking over their shoulders to see who their general [election] opponent is. Now they’re looking over their [shoulders] to see who their primary opponent is. … And so everybody’s kind of neurotic about where their support is.”

Campaign finance data shows that the majority of the independent spending in Republican primaries in 2012 came from the same insurgent groups behind the shutdown strategy: the Club for Growth, FreedomWorks, the Senate Conservatives Fund, Senate Conservatives Action and the Tea Party Express. These groups spent $17.9 million on last year’s primary campaigns or 54 percent of all money spent in Republican primaries.

That spending helped to elect a number of key players in Congress’ standoff, including leaders Sens. Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Mike Lee (R-UT). It also backed the Republican primary campaigns of Sens. Rand Paul (KY), Pat Toomey (PA), Marco Rubio (FL) and Ron Johnson (WI) and Reps. Thomas Massie (KY), Jim Bridenstine (OK), Ron DeSantis (FL), Matt Salmon (AZ), Justin Amash (MI), Kerry Bentivolio (MI) and Tom Graves (GA), among many others.

Those House members were also among the 80 congressional lawmakers who back in August signed a letter written by Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C.), with the help of FreedomWorks, urging House Republican leadership to adopt the very defund-Obamacare strategy that ultimately led to the shutdown. A number of the signatories had recently faced primary challenges heavily funded by that same list of conservative groups.

Rep. Paul Gosar (R-AZ) beat back a primary challenge funded by the Club for Growth in 2012. In 2010, the Club for Growth endorsed an unsuccessful primary opponent to and spent money against Rep. Chuck Fleischmann (R-TN). Rep. Richard Hudson (R-NC) faced a Club-backed candidate in his 2012 primary. All three signed Meadows’ defund letter.

The rise of tea party sentiments during the Great Recession created a ready base of support for those willing to take the hardest conservative line. It was the spending surge unleashed by the rewriting of campaign finance law, however, that made the congressional GOP listen so well.