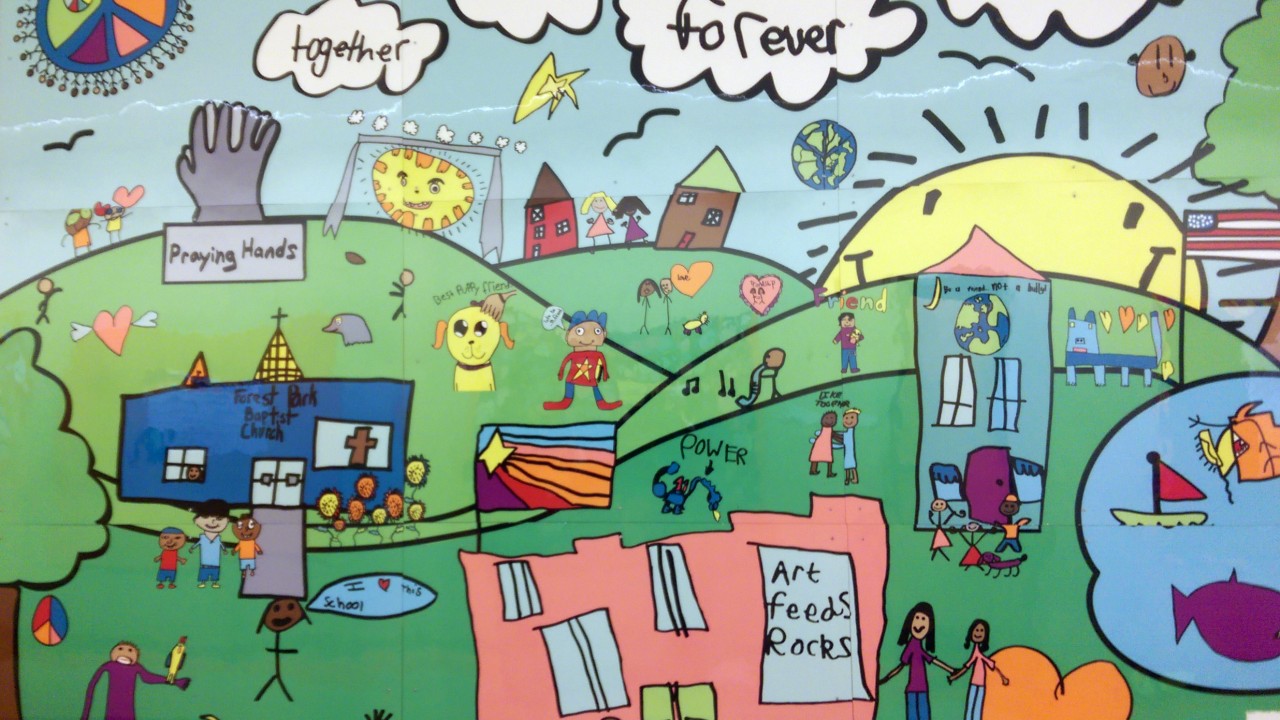

Mural by local artist for Soaring Heights Elementary School that incorporates students’ artwork related to Joplin’s 2011 tornado.

While much attention has been focused this year on the increasing polarization of American politics, there are less visible signs that — at the grassroots level where communities are built — consensus is still possible. Here’s some good news: Last month in Joplin, Missouri, nearly 800 ordinary people gathered to share the extraordinary work that they and thousands of others like them are engaged in. Judging from the 200 or so school districts represented, they are part of a rapidly growing movement that could transform school systems, and the very definition of education, across the South and Midwest, and potentially beyond.

The vision for school-community engagement that began in 2009, just two years before one of the worst tornadoes in US history ripped through Joplin, has blossomed into a growing initiative called, aptly, Bright Futures.

Now established in 38 school districts across seven states, stretching from Oklahoma to Virginia, Bright Futures provides support for districts to put in place its three core components:

- A communication and resource component to meet any child’s basic needs within 24 hours. These needs can run the gamut from backpacks for kids to bring home food over the weekend to steel-toed work boots for a student wanting to enroll in a technical school welding program.

- A leadership and training component to build community leadership capacity to collectively solve the greater challenges facing the community’s youth. These conversations cultivate leadership, creativity and decision-making among stakeholders to develop longterm, sustainable strategies to support youth.

- A service learning component to ensure that students have the opportunity to practice the idea of service before self through hands-on, curriculum-based community service activities.

Bright Futures began small. During his first nine months as superintendent in Joplin, CJ Huff and the team he convened met face-to-face with parents and key community leaders from the social services, business and faith communities. They discussed factors impeding school improvement and how each group could help. As the community worked together, they settled on the three-part reform plan that became Bright Futures: a commitment to rapid response to student needs; cultivating community and school leadership to enable long-term sustainability; and embedding service learning as a part of every child’s school experience.

Two years later, the plan was in place and producing real progress. Then the tornado hit, killing 161 Joplin residents and leveling six schools. But the devastation also brought new opportunities as members of the community worked to rebuild their schools.

When tornado relief began to flow into Joplin, Huff leveraged the opportunity to restructure parts of a system, and redesign schools that had long compounded the disadvantages of vulnerable students. The school district commissioned three Missouri architects to design new schools that conveyed to poor kids – and all of the district’s students – that their voices and their education were its top priorities. They worked with teachers to create spaces that made art and music core components of learning, that encouraged collaboration, and that helped avert discipline problems rather than use force to address them. Instead of inspirational posters that remind students to aim for high test scores, Joplin aimed higher, engraving aspirational messages throughout the schools to share, create, innovate and lead.

The school walls literally speak to kids every day, inspiring them to become not only proficient readers and lovers of math and science, but engaged members of their community and future leaders. And it seems to have had a powerful effect: Joplin’s graduation rate rose from its 2009 rate of 74 percent to 86 percent in 2015 (far higher than the 1996 rate of 54 percent).

The enthusiasm permeating Joplin’s schools and its broader community – from church leaders who discovered newly powerful ways to “do God’s work” to social service providers who found that their efforts were much more effective when aligned with those of schools – quickly spread. When Superintendent Phillip Cook of nearby Carl Junction School District began hearing about members of his community checking Joplin Bright Futures’ Facebook page to see which student needs they could meet, he wanted to harness that energy. Carl Junction became the first Bright Futures affiliate district in 2010, and the first winner, this year, of the newly minted Affiliate of the Year award.

Bright Futures is also reform that teachers believe in: The National Education Association of Missouri gave the program its Horace Mann award in 2012.

President Barack Obama delivers the commencement address at Joplin High School on May 21, 2012 in Joplin, Missouri. (Credit: Mandal Ngan/AFP/GettyImages)

The enthusiasm is perhaps most pronounced among Joplin’s students, who have taken the service learning component of the three-part Bright Futures strategy to heart in inspiring ways. In September 2012, Huff got a call from a student asking him to come to see a presentation she and her 5th grade classmates had put together. When he arrived, he was ushered to a chair and presented with a detailed PowerPoint. When the students heard about the destruction of a Moore, Oklahoma, elementary school by another EF5 tornado, they called the school’s principal to ask what her grieving students needed. They then created a business plan to collect books and donations for library supplies and even a down-to-the-dollar spreadsheet to rent the bus to transport them four hours and back to deliver the books and offer one-on-one support. “I was so blown away,” says Huff, “As superintendent, you don’t often have your students call you at home, let alone pull off something like this.”

At the Bright Futures conference, teachers, ministers, parents, mental health advisors, superintendents, and others from Oklahoma to Virginia described working to counter forces that have “eviscerated” the middle class in their communities. They understand that these same forces make it virtually impossible for teachers to do what they came to schools to do – help kids grow into productive adults and engaged citizens. As Huff, who retired as Joplin’s superintendent last year to help lead and scale up the work full-time, recalls:

When I first became a teacher, I joined my father in pounding my fist on the kitchen table in agreement that parents, not schools, were ultimately responsible for kids’ outcomes, and that we couldn’t ask government or the community to take this on. Then I became a teacher, and I met a bunch of kids who had no parents. I came home every night torn up over the abuse, neglect and trauma these kids were going through, and I couldn’t handle the emotional baggage that went with it. So what do we do? We can pound our fists until we make holes in those tables, but the reality isn’t going to change. And that reality is getting worse every year. We can either build systems that help kids cope and teachers teach, or we can keep losing those kids and all their potential and, as we’re seeing, the teachers, too.

There is no question that we have enormous problems confronting us, and very real reasons to fear the suggested fixes to those problems put forth by some of the candidates vying to be our next president. But we also have real reasons for hope. As Carl Junction Superintendent Cook stated when accepting his district’s award, if thousands of regular people can come together across religious and political lines to do what’s right for kids – by making all kids “our kids” — this really is an America that can be great again.