BILL MOYERS:

This week on Moyers and Company.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Money dominates politics. And as a result we have neither capitalism or democracy. We have some kind of -- we have crony capitalism.

BILL MOYERS:

And…

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

The big powered, moneyed institutions are in control in Washington, there's no doubt about it. You and I don't have a lobbyist and so we are not represented.

[Funders]

BILL MOYERS:

Welcome. This week we’re continuing our exploration of Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer and Turned its Back on the Middle Class. If you missed our first installment, you’ll find it at our website, BillMoyers.com.

Now this is only the second broadcast of our new series, yet we’ve already made our choice for the best headline of the month. Here it is:

"Citigroup Replaces JPMorgan as White House Chief of Staff."

Behind that headline is a tangled web.

The new chief of staff is Jack Lew. He used to work for the giant banking conglomerate Citigroup. His predecessor as chief of staff is Bill Daley, who used to work at the giant banking conglomerate JPMorgan Chase. Daley was maestro of the bank’s global lobbying and the chief liaison to the White House.

Bill Daley replaced Obama’s first chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, who once worked for a Wall Street firm where he was paid a reported $18.5 million in less than three years.

The new chief of staff, Jack Lew, comes from Obama’s Office of Management and Budget, where he replaced Peter Orszag, who now works as vice chairman for global banking at the giant conglomerate Citigroup. Still following me?

It’s startling the number of high-ranking Obama officials who have spun through the revolving door between the White House and the sacred halls of investment banking.

But remember, it was Bush and Cheney’s cronies in big business who helped walk us right into the blast furnace of financial meltdown. Then they rushed to save the banks with taxpayer money.

But of course, Bush and Cheney aren’t the only ones to have a soft spot for financiers. Bankers seem to come and go pretty frequently at the White House. President Obama may call them "fat cats" and stir the rabble against them with populist rhetoric when it serves his purpose, but after the fiscal fiasco, he allowed the culprits to escape virtually scot-free. And when he’s here in New York, he dines with them frequently and eagerly accepts their big contributions.

Like his predecessors, Obama’s administration has also provided the banks with billions of low-cost dollars they used for high-yielding investments to make big profits.

It's a fact. The largest banks are actually bigger than they were when he took office. And earned more in the first two-and-a-half years of his term than they did during the entire eight years of the Bush administration.

And get this: President Obama’s new best friend, according to The New York Times, is Robert Wolf. They play golf, basketball, and they talk economics when Wolf is not raising money for the President’s re-election campaign. Now, just who is Robert Wolf? Well, he's top dog at the U.S. branch of the giant Swiss bank UBS, the very bank that helped rich Americans evade taxes. Here, Senator Carl Levin describes some of the tricks used by UBS:

SENATOR LEVIN:

Here, Swiss bankers aided and abetted violations of U.S. tax law by traveling to this country with client code names, encrypted computers, counter-surveillance training, and all the rest of it, to enable U.S. residents to hide assets and money in Swiss accounts.

BILL MOYERS:

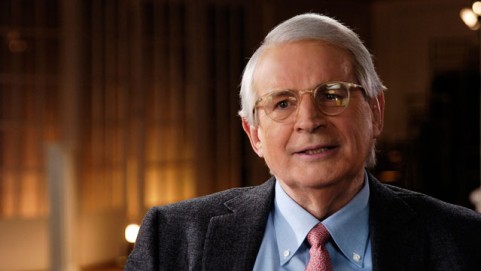

Quite a tangled web. One man who has strong views on all these cozy ties between Wall Street and Washington is David Stockman.

In the 1970s, he was a young Republican congressman from Michigan and an early proponent of supply-side economics -- some call it trickle down.

You know the theory; if you cut taxes on the wealthy, while cutting government, the economy will take off, money trickling down and creating millions of jobs.

It was the centerpiece of Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign for president.

RONALD REAGAN:

There is enough fat in the government in Washington that if it was rendered and made into soap, it would wash the world.

BILL MOYERS:

Once in the Oval Office, President Reagan made David Stockman his budget director.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

When President Reagan gave me this job he pointed to that budget which is some thousands and thousands of pages long, and he said go through it from top to bottom with a fine tooth comb and unless you can find a persuasive demonstration why funds must be spent, cut those budgets.

BILL MOYERS:

Stockman helped Reagan usher in the largest tax cut in U.S. history, a cut that mainly favored the rich. But things didn’t go exactly as they planned them. The economy sagged, and in 1982 and ’84, Reagan and Stockman agreed to tax increases.

In 1985 Stockman left government and wrote a book critical of his own years in power:

The Triumph of Politics: The Inside Story of the Reagan Revolution. He then took his economic expertise to Wall Street and became an investment banker. Thirty years later, he’s writing a new book, with the working title The Triumph of Crony Capitalism.

I sat down with him to talk about how politics and high finance have turned our economy into a private club for members only.

What do you mean by crony capitalism?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Crony capitalism is about the aggressive and proactive use of political resources, lobbying, campaign contributions, influence-peddling of one type or another to gain something from the governmental process that wouldn't otherwise be achievable in the market. And as the time has progressed over the last two or three decades, I think it's gotten much worse. Money dominates politics.

And as a result, we have neither capitalism or democracy. We have some kind of --

BILL MOYERS:

What do we have?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

We have crony capitalism, which is the worst. It's not a free market. There isn't risk taking in the sense that if you succeed, you keep your rewards, if you fail, you accept the consequences. Look what the bailout was in 2008.

There was clearly reckless, speculative behavior going on for years on Wall Street. And then when the consequence finally came, the Treasury stepped in and the Fed stepped in. Everything was bailed out and the game was restarted. And I think that was a huge mistake.

BILL MOYERS:

You write, quote, "During a few weeks in September and October 2008, American political democracy was fatally corrupted by a resounding display of expediency and raw power. Henceforth, the door would be wide open for the entire legion of Washington's K Street lobbies, reinforced by the campaign libations prodigiously dispensed by their affiliated political action committees, to relentlessly plunder the public purse." That's a pretty strong indictment.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Yeah and, but on the other hand, I think you would have to say it was fair. When you look at what came out of 2008, the only thing that came out of 2008 was a stabilization of these giant Wall Street banks. Nothing came out of 2008 that really helped Main Street. Nothing came out of 2008 that addressed our fundamental problems, that we've lost a huge swath of our middle class jobs. Nothing came out of 2008 that made financial discipline or fiscal discipline possible.

It was justified as sort of expediency. We need to do this. We need to stop the contagion. But it wasn't thought through as to what the long-term implications of this would be.

BILL MOYERS:

How did you see it playing out?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

I think there was a lot of panic going on in the Treasury Department. I call it "The Blackberry Panic." They were all looking at their Blackberries, and could see the price of Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley dropping by the hour. And somehow they thought that was thermostat telling them that the economy was coming unraveled.

I don’t believe that was right. I think what was going on was simply a huge correction that was overdue on Wall Street. The big leverage hedge funds on Wall Street that called themselves investment banks weren't really investment banks. They were just big trading operations using 30, 40 to one leverage. And it was that that was being corrected.

But they used the occasion of the Wall Street banking crisis to create the impression that this was the beginning of a kind of black hole the whole economy was going to drop into. I think that was wrong.

And it was that fear that led Congress to do anything they wanted. You know, the Congress gave them a blank check.

BILL MOYERS:

Not at first, don’t you remember, Congress first refused to approve the bailout, right?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

And then, the stock market dropped 600 points because all of the speculators on Wall Street all of a sudden began to think, "Hey, they might let capitalism work. They might let the rules of the free market function."

BILL MOYERS:

You mean by letting them fail.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Yes.

BILL MOYERS:

If they let them fail?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

I think if they let them fail it wouldn't have spread to the rest of the economy. There wouldn't have been another version of the Great Depression. There weren't going to be runs on the bank. We weren't going to have consumers lined up in St. Louis and Des Moines and elsewhere worried about their bank. That's why we have deposit insurance, the FDIC. But it would have been a big lesson to the speculators that you're not going to be propped up and bailed out,

You're not going to have the Fed as your friend. You're not going to have the Treasury with a lifeline. You're going to have to answer to the marketplace. And until we get that discipline back into our financial system, the banks are just going to continue to grow, continue to speculate and find new ways to make easy money at the expense of the system.

BILL MOYERS:

President Bush, he was still in office then.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Yes.

BILL MOYERS:

He said, I have to suspend the rules of the free market in order to save the free market.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

You can't save free enterprise by suspending the rules just at the hour they're needed. The rules are needed when it comes time to take losses. Gains are easy for people to realize. They're easy for people to capture. It's the rules of the game are most necessary when the losses have to occur because mistakes have been made, errors have been made, speculation has gone too far. The history has always been -- and this is why we had Glass-Steagall and a lot of the legislation in the 1930s.

BILL MOYERS:

Glass-Steagall was the provision --

DAVID STOCKMAN:

The division of banks between the commercial banking and investment banking and insurance and other --

BILL MOYERS:

So that you, the banker, could not take my deposits and gamble with them, right?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

That's exactly right. And we need not only a reinstitution of Glass-Steagall, but even a more serious limitation on banks. And what I mean by that is, that if we want to have a way for, you know, average Americans to save money without taking big risks and not be worried about the failure of their banking institution, then there can be some narrow banks who do nothing except take deposits, make long-term loans or short-term loans of a standard, business variety without trading anything, without getting into all of these exotic derivative instruments, without putting huge leverage on their balance sheet.

And we need to say simply, that if you're a bank and you want to have deposit insurance, which ultimately, you know, is backed up by the taxpayer -- if you're a bank and you want to have access to the so-called "discount window" of the Fed, the emergency lending, then you can't be in trading at all.

Now, on the other hand, if they want to be a hedge fund, then they’ve got to raise risk capital and they have to take the consequences of their risks, both to the good side and the bad side. And until we really approach that issue, and dismantle these giant, multi-trillion dollar balance sheet banks, and separate retail and deposit insured banking from just financial companies, we're going to have recurring bouts of what we had in 2008.

And they haven't even begun to address that, and it's so disappointing to see that the Obama administration, which in theory should've had more perspective on this than a Republican administration under Bush, to see that one, they appointed in the key positions the same people who brought the problem in: Geithner and Summers and all of those, and secondly, that Obama did nothing about it.

It could have easily -- they could have begun to dismantle a couple of these lame duck institutions, Citibank would have been a good place to start. But they did nothing. They passed Dodd-Frank, which said, now we're going to have everybody write regulations -- tens of thousands of pages that you know, it was a full employment act for accountants and lawyers and consultants and lobbyists. But they didn't go to the heart of the problem. If they're too big to fail, they're too big to exist. And let's start right with that proposition.

BILL MOYERS:

You've described what other people have called the financialization of the American economy, the growth in the size and the power of the financial industry. What does that term mean to you, financialization? And why should we care that it's happened?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Because what it means is that a massive amount of resources are being devoted, being allocated or being channeled into pure financial speculation that has no gain to society as a whole, has no real economic contribution to the process by which GNP is created, GDP is created and growth occurs.

By 2007 40 percent of all the profits in the American economy were coming from finance companies. 40 percent. Historically it was 15 percent.

So the financialization means that as we attracted more and more resources and capital, and we made speculation easier and easier, and we funded it with almost free overnight money, managed and manipulated by the Fed, that's how the economy got financialized. But that is a casino. Casinos -- they're, you know, places for people to go if they want to speculate and wager. But they're not part of a healthy, constructive economy.

BILL MOYERS:

What do you mean by the free money that banks are using overnight?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Well, by that we mean when the Fed, the Federal Reserve sets the so-called federal funds rate at ten basis points, where it is today, that more or less guarantees banks can go into the Fed window, the discount window, and borrow at ten basis points.

And then you take that money and you buy a government bond that is yielding two percent or three percent. Or buy some corporate bonds that are yielding five percent. Or if you want to really get aggressive, buy some Australian dollars that have been going up. Or buy some cotton futures. And this is really what has been going on in our markets.

The cheap funding, which is guaranteed by the Fed, the investment of that cheap funding into speculative assets and then pocketing the spread. And you can make huge amounts of money as long as the music doesn't stop. And when the music stops then all of a sudden, the cheap, overnight money dries up. This is what's happening in Europe today. This is what happened in 2008.

And then people are stuck with all these risky assets, and they can't fund them. They owe cash to the people they borrowed overnight from or on a weekly basis. That's what creates the so-called contagion. That's what creates the downward spiral. Now, unless we let those burn out, it'll be done over and over. In other words, if, you know, if a lesson isn't learned, then the error will be repeated over and over.

BILL MOYERS:

Stockman says the modern bailout culture took off under President Bill Clinton. It was engineered with the help of Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan and top economic advisors at the Treasury, Larry Summers and Robert Rubin.

BILL CLINTON:

The American people either didn’t agree or didn’t understand what in the world I’m up to in Mexico.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

I think it started with the bailout of the banks in 1994 during the Mexican Peso Crisis.

REPORTER:

For investors it was a sight for sore eyes.

Mexico’s stock market actually soaring instead of plummeting for the first time in weeks. All this, an immediate reaction to news of a major international aid package – nearly half of it from Washington.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

That was allegedly designed to help Mexico. It was $20 billion with no approval from Congress that was used, I think inappropriately out of a Treasury fund. And why were we doing this? It's because the big banks were too exposed to some bad loans that they had written in Mexico and elsewhere.

BILL MOYERS:

Wall Street banks. U.S. banks.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Wall Street banks. Wall Street banks. The banks of the day, Citibank, Bankers Trust, the others that existed at that time. And so the idea got started that Washington would be there with a prop, with a bailout, with a helping hand. And then the balls start rolling down the hill.

DAN RATHER:

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has taken highly unusual action to head off what could have been a severe blow to world economies.

BILL MOYERS:

When the hedge fund Long Term Capital Management blew up in 1998, it was big news.

REPORTER:

Dan, the Long Term Capital fund lost billions in the recent market turmoil and last night, stood on the brink of collapse.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Long Term Capital was an economic train wreck waiting to happen. It was leveraged 100 to one. It was in every kind of speculative investment known to man. In Russian equities, in Thailand bonds, and everything in between. And it was enabled by Wall Street.

REPORTER:

An emergency meeting was organized by the Federal Reserve last night, here at its New York office. At the table, more than a dozen of Wall Street’s biggest bankers and brokers including David Komansky, Chairman of Merrill Lynch, Sandy Weill of Travelers and Sandy Warner of JP Morgan. One by one the firms each agreed to kick in more than $250 million to bail out Long Term Capital before its troubles sent shockwaves through the banking system.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Why did the Fed step in, organize all the Wall Street banks, and kind of sponsor this bailout? Because all of the Wall Street banks that enabled Long Term Capital to grow to this giant size, to have 100 to one leverage, by loaning them money. So when the Treasury and the Fed stepped in and bailed out, effectively, Long Term Capital and their lenders, their enablers, it was another big sign that the rules of the game had changed and that institutions were becoming too big to fail.

Fast forward. We go through one percent interest rates at the Fed in the early 2000s, we go through the housing bubble and collapse.

BILL MOYERS:

Following the 2008 economic meltdown came the mother of all bailouts.

GEORGE W. BUSH:

Good morning. Secretary Paulson, Chairman Bernanke and Chairman Cox have briefed leaders on Capitol Hill on the urgent need for Congress to pass legislation approving the Federal government’s purchase of illiquid assets such as troubled mortgages from banks and other financial institutions.

BILL MOYERS:

The Bush administration came to the rescue of some of the county’s largest financial institutions, to the tune of 700 billion tax-payer dollars.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

We elect a new government because the public said, you know, "We're scared. We want a change." And who did we get? We got Larry Summers. We got the same guy who had been one of the original architects of the policy in the 1990s, the financialization policy, the too big to fail policy.

Who else did we get? We got Geithner as Secretary of the Treasury. He had been at the Fed in New York in October 2008 bailing out everybody in sight. General Electric got bailed out. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, all of the banks got bailed out, and the architect of that bailout then becomes the Secretary of the Treasury. So it's another signal to the financial markets that nothing ever changes. The cronies of capitalism are in charge of policy.

BILL MOYERS:

You name names in your writing. You identify several people as the embodiment of crony capitalism. Tell me about Jeffrey Immelt.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

He is the poster boy for crony capitalism. Here is GE, one of the six triple-A companies left in the United Sates, a massive, half-trillion dollar company, massive market capitalization. I'm talking about the eve of the crisis now, in September, 2008.

Suddenly, when the commercial paper market starts to destabilize and short-term rates went up. He calls up the Treasury secretary with an S.O.S., "I'm in trouble here. I need a lifeline." He had recklessly funded a lot of assets at General Electric Capital in the overnight commercial paper market. And suddenly needed a bailout from the Treasury. Within days, that bailout was granted.

And therefore, General Electric was able to avoid the consequence of its foolish lend long and borrow short policy. What they should have been required to do when the commercial paper market dried up -- that was the excuse. They should've been required to offer equity, sell stock at a highly discounted rate, dilute their shareholders, and raise the cash they need to pay off their commercial paper.

That would've been the capitalist way. That would've been the free market way of doing things. And in the future they would've been less likely to go back into this speculative mode of borrowing short and lending long. But when we get to the point where the one triple-A, a multi-hundred billion dollar company gets to call up the secretary, issue the S.O.S. sign and get $60 billion worth of guaranteed Federal Reserve and Treasury backup lines, then we are, you know, our system has been totally transformed. It is not a free market system. It is a system run by powerful, political and corporate forces.

BARACK OBAMA:

Thank you. Thank you.

BILL MOYERS:

So when you saw that President Obama had appointed Jeffrey Immelt, as the head of his Council on Jobs and Competitiveness, what went through your mind?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Well, I was in the middle of being very disgusted with what my own Republican Party had done and what Bush had done and the Paulson Treasury. And then when I saw this, I got the title for my book, “The Triumph of Crony Capitalism.”

BARACK OBAMA:

And I am so proud and pleased that Jeff has agreed to chair this panel, my Council on Jobs and Competitiveness, because we think GE has something to teach businesses all across America.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

If you have a former community organizer who was trained in the Saul Alinsky school of direct democracy, appointing the worst abuser, the worst abuser of crony capitalism, GE, who came in and begged for this bailout, to head his Jobs Council, when obviously GE's international corporation, they've been shifting jobs offshore for decades, then it becomes so obvious that we have a new kind of system, and that we have a real crisis.

BILL MOYERS:

Where is the shame? Shouldn't these people have been at least a little ashamed of running the economy and the financial system into the ditch and then saying, "Come lift me out?"

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Yes. You know, I think that's part of the problem. I started on Capitol Hill in 1970s. And as I can vividly recall, corporate leaders then at least were consistent. They might've complained

about big government, or they might've complained about the tax system.

But there wasn't an entitlement expectation that if financial turmoil or upheaval came along, that the Treasury, or the Federal Reserve, or the FDIC or someone would be there to back them up. That would've been considered, you know, it would've been considered, as you say, shameful.

And somehow, over the last 30 years, the corporate leadership of America has gotten so addicted to their stock price by the hour, by the day, by the week, that they're willing to support anything that might keep the game going and help the system in the short run avoid a hit to their stock price and to the value of their options. That's the real problem today. And as a result, there is no real political doctrine ideology left in the corporate community. They are simply pragmatists who will take anything they can find, and run with it.

BILL MOYERS:

So this is what you mean, when you say free markets are not free. They've been bought and paid for by large financial institutions.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Right. I don't think it's entirely a corruption of human nature. People have always been inconsistent and greedy.

But I think it's been the evolution of the political culture in which there have been so many bailouts, there has been so much abuse and misuse of government power for private ends and private gains, that now we have an entitled class in this country that is far worse than you know, remember the welfare queens that Ronald Reagan used to talk about?

We now have an entitled class of Wall Street financiers and of corporate CEOs who believe the government is there to do what is ever necessary if it involves tax relief, tax incentives, tax cuts, loan guarantees, Federal Reserve market intervention and stabilization. Whatever it takes in order to keep the game going and their stock price moving upward. That's where they are.

BILL MOYERS:

You were disaffected with the party of your youth, the Republican Party, because it has because -- it’s become dogmatic on so many of these issues and no longer listens to evidence and facts. I’m disaffected with the party of my youth because that Democratic Party served the interest of the working people in this country like Ruby and Henry Moyers. And so many people feel the same way. How do we overcome this pessimism about the American future? “The Wall Street Journal” had a headline on an op-ed piece that said, "The End of American Optimism." A recent survey said only 15 percent of the people were satisfied about the direction of the American people. I mean, this is a serious situation, is it not?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

I think it is. And -- but we also have to recognize the pessimism that the public reflects in the surveys and polls is warranted. In other words the public isn't being unduly pessimistic. It's not been overcome with some kind of a false wave of emotion. No. I think the American public sees very clearly the current system isn't working, that the Federal Reserve is basically working on behalf of Wall Street, not Main Street.

The Congress is owned lock, stock and barrel by one after another, after another special interest. And they logically say how can we expect, you know, anything good to come out of this kind of process that seems to be getting worse. So how do we turn that around? I think it's going to take, unfortunately a real crisis before maybe the decks can be cleared.

BILL MOYERS:

What would that look like?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

It will take something even more traumatic than we had in September 2008.

BILL MOYERS:

But on the basis of the record, the lessons of the past. The experience you have just recounted and are writing about. Do you see any early signs that we might turn the ship from the iceberg?

DAVID STOCKMAN:

No. I think we've learned no lessons. We really have not restructured our financial system. The big banks that existed then that were too big to fail are even bigger now. The top six banks then had seven trillion of assets, now they have nine or ten trillion.

Rather than go to the fundamentals which have been totally neglected-- we've simply kind of papered over the current system and continued the game of having the Federal Reserve and the Treasury if necessary prop up all of this leverage and speculation, which isn't helping the economy.

And when we talk about zero interest rates. That’s not helping Main Street. Our problem in this economy is not our interest rates are too high. The zero interest rates are just more fuel for leverage speculation for what’s called the carry trade and that is causing windfall benefits to the few but it’s leaving the fundamental problems of our economy in worse shape than they’ve ever been.

BILL MOYERS:

No one I know has a better understanding of the see-saw tension in our history between democracy and capitalism.

Capitalism, you accumulate wealth and make it available. Democracy being a brake, B-R-A-K-E, on the unbridled greed of capitalists. It seems to me that democracy has lost and that capitalism is triumphant -- crony capitalism in this case.

DAVID STOCKMAN:

And I think it's important to put the word crony capitalism on there. Because free-market capitalism is a different thing. True free-market capitalists never go to Washington with their hand out. True free-market capitalists running a bank do not expect that every time they make a foolish mistake or they get themselves too leveraged or they end up with too many risky assets that don't work out, they don't expect to go to the Federal Reserve and get some cheap or free money and go on as before.

They expect consequences, maybe even failure of their firm, certainly loss of their bonuses, maybe the loss of their jobs. So we don't have free-market capitalism left in this country anymore. We have everyone believing that if they can hire the right lobbyist, raise enough political action committee money, spend enough time prowling the halls of the Senate and the House and the office buildings, arguing for their parochial narrow interest -- that that is the way that will work out. And that is crony capitalism. It’s very dangerous and it seems to be becoming more embedded in our system.

BILL MOYERS:

So many people say, “We've got to get money out of politics.” Or as you said, “Money dominates government today.”

DAVID STOCKMAN:

Well look, I think the financial industry, over the two or three year run up to 2010 spent something like $600 million. Just the financial industry, the banks, the Wall Street houses and some hedge funds and others. Insurance companies. $600 million in campaign contributions or lobbying.

That is so disproportionate, because the average American today is struggling to make ends meet. Probably working extra hours in order, just to keep up with the cost of living, which is being driven up unfortunately by the Fed.

They don't have time to weigh into the political equation against the daily, hourly lobbying and pressuring and you know, influencing of the process. So it's asymmetrical. And how do we solve that? I think we can only solve it by -- and it'll take a constitutional amendment, so I don't say this lightly. But I think we have eliminate all contributions above $100 and get corporations out of politics entirely.

Ban corporations from campaign contributions or attempting to influence elections. Now, I know that runs into current free speech. So the only way around it is a constitutional amendment to cleanse our political system on a one-time basis from this enormously corrupting influence that has built up. And I think nothing is really going to change until we get money out of politics and do some radical things to change the way elections are financed and the way the process is influenced by organized money. If we don’t address that, then crony capitalism is here for the duration.

BILL MOYERS:

David Stockman, thank you very much for sharing this time with us.

One of journalism's premier business reporters is with me now. Gretchen Morgenson won the Pulitzer Prize for her fearless exposés of Wall Street's dirty secrets and reckless behavior. In her “Fair Game” column for The New York Times she digs into some of the most disturbing and complex scandals of our time. Her recent book with Joshua Rosner on crony capitalism at Fannie Mae is called Reckless Endangerment: How Outsized Ambition, Greed and Corruption Led to Economic Armageddon. Welcome.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Thanks, Bill.

BILL MOYERS:

You just heard David Stockman say it could happen again. Do you think it could happen again?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

It will happen again and the unfortunate fact is we did not fix the problem. The Dodd-Frank legislation which was supposed to be the fix-it for the enormous crisis that erupted in 2008 failed in so many ways to really address the major issues, the most important being too-big-to-fail, did virtually nothing to cut these big and impossible to manage banks down to size.

But there are other elements to the Dodd-Frank law that I think are also problematic. Now we have hundreds of rules being written by the regulators and although it might make sense that they know what they're doing a little bit more than maybe your, you know, average lawmaker, what it did was it gave the financial services industry two bites at the apple. They can lobby their lawmaker when Dodd-Frank is being written and now they are lobbying strenuously the regulators to make sure that the rules are written in a not too, you know, onerous fashion.

I mean, I think that you see this in the length of time, Bill, that it's taking to write these rules, tremendous jockeying back and forth by the financial services industry which of course has billions of dollars to spend on lobbyists to go and influence the outcome.

And so when you see, you know, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission trying to write rules about derivatives that would bring them into the open, that would make a failure like that almost brought AIG to its knees, make that a thing of the past you see a lot of the big Wall Street banks lobbying heavily to keep these things in the shadows.

BILL MOYERS:

Listening to both David Stockman and you, it. After what we've been through since 2008, the millions of lost jobs, the millions of foreclosed homes, the people whose pensions have been shrunk, you both are saying not only can it happen again, but it will happen again. I mean, I have to tell you it boggles my mind.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

When I was living through it, watching it in terror literally at my desk at The New York Times because it really was on the precipice, there we were, I thought to myself, "We will address this because this is so frightening and so scary and so damaging to this country." And I thought we will address it because this is the big one.

This is the big crisis that we've been leading up to. Long-Term Capital Management didn't really destabilize the system, the internet bubble didn't really destabilize the system, this was the big one. And yet the response was so lame and so ineffectual that it absolutely will happen again.

BILL MOYERS:

What's the answer? Why don't we have the reform we want?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Well, a big part of it is the money problem, that money -- the big powered, moneyed institutions are in control in Washington, there's no doubt about it. You and I don't have a lobbyist and so we are not represented in this melee, call it what you will, that happens, you know, when laws are created.

There is no balance here. There's a drastic imbalance between the people who created the problem and the people who had to pay the problem and it has not been addressed.

What David Stockman pointed out which is extremely important to remember in this whole thing is the rise of the financial institutions as a percentage of GDP in this country, as a percentage of as he said the resources that are put into this business. They have become all powerful.

These people have gotten themselves in such a position of power because they are financial intermediaries, because they are -- they affect every American with their business, they are able to much more than say the steel industry or the coal industry or the car industry manipulate the dialog. They can persuade the treasury secretary that, if you don't bail me out Armageddon is going to happen and everyday people will lose access to their money and the world will come to an end.

BILL MOYERS:

Right now we're hearing a lot about how Dodd-Frank is actually costing the banking industry. I think losing about $3 billion in the third quarter. Was Dodd-Frank responsible for that?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

I think that the small banks might have a point in that, in making that argument. The small banks that, by the way, did not create the problem, they're being penalized just like the Main Street people are because they have to now step up and do these new regulations that are quite costly for a small to midsize institution.

The big banks really don't have increased costs to that degree because they already have a huge compliance effort. They have a huge regulatory effort already. So it might be additional cost, but for them it's not as large as it would be for a small institution.

Again, this is the same imbalance, the same unfairness where a small institution that did nothing wrong now has to pay the price just like the taxpayers who did nothing wrong now have to pay the price while the big boys, you know, can complain about it, hire their lobbyists to do try to do something about it. I really discount a lot of the talk about how expensive Dodd-Frank is, particularly from these big institutions because they should really sit down and shut up.

BILL MOYERS:

Yes, I don't think they're going to but I think that's good advice. You do think as I do that Dodd-Frank is just too complex for effective enforcement, right?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Yes, you know that Glass-Steagall was 34 pages long.

BILL MOYERS:

34 pages?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

The act that protected Americans from rapacious bankers for almost 70 years was about 34 pages long.

BILL MOYERS:

And Dodd-Frank is 2,300 pages --

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Way too complicated, all kinds of loopholes, right? You know, the more complex a law is the more you can probably finagle around it.

BILL MOYERS:

Why should middle class people on Main Street care about how banks are regulated? What difference does it make to them?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

It makes a tremendous difference, Bill, because it affects every part of their lives. When they have to pay higher fees to get access to their money that's a cost they can ill afford. When banks are luring them into loans that are poisonous and toxic, that are designed to make the bank money and designed not to help the borrower, that is a real concern.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

It could not be more important to rein these institutions in because they affect every piece of your life. They affect your retirement, they affect your everyday expenses, whether you can put food on the table for your family.

They permeate your life, and so the degree to which they are making it more onerous to borrow is a huge -- has huge consequences.

BILL MOYERS:

Since you've been covering capitalism, business and finance what's been the biggest change you've seen?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Previously I believed that bankers that presided over this kind of a train wreck would have wandered away from the scene, tail between their legs, ashamed, or the regulators would have cleaned house, fired the management, clawed back their compensation.

We've seen none of that in 2008. Did the U.S. government replace any of these managements? No. Did the U.S. government claw back any of the money that these people made when the boom was going on which we now all know was a phony boom and so therefore that was phony money that they earned during those years.

We also didn't have a penalty, there were no penalties paid except by the innocent taxpayers. There were no penalties paid by the people who created the crisis.

BILL MOYERS:

Yeah, I read in one of your columns not too long ago that if a CEO is indicted, the penalties he may have to pay or even the cost of his lawyer -- he doesn't pay.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

The director's and officer's insurance often pays for these costs. The company many, many times pays for these costs. Angelo Mozilo is a perfect example, the former chief executive, co-founder of Countrywide, one of the most toxic lenders out there, really has created huge problems for especially minorities in this country.

He was charged with insider trading by the SEC, they settled the case. He didn't admit or deny guilt. All he paid was $22.5 million to civil penalties in the case. He sold stock worth more than $500 million over a period of years at the end of the boom. We are talking about a cost of doing business, something that he has no trouble paying. He happily wrote that check.

BILL MOYERS:

What do you think about the SEC's, the Securities and Exchange Commission's, performance since the meltdown?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

I think they have not been aggressive enough in going after compensation of these executives. I do think that they're understaffed, undermanned. They're always fighting for money.

They have gone after some very large insider trading cases, but again nothing to do with the crisis. There has been a resounding silence, Bill, from the prosecutorial function in this country to this crisis. There has been no one gone to jail from, that was really involved at a high level at one of these big mortgage companies.

BILL MOYERS:

What did you learn about crony capitalism in doing “Reckless Endangerment” based upon the mortgage industry business?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

What I learned was going back in time and examining Fannie Mae and as you know that's the company that doesn't make mortgages, but it buys mortgages and it guarantees them. So it is a huge player in this business.

That was really the quintessential crony capitalism, that company. They learned how to manipulate their regulator, to neutralize their regulator, to manipulate Congress, throw money around. They really told, almost showed Wall Street how to do it, they gave them a playbook. And what they did was they wrapped themselves in the American flag of home ownership so that they were impervious for many critics.

Fannie Mae, who used its implicit government guarantee for its own purposes, it was able to borrow money at a far cheaper rate than in any other financial company. And that subsidy, it took one third of that, billions of dollars every year, for itself.

So it really taught Wall Street how to be the quintessential, you know, crony capitalist. How to use your influence, how to use your money to buy protection for yourself on Capitol Hill and to manipulate the dialog so that there were no critics, no criticism of what you do, this whole idea of this financial services industry having to be protected.

Now, of course we know that Fannie and Freddie are into the taxpayer for $150 billion and no end in sight. So we know how that movie ends. And yet that is the practice and it continues.

BILL MOYERS:

The question is to me why don't we put those toxic twins, as you call them, out of business, close them down?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Well, because they're the only game in town right now for people who need to get a mortgage. And people need to get mortgages. They move, they get a new job. There does need to be the opportunity for movement in mortgage world and that’s -- they're the only game in town because banks are loathe to lend.

BILL MOYERS:

Without -- they’re loathe to lend our money back to us, right?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Correct. Absolutely.

BILL MOYERS:

Yeah, we bailed them out and they won’t put capital where it should go, to small businesses, to individuals who need it.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Absolutely, that's again here we are back at the same question. These people who drove us into the ditch, got our money to save themselves are now not lending to the degree that they ought to.

BILL MOYERS:

Which brings me to what you described in your column at the end of last year, the ugliest paradox of the financial crisis which you say became clear in 2011.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Well, as you know, Bill, we're only really starting to learn the full extent of what went on during the mortgage boom. But one element of it that I find especially troubling is the degree to which minority borrowers, first time borrowers, first time homeowners, immigrants, the least sophisticated people in this country, the very people that the government said they wanted to help become homeowners, to get their piece of the American dream -- those people were targeted by these banks because they knew they were unsophisticated.

They were targeted with the most expensive, the most punitive and the most toxic loans bar none. And to me that is such a failure of this country. If we are going to encourage home ownership, let's not do it on the backs of the very people that we are supposedly trying to help, the most vulnerable people in this country have been hurt the worst by this crisis, families wrecked, homes lost. They were abused in this entire mania and people profited from that abuse and I think that's wrong.

BILL MOYERS:

Well, as you know the pushback is, well, they shouldn't have been encouraged to buy a home, but they should have had the common sense not to buy a home without knowing more about what they were getting into.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

That's a good argument. But when you talk to people who English is their second language and when you talk to people who have never, you know, had an investment account, who really don't even maybe have a bank account and you've got some slick mortgage broker saying, "Oh, just sign here on the dotted line, everything's going to be fine," you can see how that goes awry. I mean, I’m a sophisticated person and, you know, I have to ask multiple questions if I’m looking at one of these mortgage documents.

BILL MOYERS:

What makes you angry about this?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

Well, it makes me angry because there has been no penalty. There has been no price for the people who created the mess. I thought there would be some sort of solution, some addressing of the problem, some punishment, penalty. Whatever you want to call it.

Now with the benefit of hindsight, you know, three, four years later nothing was done and so I am angry that nothing was done because that was one hell of a crisis and that was big enough for me, thank you very much, to learn the lesson of what we must do going forward to prevent another such thing.

And yet we didn't and that makes me angry because I have a son and he is going to live through this and he is going to pay the price for this. Not to mention, you know, everyday people who are going to live through it maybe within ten years. I don't think it's so far off that we're going to have another crisis.

It's really interesting, that we're still archeologists. I'm a journalist but I feel like I'm an archeologist digging in this crisis and still coming up with shards of pottery that I dust off and then I can fit into the puzzle. Because nobody wanted anyone to understand what really happened.

And there has been a tremendous, you know, attempt by the powers that be and I'm talking about the United States government, the Federal Reserve, the Treasury, banks, private institutions, as well, to prevent us from really learning the full extent of this. And so here we are, we're still uncovering things that we didn't know back in 2008, 2007. So no, I don't think anything significant has changed.

BILL MOYERS:

Is there anything you see that makes you a little optimistic?

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

What makes me optimistic is that people are understanding this now, that Main Street gets it, you know, the thing that I found compelling about the Occupy Wall Street movement was that it seemed to be tapping into this anger. Previous to that there was just this kind of silence, you know, people were maybe too flabbergasted by what had gone on.

This is a very complex crisis that was built over a long period of time. You have to connect the dots to understand it. And so we're writing history and helping people to understand what happened to them.

But we still don't know it all and until we do we can't really protect ourselves going forward. But I do get a sense that there is anger, that there is rage and that maybe, maybe, just maybe somebody in Washington might pay attention to that.

BILL MOYERS:

The book is Reckless Endangerment, Gretchen Morgenson with her colleague, Joshua Rosner. Thank you, Gretchen, for being with us.

GRETCHEN MORGENSON:

It is my pleasure, Bill.

BILL MOYERS:

That’s it for this week. When we continue our investigation of politically engineered inequality next week, you’ll meet John Reed, the bankers’ banker who was there when Washington closed its eyes to the Wall Street follies.

JOHN REED:

It wasn't that there was one or two or institutions that, you know, got carried away and did stupid things. It was, we all did. And then the whole system came down.

BILL MOYERS:

And former Senator Byron Dorgan, who saw it all coming.

BYRON DORGAN: (Speaking on the Senate Floor) And we are deliberately and certainly with this legislation moving towards inheriting much greater risk in our financial services industries.

BYRON DORGAN:

If you were to rank big mistakes in the history of this country, that was one of the bigger ones.

BILL MOYERS:

And check out our new website, BillMoyers.com. And read there an interview with Ellen Miller of the watchdog group the Sunlight Foundation.

See you online at BillMoyers.com, and see you here, next time.

Bill's Must-Read Money & Politics Books

Bill's Must-Read Money & Politics Books