April is National Poetry Month, and we’re celebrating by featuring examples of “civic” poetry from new and familiar voices. Throughout the month we’ll be discussing what it means to be civic through the art of words. Join us on Twitter at #civicpoetry.

Kyle Dargan: What do you believe poets and poetry can add to the conversation around public issues, social justice, the environment?

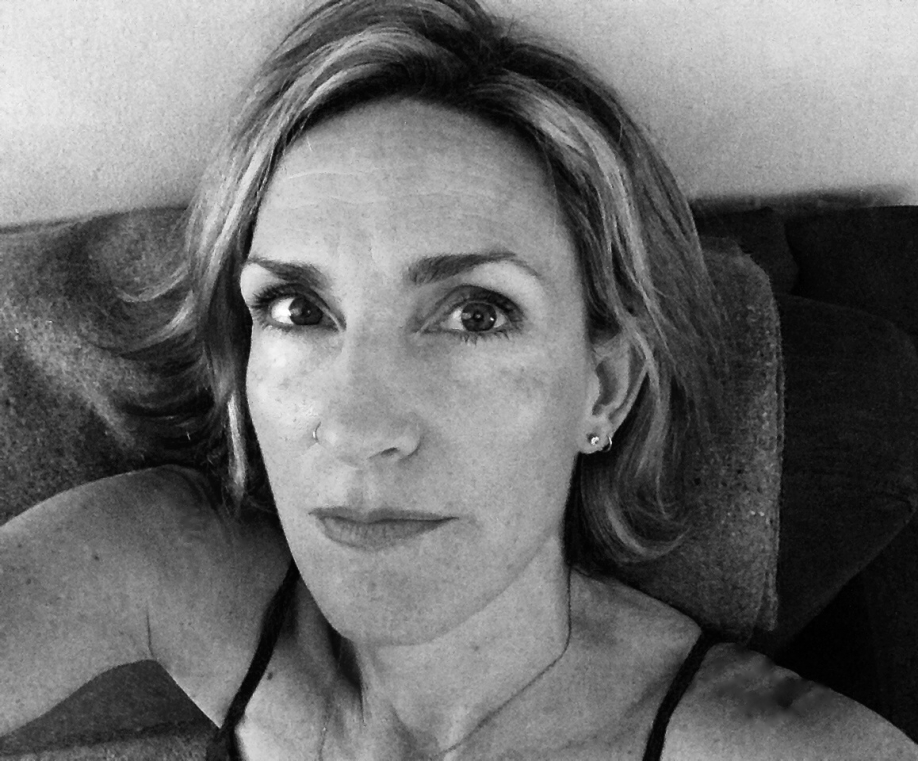

Ailish Hopper: Poetry isn’t just something that happens on the page, or in a performance. Just like young poets sometimes learn from even watching an elder poet step to a mic, or sussing out a problem in their life, all of us can learn from the way poetry calls us to approach things from wholeness. We can not only think and plan for freedom — we can plan from freedom.

— Ailish Hopper

KD: What does the word “change” imply for you, and do you have any personal theory of change?

AH: It’s telling, to me, that we have such an impoverished vocabulary to describe the magic and possibility of what this word points to. “Change,” OK. “Engagement,” OK. “Innovation,” ugh but OK. They are accurate, but mechanical. They are also redolent of the socioeconomic fixedness, and in particular the obsession with “growth,” that unfortunately also permeates much of what is called (or marketing itself as) “change.” The spaciousness of our imaginative labor, the tiger-by-the-tail-ness that marks the artistic process as well as real social shifts, gets boxed and put on the shelf. And even though there’s good thoughts inside (“Anyone can do it!” “We’re in it together!”) the benefit is ultimately going to the bottom line of Status Quo, Inc.

I’m a fan of systems — thinking and seeing, in particular, lately, the work of Adrienne Maree Brown, and this means a slightly different take. Less on discrete tasks and more on interrelatedness. Just as when I revise a poem’s part it can revive the whole, I know that all kinds of social practices might be that critical yeast that, when kneaded into community, will cause us all to Rise. I also really like Adrienne’s urging that we be “an inch wide and a mile deep.” Meaning, less focused on critical mass, scale, grand visions. Or at least, understanding that all of that, and all of that future and past, is right here where we are, pretty much in every social space, neighborhood, workplace, etc., etc. And how are we doing with that?

I don’t like it when people call me an activist, because that word implies what? That everybody else is not active? That may, in fact, be the case. So, all the more reason to not wall off that activity with “_____” and “not ______.” There are people who are incredibly skillful at it, too, though in that case I would call them/their work “organizers.”

— Ailish Hopper

Also, we tend to think of “change” as being “either” for “or” against something (as when people call some of my work “anti-racist”). But I think it’s more about where the work comes from, in ourselves and in our communities. That’s that wholeness, which the mind of poetry requires us to dwell in. I’d like to see a different sense of that word, “activist,” or even “change:” something less about ideas, or separation; more about sensing needs and giving to them, at whatever scale, natural as reaching, half-asleep, for our pillow at night. That’s not an argument for “local” or “small” though that may often be

the setting or type. More like paying more attention to fit: what are our spheres of influence, or skills or temperament. What do we make time for, in our lives? How could community be a natural part of that?

KD: What, if anything, have you been doing or thinking about differently as an artist since the 2016 political cycle?

AH: For me the new presidential administration, as well the concomitant reactions in the States and globally, don’t much change my politics or their expression. And for my art the changes in the American sociopolitical landscape are mostly about audience: how very, very many more people, especially other white people (who are the majority of the decision-makers in mainstream publishing and academia, aka the world of “page poetry”) are waking up to the necessity of involvement. There are poems I wrote last year that now likely mean something quite different to them; to give a concrete example, a poem using the word “revolution” in it (or in a title) might have been suspect, as “too political,” before, but now I’m seeing all kinds of formerly-garden-variety-liberals be genuinely interested in, for instance, neoliberalism, Marxism, etc., etc. People are merrily heading down the garden path of all kinds of previously-too-radical ideas and theories of change.

My art has been in a pretty intense process of becoming for several years now, as a result of writing, then going around reading, poems from my last book, which was about racism in the US, and my place in it as a woman raised to believe I am white (borrowing from James Baldwin’s phrasing). That taught me so much about audience. As in, how many there are, how much learning I had to do to be the same person in each different space — and how much the poetry world reflects the rest of the country’s reinforcement of white supremacy and empire. I think that learning’s drawn me much more into a conversational style; my new work is way more accessible, formally, much more like the riffs I go on in class with students, much more like the intimate heartbreak and inspiration I share with friends or mentors — yet the poems are equally, if not in some ways more, “political” as my last book.

KD: In the poem, your write “We mutually empowered the problem.” This feels like the crux of the poem. How did you decided to implicate the reader in this way throughout the piece, and do you weigh the risks and benefits in doing so?

AH: That poem started out with the phrase “problem.com,” a little joke I had with myself as I watched myself and loved ones gripe about this that and the other thing, which caused me to realize one day that it is, for a lot of us, kind of a hobby. We can actually grow to love our problems, even social or political ones. A whole lot of us prefer the fantasy version—maybe even of justice. And meanwhile, here we are. What shall we do? What shall we do, together. And I also often describe the work I think a lot of us want to do as being willing to be a problem, if a loving problem, for consolidated power, for bigotry, ignorance.

In this poem I meant the “we” as an invitation, not an assumption, but it’s definitely a risk to make even that wobbly claim against the reader. I’m trusting that some readers will actually assume that I don’t mean them, others might see themselves in it, and others I guess will just see it all as thinly disguised me. And all of those are true readings.

What’s interesting to me is the really wide appeal that the poem seems to have had, even given this implication of others. When I perform it I always get questions and comments from people, and when it came out in the poetry journal I got notes from people all over, asking me to explain what the “problem” is, or just saying how much it spoke to them. I wonder a little if the wide range of settings that the poem names, pretty much no one is left out, allows a little more openness to the subtle critique that’s beneath. Or, perhaps it allows us to tap into the longing that the poem is trying to get at also, about what is euphemistically called “politics,” but I prefer Toni Morrison’s phrase: “the romance of community.” Or its power. And this, to me, is where poetry-making and policymaking share a table.

Did It Ever Occur to You That Maybe You’re Falling in Love

We buried the problem.

We planted a tree over the problem.

We regretted our actions toward the problem.

We declined to comment on the problem.

We carved a memorial to the problem, dedicated it. Forgot our handkerchief.

We removed all “unnatural” ingredients, handcrafted a locally-grown tincture for the problem. But nobody bought it.

We freshly-laundered, bleached, deodorized the problem.

We built a wall around the problem, tagged it with pictures of children, birds in trees.

We renamed the problem, and denounced those who used the old name.

We wrote a law for the problem, but it died in committee.

We drove the problem out with loud noises from homemade instruments.

We marched, leafleted, sang hymns, linked arms with the problem, got dragged to jail, got spat on by the problem and let out.

We elected an official who Finally Gets the problem.

We raised an army to corral and question the problem. They went door to door but could never ID.

We made www.problem.com so You Can Find Out About the problem, and www.problem.org so You Can Help.

We created 1-800-Problem, so you could Report On the problem, and 1-900-Problem so you could Be the Only Daddy That Really Turns That problem On.

We drove the wheels offa that problem.

We rocked the shit out of that problem.

We amplified the problem, turned it on up, and blew it out.

We drank to forget the problem.

We inhaled the problem, exhaled the problem, crushed its ember under our shoe.

We put a title on the problem, took out all the articles, conjunctions, and verbs. Called it “Exprmntl Prblm.”

We shot the problem, and put it out of its misery.

We swallowed daily pills for the problem, followed a problem fast, drank problem tea.

We read daily problem horoscopes. Had our problem palms read by a seer.

We prayed.

Burned problem incense.

Formed a problem task force. Got a problem degree. Got on the problem tenure track. Got a problem retirement plan.

We gutted and renovated the problem. We joined the Neighborhood Problem Development Corp.

We listened and communicated with the problem, only to find out that it had gone for the day.

We mutually empowered the problem.

We kissed and stroked the problem, we fucked the problem all night. Woke up to an empty bed.

We watched carefully for the problem, but our flashlight died.

We had dreams of the problem. In which we could no longer recognize ourselves.

We reformed. We transformed. Turned over a new leaf. Turned a corner, found ourselves near a scent that somehow reminded us of the problem,

In ways we could never

Put into words. That

Little I-can’t-explain-it

That makes it hard to think. That

Rings like a siren inside.

“Did It Ever Occur to You That Maybe You’re Falling in Love” originally published in Poetry (January 2016)