Silent march on Father’s Day to end the NYPD's stop-and-frisk policy in New York City on June 17, 2012. (Photo: Alan Greig/flickr CC 2.0)

This post originally appeared at Brennan Center For Justice.

Despite what many may claim, the United States is not in the midst of a nationwide crime wave. In fact, the average American can still enjoy some of the safest times on record. This is especially true in our largest city, New York, which also used to be one of our most dangerous. Given that history, it’s not surprising that New Yorkers carefully watch for any sign of an increase in crime, even while our city tops the list of safe large cities.

Most recently, journalists pointed to an increase in murder as renewed cause for concern in the Big Apple. Commentators are saying the uptick is only the beginning, in part because the city has wound down its controversial “stop-and-frisk” program, in which police stopped and searched citizens, allegedly without cause.

With stop-and-frisk over two years in the past, it’s an opportune time to evaluate that claim. The program’s end, it turns out, did not herald the start of a new citywide crime wave.

Stop-and-frisk became a central issue in the 2013 mayoral race because of a concern that the program unconstitutionally targeted communities of color. The program’s supporters disputed this, insisting that stop-and-frisk was essential for fighting crime in such a huge city.

Bill de Blasio, who won that 2013 mayoral election, campaigned on a promise to end stop-and-frisk. But, the courts nearly beat him to it. In August 2013, federal district court judge Shira Scheindlin found that stop-and-frisk had become a “policy of indirect racial profiling” and that the police had searched innocent people without any objective reason to suspect them of wrongdoing. Then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Raymond Kelly, the city’s police commissioner at the time, championed the program as a critical component of reducing murders and major crimes to historic lows. Bloomberg even sought to appeal Judge Scheindlin’s order, winning a temporary reprieve from the appeals court, and vowed to continue stop-and-frisk through the remaining four months of his term. “I wouldn’t want to be responsible for a lot of people dying,” Bloomberg said at the time.

The stop-and-frisk era formally drew to a close in January 2014, when newly-elected Mayor de Blasio settled the litigation and ended the program.

In the years leading up to the program’s official end, stops had already begun to plummet, leading article after article to claim that a jump in crime was just around the corner. All of the hard work of previous mayors and police chiefs could be undone, some said.

This alarm turned out to be both premature and incorrect, and data from the history of the program indicates this shouldn’t be much of a surprise.

After growing slowly in the early 2000s, stop-and-frisk began to rapidly increase in 2006, when there were 500,000 stops citywide. By 2011 the number peaked at 685,000. It then began to fall, first to 533,000 stops in 2012.

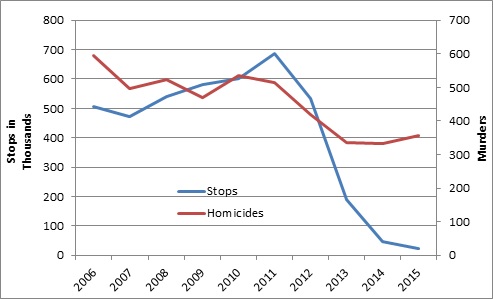

Given this large scale effort, one might expect crime generally, and murder specifically, to increase as stops tapered off between 2012 and 2014. Instead, as shown in Figure 1, the number of murders fell while the number of stops declined. Murder also continued to drop after stop-and-frisk wound down from its 2011 peak. In fact, the biggest fall in murder rates occurred precisely when the number of stops also fell by a large amount — in 2013.

Figure 1: Stops vs. Homicides in NYC (2006-2015)

(Source: NYCLU Stop-and-Frisk data and NYC CompStat)

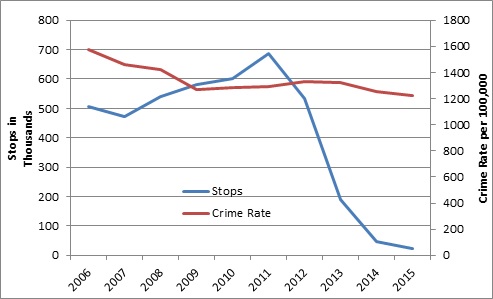

Figure 2 shows that crime in general also fell, both while the number of stops increased and fell. Crime continued to decline as the program wound to its 2014 close.

Figure 2: Stops vs. Crime in NYC (2006-2015)

(Source: NYCLU Stop-and-Frisk data and NYC Tcompstat.)

Statistically, no relationship between stop-and-frisk and crime seems apparent. New York remains safer than it was 5, 10 or 25 years ago. As analysis by the Brennan Center has shown, a part of this was the introduction of CompStat, which allowed police to consult data when making decisions about where and how to respond to crime.

Listening to the data has made New Yorkers safer, and it’s important to listen again. It says loud and clear: ending stop-and-frisk didn’t cause a crime wave in the city.