US border agents detain an undocumented immigrant caught near the US-Mexico border on March 13, 2017 in Roma, Texas. The Border Patrol has reported that illegal crossings from Mexico have dropped some 40 percent along the southwest border since Donald Trump took office. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

This post first appeared at Mother Jones.

Even though President Donald Trump continues to brag about the falling rate of unauthorized immigration across the US-Mexico border, a recent report from a United Nations-affiliated agency sheds light on a disturbing trend: The death rate at the border appears to be surging.

The report, released last week by the Missing Migrants Project, a division of the UN’s International Organization for Migration, says 239 bodies were recovered on the southwest border in the first seven months of this year, a 17-percent increase from the same period in 2016. That rise in the death toll comes despite the dramatic drop-off in US Border Patrol apprehensions, which numbered about 140,000 between Jan. 1 and July 31 — roughly half the number of people caught in the same months last year. All told, the numbers indicate the rate at which migrants die crossing the border has more than doubled, according to Daniel Martínez, an expert on migrant deaths at the University of Arizona. “This is a humanitarian crisis,” he says.

In attempting to explain the soaring death rate, the IOM report noted this year’s heavy rainfall, which caused the waters of the Rio Grande to swell and its current to grow faster. At least 57 people have drowned crossing the river into Texas in the first seven months of 2017, a 54 percent increase compared to last year.

Meanwhile, extreme temperatures mean that more people die crossing the Arizona desert than anywhere else along the border, according to the Missing Migrant Project’s count. So far in 2017, Arizona’s Pima County medical examiner has recorded 96 bodies, even though agents in the Tucson border sector, where Pima County is located, apprehended 56 percent fewer people so far this year as compared to the first seven months of 2016.

The IOM report declined to identify a specific cause of the increase in migrant deaths this year, but it pointed to a historical correlation between stricter border policies and an increase in migrant fatalities. According to Martínez, one of the most important drivers of death rates is US immigration policy, which for decades has focused on securing the border by militarizing popular crossing points. “What’s happening here is that the government is making it more difficult to cross, which means that migrants and smugglers are going to try harder to find ways to cross,” says Néstor Rodríguez, a migration expert at the University of Texas at Austin. “When you try harder, you try more dangerous ways.”

It’s a longstanding problem. Starting in the early 1990s, Border Patrol officers shifted to a border strategy known as “prevention through deterrence,” which included programs like “Operation Gatekeeper,” a massive surge in Border Patrol officers and equipment in San Diego, and “Operation Hold-the-Line” in El Paso, in which the sector’s chief patrol agent flooded a 20-mile stretch of border with agents “within eyesight of each other,” Rodríguez says. Apprehensions fell (in El Paso, they dropped by 70 percent), but migrants simply rerouted through the Arizona desert and across the river in South Texas. “More people were dying out of heat exhaustion,” Rodríguez says. “It changed how people died, and then the numbers grew.”

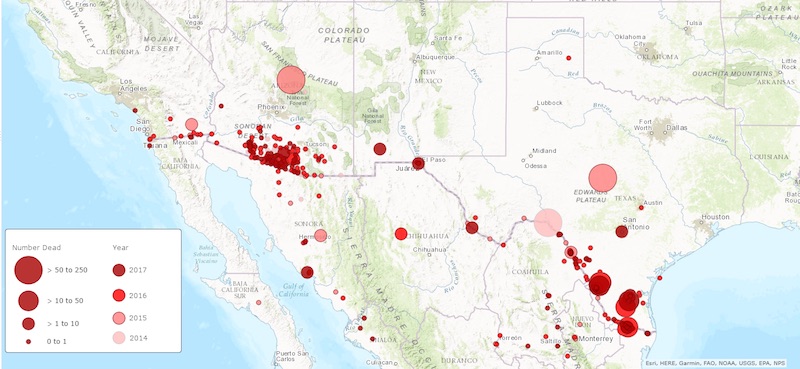

Border Patrol statistics bear this out. Between 1998 and 2010, deaths recorded by the agency in the San Diego sector fell from a few dozen each year to the single digits, while deaths in the Tucson sector shot up from 11 to more than 250. Meanwhile, deaths in the Rio Grande Valley have skyrocketed in the last five years. Here’s where migrant fatalities have occurred on the border since 2014:

Missing Migrants Project

Trump’s plans to ramp up border enforcement — including the hiring of 1,500 more immigration enforcement officers by the end of next year, the implementation of stricter asylum policies, increased detention, and the threat of constructing a border wall — could have a similar effect. While Martínez cautions that there’s not enough data yet to be sure of a trend, he foresees more migrants traveling through dangerous tunnels, by boat or over more extreme terrain to ensure they’re not caught by immigration enforcers. (And that’s not even counting cases like the 10 migrants who died last month after being trapped in an scorching tractor-trailer parked outside a San Antonio Walmart.) “It’s a constant game of act and react,” he says.

Because immigration authorities are increasingly targeting people with strong ties in the United States, many of whom have been here for decades, those people will increasingly risk coming back once deported, Martínez says. “Unless we see a 2,000-mile wall across the border, with moats and whatnot,” he says, “I don’t see this going any differently.”