This post originally appeared on The New York Times Economix blog.

Ten years ago this month, Congress enacted the third major tax cut of the George W. Bush administration. Its centerpiece was a huge cut in the tax rate on dividends. Historically, they had been taxed as ordinary income, but the Bush plan, enacted by a Republican Congress, cut that rate to 15 percent. The tax rate on ordinary income went as high as 35 percent.

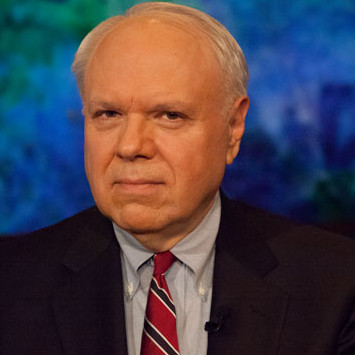

This initiative originated with the economist R. Glenn Hubbard, who had been chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers when the proposal was sent to Congress. Mr. Hubbard was a strong believer that the double taxation of corporate profits – first at the corporate level and again when paid out as dividends – was a major economic problem.

During the George H. W. Bush administration, Mr. Hubbard had been deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury for tax policy and wrote a Treasury report advocating full integration of the corporate and individual income taxes.

Mr. Hubbard had also spearheaded enactment of big tax cuts in 2001 and 2002 that he said would jump-start the American economy. In an op-ed article in The Washington Post on Nov. 16, 2001, he predicted that the soon-to-be-enacted 2002 tax cut, which President Bush signed on March 9, 2002, would “quickly deliver a boost to move the economy back toward its long-run growth path.”

Mr. Hubbard predicted that it would create 300,000 additional jobs in 2002 and add half a percentage point to the real gross domestic product growth rate.

There is no evidence that the tax cut had any such effect. The unemployment rate remained above 5.7 percent all year, rising to 5.9 percent in November and 6 percent in December. The real GDP growth rate fell each quarter of 2002, and by the fourth quarter growth was at a standstill. Hence the need for yet another big tax cut.

The idea of the 2003 legislation was to raise dividend payouts, thereby bolstering personal income, and raise the prices of common stock, which would improve household balance sheets. As President Bush explained in his signing statement, “This will encourage more companies to pay dividends, which in itself will not only be good for investors but will be a corporate reform measure.” He also said the dividend tax cut would “increase the wealth effect around America and help our markets.”

The Treasury Department issued a fact sheet on July 30 asserting that the decline in dividends had been a cause of the weak stock market and noting that dividend payouts had risen since enactment of the tax cut on May 28.

Subsequent research, however, found that the increase in dividends was a short-term phenomenon and mainly at companies where stock options were a major form of executive compensation. A 2005 Federal Reserve Board study found that the United States stock market did not outperform European stock markets after the dividend cut. Nor did stocks qualifying for lower dividend taxes outperform those, such as real estate investment trusts, that did not qualify for lower dividend taxes. Non-dividend paying stocks slightly outperformed dividend-paying stocks, and many corporations that did pay higher dividends scaled back stock repurchases by a similar amount.

Share repurchases were a common way that corporations returned profits to shareholders. They raised stock prices, which were untaxed as long as shareholders held the stock and were taxed at low capital gains tax rates when sold.

A 2006 Federal Reserve study found that a third of corporations cut share repurchases by the same amount they increased dividend payouts. Hence only the form of shareholder compensation changed, not the amount. A 2010 Federal Reserve study found little change in total dividend payouts after the 2003 rate cut as a percentage of corporate earnings. It concluded that the tax cut had little, if any, effect.

A 2008 study published in the National Tax Journal surveyed investment professionals to see their reaction to the dividend tax cut. It found that the tax cut was less significant than other factors, such as corporate cash flow and cash holdings that were unaffected by the tax change.

A 2011 study by the Treasury Department examined household portfolios. It found no evidence that households shifted their investments from those whose return was taxed as ordinary income into dividend-paying stocks whose income was taxed less.

Finally, a January 2013 study by Danny Yagan of the University of California, Berkeley, examined the impact of the 2003 tax cut on corporate investment. He found zero change.

It is hard to find even a reputable conservative economist willing to say anything good these days about President Bush’s tax and economic policies. In 2009, the Harvard economist Dale Jorgenson said he saw no redeeming features in them.

In 2011, the economist Alan Viard of the conservative American Enterprise Institute told Bloomberg News, “The effects of the Bush tax cuts on growth were ambiguous at best.” He added, “They were not much of a poster child for pro-growth tax policy.”

Even Mr. Hubbard now seems unwilling to defend the tax cuts he shepherded into law. Earlier this year, he was asked by The New York Times what he thought about the repeal of many of the Bush-era tax cuts on Jan. 1. He said many of those tax cuts were no longer relevant to our tax and economic problems.

Mr. Hubbard even suggested that higher revenues, long a Republican no-no, were not a bad thing. “We need a tax system that can promote economic growth and raise the revenue the American people want to devote to government,” he said.