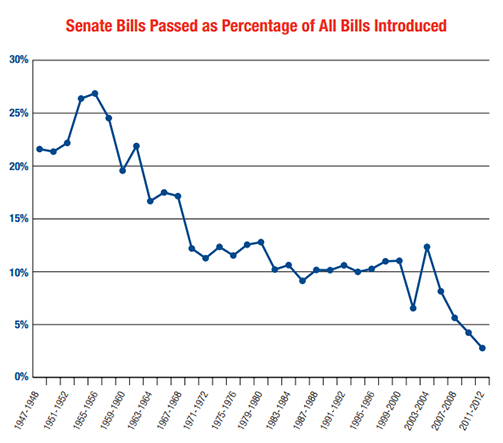

With the new 113th Congress comes the possibility of reform, but the just departed 112th Congress was historically unproductive. As shown in this chart from a November report by the Brennan Center for Justice, the Senate had passed a record low of 2.8 percent of all bills introduced.

(Brennan Center for Justice)

This impasse is largely created by filibusters, which are unique to the Senate, and have become so common as to create a situation in which to even be voted on nearly all major legislation requires a 60-vote supermajority, not the customary, 51-vote simple majority.

Here’s how that works: When a Senator decides to filibuster before a vote, he or she no longer has to stand and talk Mr. Smith Goes to Washington-style — the filibuster is now simply “procedural.” A Senator declares a filibuster, and can silently hold up discussion on a bill.

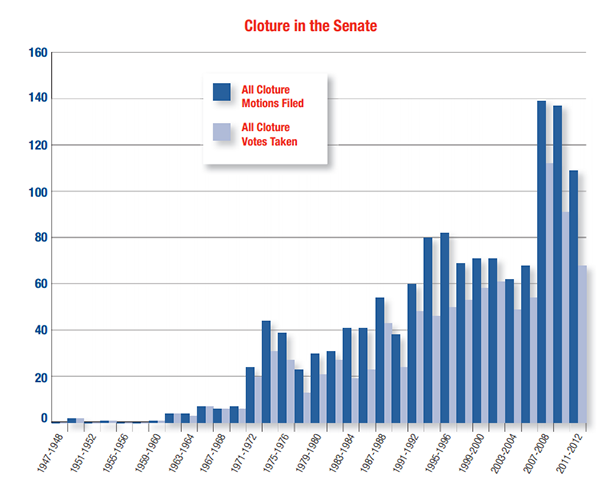

The only way to end a filibuster and move forward with a vote on a bill is through cloture, a motion to bring discussion — along with any filibusters holding up that discussion — to an end and then to proceed to a vote. Cloture requires a 60-vote supermajority to pass. In his article “Die, Filibuster, Die,” The New Republic editor Timothy Noah writes:

Today, cloture votes are so common that young people could be forgiven for believing the Constitution requires 60 votes for Senate passage of any bill.

Looking at the number of motions for cloture filed in a given Congress gives a rough sense of how much more time senators are spending on procedural motions instead of deliberating legislation. Since 2006, 385 cloture motions have been filed. That’s more than the number of clotures filed in the 70 years between 1917 (when the cloture was created) and 1988 (the last full year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency). But that’s not even the whole story. The mere threat of a filibuster can be enough to cause senators to abandon legislation or withdraw nominations.

(Brennan Center for Justice)