April is National Poetry Month, and we’re celebrating by featuring examples of “civic” poetry from new and familiar voices. Throughout the month we’ll be discussing what it means to be civic through the art of words. Join us on Twitter at #civicpoetry.

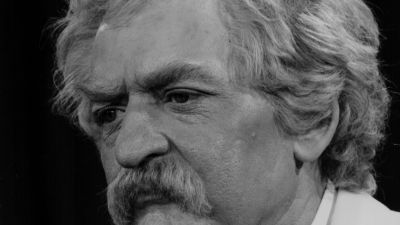

Poet Kyle Dargan talked with Reginald Dwayne Betts as part of our civic poetry month feature.

Kyle Dargan: What do you believe poets and poetry can add to the conversation around public issues, social justice, the environment?

Reginald Dwayne Betts: Poets, under the best circumstances, are hearing things at what Ellison would call “the lower frequencies.” They turn these broad and general conversations into a conversation about the real lives of people, where what is at stake is breathing, is life.

— Reginald Dwayne Betts

KD: What does the word “change” imply for you, and do you have any personal theory of change?

RDB: Change? Albert Murray once said of a character in Train Whistle Guitar that she had forgotten that to live was to suffer. We might add that to live is to also embody the possibility of change. But I have no theory of change, beyond that it happens at every waking moment.

KD: What, if anything, have you been doing or thinking about differently as an artist since the 2016 political cycle?

RDB: Nothing that I could name. My children still need to be loved, my wife. We all need to eat. There is this notion that the sky is falling, and things do often seem erratic (at best). But we’ve been here before. I don’t want to put it like that, but I’m black. In 2010 when I got my college degree, I was the first in the family. Having firsts is a common place thing. So, for me, we’ve always been struggling.

In certain ways, this is a poem about recognition — in terms of what people see in themselves or what others do or do not (or refuse to) see happening to others. Could you talk about the poem as means of compositing necessary imagery? What does the poem present as whole by the end?

Honestly, the poem is me desperately trying to grapple with the multiple ways that men I know, that women I know, get ruined by what living (sometimes) demands. And when I think of compositing — and you say it right here, necessary compositing — the thing is that I’m trying to get at the multiple levels at which we see things.

Every poem I write is not autobiographical, but, in many ways, this one is. There was a crow, and there was this moment when I walked out of a max prison in California and could not escape the pull of death, the drawl of it. The poem’s end — there is just this question of what trauma does to us if we notice it. And if we do, as the speaker here seems to, what does noticing the effect of trauma demand of us.

Triptych

But for is always game.

A man can be murdered

twice, but for science,

his body a pool of blood

in Baltimore & Tulsa,

except, it isn’t, his body actually

slender against the sunlight just

outside a California prison—a crow

rests on a fence near his car.

Visiting hours long done,

(for man not crow,

one of a murderous many

that flies above this barbed wire)

& the cigarette he smokes

is illegal, here, & but for

the magnetic pull tragedy

has on black women he wouldn’t be

here, right now, contemplating

the crimson colored man leaping

into the darkness on his Nikes.

He still says Air Jordans,

because air is important,

adjective swearing to black America’s

aim, if not ability, to soar,

a way to outrun statistics

& the lead in the water.

Alas, metaphysics says

you are only you & no one

else, & a black poet says black

love is not one or one thousand

things, & it all may be true,

but for the fact that the man swears

the crow looks at him dead

as if he is already so,

as if while standing there he

has been murdered

by his brother, murdered

by a cop, & bodied

by a prison sentence as flames

from a Newport’s burning ash,

illuminate his corpse.

“Triptych” was originally published in the Boston Review (January 2017)

This project was co-curated by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and its Puffin Story Innovation Fund.