This post first appeared at In These Times.

After Volkswagen issued a letter in September saying the company would not oppose an attempt by the United Auto Workers (UAW) to unionize its 1,600-worker Chattanooga, Tennessee, facility, Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN) was flabbergasted.

“For management to invite the UAW in is almost beyond belief,” Corker, who campaigned heavily for the plant’s construction during his tenure as mayor of Chattanooga, told the Associated Press. “They will become the object of many business school studies — and I’m a little worried could become a laughingstock in many ways — if they inflict this wound.”

Corker isn’t the only right-winger out to halt UAW’s campaign. In the absence of any overt anti-union offensive by Volkswagen, conservative political operatives worried about the UAW getting a foothold in the South have stepped into the fray.

Leaked documents obtained by In These Times, as well as interviews with a veteran anti-union consultant, indicate that a conservative group, Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform, appears to be pumping hundred of thousands of dollars into media and grassroots organizing in an effort to stop the union drive. In addition, the National Right-to-Work Legal Defense Foundation helped four anti-union workers in October file a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board claiming that Volkswagen was forcing a union on them.

“Everyone is definitely looking at this fight,” the anti-union consultant, Martin (not his real name), told In These Times. “This is the union fight going on right now and everybody [in the anti-union world] is looking to play their part and get compensated for playing their part.”

The last VW plant where workers don’t have a voice

As the only major VW plant in the United States, Chattanooga is also the only plant whose workers have no opportunity to join German-style “works councils” — committees of hourly and salaried employees who discuss management decisions, like which plant will make specific car models, on a local and global scale.

Organizing with the UAW, workers say, would help them to both form new works councils and gain representation at existing ones — which, in turn, would attract more jobs to the area.

“I personally feel like not having a union and not participating in a works council is going to do more damage for future expansion and new product development in Chattanooga than any unionization would do,” says Volkswagen employee Justin King. “The way VW works on the international level, [management] almost expects to work with a union. Now, we aren’t able to say, ‘Hey we would like to build that new SUV, or we would like to hire some new workers.’ We are only hurting ourselves by not going union.”

Workers also say having a union would help the plant be more efficient. “On the assembly line, the process changes each year because [of] new models,” says worker Chris Brown. “A voice in the company would help smooth the process from year to year.”

Beyond this, VW employees feel that organizing could help address their problems with corporate policy, including the fact that nearly one-fifth of workers at peak times in auto production have been temporary employees. Temporary employees’ starting wages are more than two dollars an hour lower than full-time employees’, and their healthcare and retirement benefits are much less robust, says the UAW.

According to Brown, approximately 200-300 “temps” are currently employed in the VW factory — and the UAW says they can remain classified as temporary even if they work at VW for years.

“I am friends with these people, and they want a job. Some of these people have been there for 18 months as a temp and that’s just … wrong,” says Brown. “If this is a job that I do, they should be making the pay that I make. [They] should have the same job security that I have as an employee.”

Fellow employee Lauren Feinauer agrees that a union would improve workers’ communication with management. “We heard a lot in the beginning about how VW works with their employees: close relationships and a lot of communication. I know there is a lot of that going on, but I think some of the VW way got lost in translation,” she says. “This is why we want a union.”

This September, the UAW announced that a majority of VW workers have signed up to join the union. But according to the UAW, it and VW still have yet to agree on a process for recognizing the union. That has left time for outside anti-union forces to try to dissuade workers from joining the UAW — time that many of those groups have capitalized upon.

Anti-union consultants get in the game

In a proposal dated Aug. 23, 2013, which was presented to a prominent anti-union group before being leaked to In These Times, Washington, DC-based consultant Matt Patterson outlined a vision of how anti-union forces can work with community groups to persuade VW workers that organizing is not in their long-term economic interest.

In the report, Patterson explained his approach thus far to laying the groundwork for an anti-union campaign, which he calls the “Keep Tennessee Free Project,” in Chattanooga. From last May to August, he said, he “leveraged a $4,000 budget into a deep and effective anti-UAW campaign that received national media attention, pressured politicians to issue public statements against unionization, forced the union to expend resources to counter our efforts, developed an extensive intelligence network that stretched from Chattanooga to Germany to Detroit and brought the terrible economic legacy of the UAW to the forefront of the debate.”

Patterson claimed that during the summer, he generated 63 stories denouncing the UAW effort in Chattanooga. In three months, he said, he was able to build a media echo chamber that now hammers Chattanooga with anti-union messaging on a regular basis.

And such remarks aren’t idle boasting. The fruits of Patterson’s anti-organizing crusade have appeared in the National Review, Forbes and local Chattanooga TV station WDEF 12, in addition to a host of smaller conservative talk radio shows.

But he didn’t stop there — he also gathered grassroots support. “Within a few weeks,” he wrote, “I had organized a coalition consisting of members of the tea party, Students for Liberty, former VW employees, politician and businessmen to craft and deliver a consistent message that has shaped public opinion.”

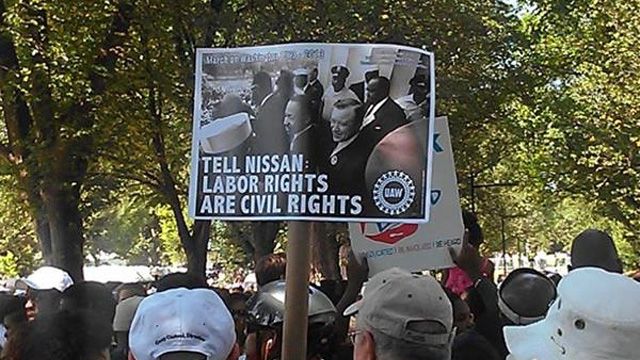

It’s clear that Patterson’s proposal was intended for an audience worried that a victory at Volkswagen could fuel UAW unionization campaigns at the Nissan plant in Canton, Miss., and at Mercedes-Benz in Vance, Alabama. “Based on the successes my coalition has already achieved, I am confident that with the request[ed] resources, significant impact can made be over the next year in Tennessee, Alabama and throughout the South to keep the UAW from organizing the foreign-owned auto facilities that are the source of so many badly needed jobs,” he assured possible funders.

According to veteran anti-union consultant Martin, Patterson originally asked for $160,000 in the proposal, which he sent to a variety of anti-union groups, including Martin’s. This, however, was before Patterson found a backer for his project: Americans for Tax Reform (ATR), the pet project of Republican mastermind Grover Norquist. Martin says that after Patterson decided to work with Americans for Tax Reform, his proposed budget rose “significantly.”

After the injection of new funds, Patterson’s voice in Chattanooga’s anti-union debate grew even louder. Local TV station WTVC News Channel 9 included him as an anti-union panelist in a televised Oct. 17 discussion about UAW organizing. Since September, Patterson has also been quoted by the Associated Press, Nashville Public Radio, the Chattanooga Times Free Press and even the Detroit Free Press, the UAW’s home turf newspaper.

Who’s funding the funder?

Martin says he’s uncertain of where the money for Patterson’s project is coming from, because Americans for Tax Reform is a 501(c)(4) that doesn’t have to disclose its donors. However, he finds this secrecy to be telling.

“It is definitely corporate money. It is obviously someone who doesn’t want it known who is doing this, and they have done a good job of covering it up, because I have absolutely no idea who is doing it,” he says. “It could be the local Chamber [of Commerce] trying to keep their fingerprint off of it. It could be Nissan seeing this is where they go to cut [unionization] off before it makes it way down to Mississippi.”

Or, as he points out, the funding could be coming from Volkswagen itself. Though it stated in September that it would not oppose the union, months later, the company has yet to announce how it will recognize the signatures the UAW has gathered from a majority of workers. Indeed, a top leader at VW recently proposed that workers should have to vote to unionize on a secret ballot in addition to signing what the UAW says are legally binding cards.

Furthermore, when speaking about VW’s statement of neutrality, Corker told the Associated Press, “There was a lot of dissension within the company … I don’t think it, I know it. Candidly, one board member got very involved and forced this letter to go out. I know that it’s created tremendous amounts of tension within the company.”

In an email to In These Times, Volkswagen spokesperson Carsten Krebs denied that the company was giving money to Patterson, but would not expand further on Volkswagen’s position on the union drive.

Republican dissent

In his frequent comments to the press, Corker has echoed Patterson’s assertion that unionization will limit job opportunities.

“If they see the UAW is building momentum in our state, other companies that are looking are not going to choose Tennessee [to settle in]; they’re just not,” an outraged Corker said in September.

In a high-profile interview with NPR in October, Corker continued, “I mean, look at Detroit. Look at what’s happened.” Referring to Chrysler and General Motors, he said, “Look at all of the businesses that have left there. I mean, it’s been phenomenal. It’s sad.”

However, not all Republicans are as alarmed by the prospect of the UAW entering the region. Sen. Saxby Chambliss (R-GA), whose district includes many VW workers who make the short commute across the border to Chattanooga, said in an interview at the Atlanta airport, “Honestly we have got a lot of employees that work up at the Volkswagen plant … You know I think one reason people are attracted to the South is that we are not heavily unionized, but we have got unions … I really had not thought too heavily about the VW plant, to tell you the truth.”

When asked in a follow-up question if having “one union plant threatens all the rest of the South,” Chambliss responded, “We have got a lot of union plants in the South … No, I don’t think it’s a problem.”

Workers under fire

Nevertheless, the amplification of the Patterson-Corker message in the local media is putting a great deal of pressure on VW workers in Chattanooga.

“I have had a lot of friends and neighbors come up and ask about me about the union,” says King. “Some of them come up and say it’s really great, but I have had a lot people come up to me and say, ‘You guys are idiots. You guys are going to bankrupt Volkswagen and shut the plant down.’ It definitely has turned into something that everyone has an opinion on.”

Brown says Corker’s statements have also turned some of his co-workers against the union in a plant where he says the overwhelming majority of the workers are Republicans.

“It does have an effect because this is a hardcore Republican area in the Deep South, and a lot of these people are Republicans, so what the party tells them is what they believe,” he says.

Martin tells In These Times that the campaign could get even more intense as other anti-union groups try to enter the conflict, including his own. In his opinion, Patterson’s campaign hasn’t been that sophisticated, mainly focusing on getting politicians to make statements and getting Patterson himself to appear regularly in the press—leaving plenty of room for other anti-union groups to join in the effort.

“It remains to be seen if [Patterson’s strategy] will be effective,” says Martin. “In the anti-union work that I have done in the past, we are far more surgical and high-tech … [Patterson’s campaign] is surprisingly unsophisticated. There is no web presence now, no Facebook, no Twitter — all the stuff that is usually typical in anti-union campaigns.”

In the meantime, VW workers think it’s unfair that outside forces are pressuring them.

“I find it disturbing that outside parties are trying to interfere with a decision that should rest solely with the company, the workers, and the UAW,” says Brown. “The Republican party is into government keeping its hands off of business, but in this instance they are seeing how deep they can get into it.”

King agrees that anti-union consultants and legislators don’t actually have VW employees’ interests at heart.

“I would invite any of the representative from these special interests or any of those politicians to come work for a few weeks in the factory and see how they feel about issue,” he says. “They should walk a few days in our shoes … A lot of people would feel different about it if they got more of a chance to talk to some of the Volkswagen employees.”

Full disclosure: The author’s mother worked on an auto assembly line at a VW plant in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, until it closed in 1988 and was a member of the UAW.