Ranchers Tucker Dunbar (L), 25, and his father Andy Dunbar feed their cattle on their private land completely surrounded by a federal wildlife refuge near Burns, Oregon on January 6, 2016. They said that they had little time to care for the events unfolding on the fifth day just up the road a few miles at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge Headquarters near Burns, Oregon. (Photo credit: ROB KERR/AFP/Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at Mother Jones.

On January 2, a band of armed militants — led by Cliven Bundy‘s son Ammon — stormed Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, seizing the visitor center both to protest the tangled legal plight of two local ranchers convicted of arson on public land, and to defy the federal government’s oversight of vast landholdings in the West. (You might remember that Cliven launched his own successful revolt against federal authorities in 2014 to avoid paying grazing fees on public land in Nevada.)

For all the slapstick comedy on display at the still-occupied government complex — rival militias arriving to “deescalate” the situation, public pleas for donated supplies including “French Vanilla Creamer” — the armed-and-angry men behind the fiasco are pointing their rifles at a real problem. In short, the ranchers who supply the United States with beef operate under razor-thin, often negative, profit margins.

It’s not hard to see why grazing rights are an issue. Ranchers’ struggle for profitability gives them strong incentive to expand their operations to increase overall volume and gain economies of scale. A 2011 USDA paper found that the average cost per cow for small (20-49 head) operations exceeded $1,600, while for large ranches (500 or more head), the average cost stood at less than $400. Large operations are more efficient at deploying investments in labor and infrastructure (think fencing), the USDA reported.

To scale up, ranchers need access to sufficient land. And in the West, land access often means obtaining grazing rights to public land through the Bureau of Land Management. Hence the bitter dispute playing out in Burns, Oregon: The ranchers accuse the federal government of ruining their businesses through overzealous environmental regulation of that public land.

Now, it’s clear that what the Malheur militiamen appear to be demanding — essentially laissez-faire land management based on private ownership, overseen by local politicians — is a recipe for ecological ruin. In a recent New York Times op-ed, the environmental historian Nancy Langston described what happened last time such a policy regime prevailed in the area: “By the 1930s, after four decades of overgrazing, irrigation withdrawals, grain agriculture, dredging and channelization, followed by several years of drought, Malheur had become a dust bowl.”

But the real beef struggling ranchers should take up with the federal government involves not zealous federal regulation, but rather its opposite: the way the feds have watched idly as giant meat-packing companies came to dominate the US beef production chain. Ranchers run what are known as cow-calf operations — they raise cows up to a certain weight on pasture, sell them to a feedlots to be fattened on corn and soybeans (and other stuff), which then sell them to companies known as beef packers that slaughter and prep the meat for consumers. As the University of Missouri rural sociologist Mary Hendrickson points out, after a decade of mergers and acquisitions, just four companies slaughtered and packed 69 percent of US-grown cows in 1990. By 2011 — after another spasm of mergers —the four-company market share had risen to 82 percent, Hendrickson reports.

Such consolidation at the top of the value chain gives farmers less leverage to get a decent price for their cows. A market dominated by a few buyers is a buyer’s market. The Kansas rancher and rural advocate Mike Callicrate has been making this point tirelessly for years. Callicrate thinks the BLM has been overly burdensome for ranchers in the West, he tells me, but there’s a bigger problem that is “rarely mentioned” either by the gun-toting ranchers or the media covering them: “the historically low, below break-even, market prices for livestock.”

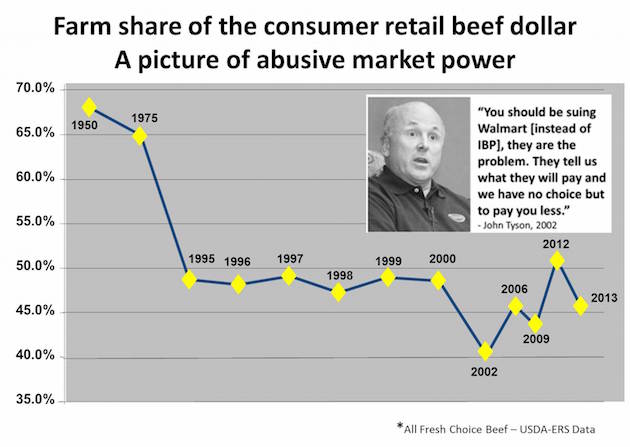

As the big beef packers scaled up and consolidated their market share in the 1980s and ’90s, giant retailers led by Walmart did the same. The result has been steady downward pressure on the beef supply chain: The retail giants pressured the beef packers to deliver lower prices, and the beef packers in turn pressured ranchers. The result has been a big squeeze.

In the chart below that Callicrate created for a 2013 blog post, drawn from USDA data, the trend is clear: Compared to 40 years ago, nearly a third less of every dollar you spend on beef goes into the pocket of the rancher who raised the cow.

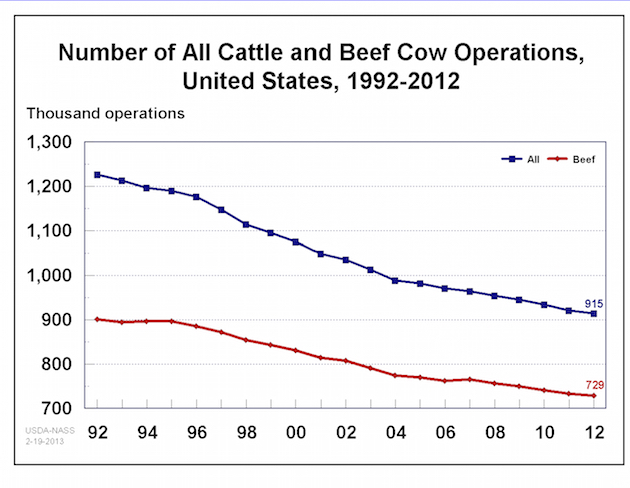

Under pressure from this squeeze, ranchers have had little choice but to scale up, or exit the business altogether—as tens of thousands have done:

Rather than demanding unfettered access to public land, the Malheur rebels could be agitating for federal antitrust authorities to take on the beef giants. As the New America Foundation’s Barry C. Lynn has shown repeatedly, since the age of Reagan, US antitrust regulators have focused almost exclusively on whether large companies use their market power to harm consumers by unfairly raising retail prices. Those regulators have looked the other way when companies deploy their girth to harm their suppliers by squeezing them on price. So antitrust authorities okayed merger after merger, even when deals left just a few giant companies towering over particular markets. As a result, writes Lynn, “In sector after sector, control is now more tightly concentrated than at any time in a century.” The meat industry is a classic example.

During the 2008 election, Barack Obama vowed to challenge the big meat packers and defend independent farmers and ranchers from their heft. As Lina Khan showed in a 2012 Washington Monthly piece, President Obama actually made a valiant effort to do just that — before surrendering to a harsh counterattack from the industry’s friends in Congress.

The current presidential election would be an ideal time for beleaguered ranchers to bring corporate domination of meat markets back into the public conversation. Armed occupations of bird-refuge visitor centers won’t help with that struggle.