This post first appeared at the Center for Responsive Politics’ Opensecrets.org.

On Oct. 8, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in McCutcheon v. FEC, a case challenging the overall contribution limits for individual donors that were first enacted in the mid-1970s.

The case won’t directly impact caps on contributions to specific candidates, party committees and PACs, which Congress put in place in order to ensure that a few people didn’t have undue influence on elected officials by being their dominant source of campaign funds.

But Congress also imposed overall limits on how much one person could give, in total, to all campaigns, PACs and parties during a single two-year election cycle; that’s the issue before the Court. Lawmakers recognized that without some global contribution boundaries, it would be possible for one or a few people to support lots of PACs or party committees that in turn would support one or a few campaigns. The theory was that the candidate would know the original source of all the funneled money and might feel obliged to reward that sugar daddy with official acts.

The limits are indexed for inflation; for the 2013-2014 election cycle, anyone can give a total of up to $123,200, with no more than $48,600 given to candidate committees and no more than $74,600 given to PACs and parties.

Now Shaun McCutcheon, a frequent contributor to Republicans and conservative causes, along with the Republican National Committee are trying to get the aggregate limits thrown out. They argue that the Court’s logic in Citizens United v. FEC — which said the bar on independent corporate election spending was a violation of First Amendment speech and association rights — should apply here, too. Restricting someone’s ability to support as many candidates or committees as he or she chooses, they argue, is no different than limiting the ability to spend money independently of a candidate or party.

What if the Court agrees? What would be the consequences if people could give the maximum contribution to as many candidates, parties and PACs as they wished?

The Center for Responsive Politics estimates that 1.2 million people gave contributions of $200 or more to presidential or congressional candidates during the 2012 election cycle. That’s a tiny fraction — 1/2 of 1 percent — of the total adult population of the U.S. These donors gave a total of $2.8 billion to federal candidates, party committees and leadership PACs; that’s about 64 percent of all of the funds raised by these organizations.

And these figures don’t include the ‘outside money’ that was such an important new feature in 2012 as a result of Citizens United and other court decisions. That’s a world with no limits at all, and not surprisingly it was even more skewed toward a small number of very big donors: Just 216 people gave about 68 percent of all the money that super PACs received. The limits don’t apply because these groups aren’t giving money to candidates or parties; they’re spending money themselves without coordinating with candidates.

The real focus of attention in this case is the (very small) group of people who were giving at or near the overall limit being challenged by McCutcheon. We found 646 people in the 2012 election cycle who hit the maximum overall donation limit of $117,000. This tiny group was able to give a total of about $93.4 million directly to candidates and committees active in federal campaigns.

The current overall contribution limit doesn’t appear to be much of a barrier for the vast majority of donors, or there would be many more people bumping up against it.

If the overall limits went by the wayside, would the specific limits on contributions that are not being challenged in this case ($2,600 per election per candidate from an individual, etc.) be enough to hold down the potential for corrupting influence on elected officials? Critics of McCutcheon’s position note that even with the aggregate limits in place, there’s been a steady growth in the use of both leadership PACs and joint fundraising committees in recent years, allowing big donors to maximize their interaction with specific elected officials who covet their resources.

Leadership PACs, which are created by members of Congress, give donors to party leaders and committee chairs another way to solidify those relationships. Contributors can give up to $5,000 per year to these committees on top of the $2,600 per election they can give directly to a member’s campaign. So these supporters can effectively double their financial ties to important members. Since 2002 the number of leadership PACs giving to other candidates has doubled from 226 in 2002 to 456 in 2012. Their contributions have risen from $25 million to more than $46 million during the same period.

Joint fundraising efforts allow candidates and parties to band together to share the proceeds of big events that draw wealthy donors. Important members of Congress will often team with national and state party committees for dinners and other events that allow donors intimate access to these leaders while effectively writing one big check to the joint committee. The money is divided among the candidates and parties involved to comply with the specific limits on each of the participants.

It’s a win-win situation for donors, who can make a big impression on elected officials, and parties, which can move lots of resources to the races that are their priorities — not to mention the candidates themselves.

All that’s keeping the number of zeros on these checks from running off the page are the overall contribution limits. Once a donor gets close to the $74,600 cap on contributions to all PACs and parties, or the $48,600 limit to all campaigns, tools like the joint fundraising committee are no longer able to pull more from the donor’s account.

Without those limits, tens of thousands could become hundreds of thousands and hundreds of thousands could turn into millions. Each individual could give at least $10,000 per year to party committees in every state, $32,400 per year to each national party committee (there are three of these for each party), and $5,000 per year to every PAC.

One of the first things that would surely happen without overall limits would be a wave of newly created PACs focused on specific candidate’s campaigns, which would allow donors to give $5,000 to any number of committees that would then give the money directly to the candidates.

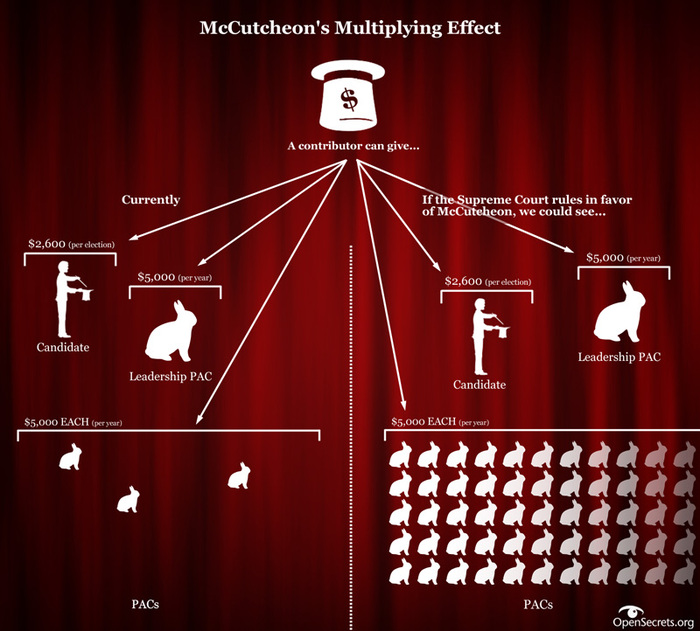

McCutcheon’s Multiplying Effect: Under current campaign finance law which limits not only how much an individual may give to a campaign or committee but how much can be given overall, there are only so many PACs a donor can give to every election. If the U.S. Supreme Court decides that an individual’s overall donations may not be capped, it won’t change how much a donor can give to a PAC, but it would allow donors to give to an unlimited number of PACs. This may cause the number of PACs to explode as each new PAC becomes an opportunity to collect more checks from donors. (Graphic by OpenSecrets.org/Hector Rivera)

Whether the overall limits are a good thing or not — and there are arguments on both sides — it’s clear that, if McCutcheon wins, people with lots of cash to invest in politicians would have a number of opportunities to direct money to a candidate. So much for $2,600 per election.

Individuals (as well as corporations and other entities, since the Citizens United decision in 2010) may currently give unlimited sums to outside groups that can spend without restriction in support of (or against) a candidate. Why isn’t it logical, then, to remove the cap on overall direct contributions to candidates and committees, as McCutcheon argues? Maybe it is, but if so, one of the basic premises of the Court’s first big campaign finance case would have to be rethought: the notion that direct contributions can lead to corruption, or at least its appearance. That’s why the Court in that 1976 case, Buckley v. Valeo, upheld caps on per-candidate and per-committee contributions.

Without an overall limit, though, those caps would lose much of their force.