Poet and former publishing executive James Autry joins Bill to talk about issues of art and of heart. He shares his poems with Bill and discusses his and his wife Sally’s challenging but inspiring experience raising their autistic child.

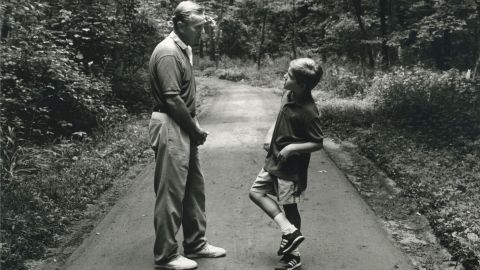

From politics to poetry. Jim Autry and I go back awhile. Maybe you remember the two of us, long ago, sitting under a tree at a cemetery in the Deep South.

BILL MOYERS on Power of the Word: Read this for me.

JAMES AUTRY on Power of the Word: Genealogy. You are in these hills, who you were and who you will become, and not just who you are. She was a McKinstry and his mother was a Smith. And the listeners nod at what the combination will produce. Those generations to come of thievery or honesty…

BILL MOYERS: There we were, awash in memory, in a graveyard crowded with kinfolk from his boyhood in the Mississippi Delta. Jim had written his first collection of poetry. "Night’s Under a Tin Roof" he called it. The book is still a favorite of mine, filled with recollections of a life and people now long gone. Of family reunions, church revivals, and country funerals.

He moved on and up in the world: becoming president of the magazine group of the Meredith Corporation, the Fortune 500 media giant based in Des Moines, Iowa. That’s where he met and married Sally Pederson and where they raised a son, Ronald. Because of him, both Jim and Sally became advocates for children and adults struggling with autism.

In time, Sally would be twice elected Iowa’s Lieutenant Governor. And Jim, after retiring from the publishing trade, became a sought-after adviser to business organizations. He keeps writing books of poems, practical philosophy, and remembrance, including “Love and Profit: The Art of Caring Leadership,” “The Servant Leader” and Looking Around for God.” This is his latest, “Choosing Gratitude: Learning to Love the Life You Have."

Jim, welcome to the show.

JAMES AUTRY: Good to be here, Bill.

BILL MOYERS: When you were at Meredith Corporation, Fortune 500 company you were widely admired as a caring executive. We don't read much about that kind of CEO anymore. And I'm wondering if you have stayed enough in touch with the world of business to offer an opinion on what's gone wrong.

JAMES AUTRY: You know, there are a lot of sort of clichés and there are a lot of, you know what I call them, ideas du jour that go into business. And certainly a more humanistic way of managing sort of swept through the business world. Until, until the financial people took over as CEOs. You know in the old days, people who made the product became CEOs and became, the people who sell the product became CEO. And now it's the people who keep the numbers who are made the CEOs. And it also is driven very much by this incessant pressure for earnings. So I think that that’s been, that’s had a negative impact on organizations. The one I used to work for is much less people-oriented than it used to be. Good people there, they're just a different culture. I do think that there are still organizations, still companies, I get called to speak to them, who try their best to do what I call servant leadership. That is they are servants to their employees. They realize that giving the employees the tools and support they need to do the job will allow them to do a good job and thus produce for the company. They realize that if you have a company that's trying to serve people somehow, whether you're carrying them on an airline or serving them coffee, that you can't do that unless the people are committed to what they're doing. And they won't be committed to what they're doing unless they're valued for what they're doing. And they can't be valued unless you nurture them and support them and give them the tools and encouragement they need.

BILL MOYERS: I want to make it clear that, servant leadership, nurturing your employees, doesn't mean tolerating incompetence.

JAMES AUTRY: Absolutely not. I mean, when I speak I say, "Listen, this is not the soft stuff. If you think this is soft, you should try it a while." This is the hard stuff. You have to extend yourself. You have to be there. You have to get out of your office and get away from your club and your trips and actually be there and focus on the well-being of the employees. That's hard work. It's very hard work to fire someone. Even to discipline someone. But you have to do that with generosity and a spirit of caring and you have to know, "This person I'm about to fire is never going thank me for this." But it's something that all the other people probably will, because that person's work has made a negative impact on everybody else. It's hard work. And the easy way to do it is to be one of these tough guy, kick them in the rear. You know, it's much easier to slam your fist down and yell than it is to say, "Bill, you know, we really need to talk about your performance."

BILL MOYERS: You've made those decisions. And of course this came from it.

JAMES AUTRY: Yes. "On Firing a Salesman."

It is like a little murder, taking his life, his reason for getting on the train, his lunches at fancy restaurants, and his meetings in warm and sunny places where they all gather, these smiling men, in sherbet slacks and blue blazers, and talk about business but never about prices, never breaking that law about the prices they charge.

But what about the prices they pay? What about gray evenings in the bar car and smoke filled clothes and hair and children already asleep and wives who say, 'you stink,' when they come to bed? What about the promotions they don't get, the good accounts they lose to some kid MBA because somebody thinks their energy is gone?

What about those times they see in the mirror or the corner of their eye some guy at the club shake his head when they walk through the locker room the way they shook their heads years ago at an old duffer whose handicap had grown along with his age?

And what about this morning, the summons, the closed door, somebody shaved and barbered and shined fifteen years their junior trying to put on a sad face and saying he understands?

A murder with no funeral, nothing but those quick steps outside the door, those set jaws, those confident smiles, that young disregard for even the thought of a salesman's mortality.

That's the first business poem I ever read in public to a gathering of businesspeople. It was a conference I was going to speak. I thought, "I'll just read that poem." It was the first business poem I wrote. And I looked out there and there were guys, mostly men, grey haired. And their eyes were watering. And I thought, "They've done this. Maybe this is what I'm supposed to do

BILL MOYERS: When did you write your first poem?

JAMES AUTRY: When I started writing poetry my mother had just died. And then later my brother was diagnosed with cancer. My father died. My brother died. I'd gone through a divorce, which is its own little death. And it, it was weighing heavily on me. So it found its way into my poetry. And coming to grips with it and dealing with it and being grateful for having been brought through it is also in my poetry.

BILL MOYERS: This one comes to mind as you talk.

JAMES AUTRY: “Disconnected."

BILL MOYERS: "Disconnected."

JAMES AUTRY: Ten years after the death of my brother. This actually happened to me.

How could I have explained to the woman who answered that I'd dialed not to reach her but just to dial that very number as I have so many times before to hear it ring once again and remember for a moment a voice I'll never hear again?

Have you have on your telephone any telephone numbers of people who've died? I do. And I just can't erase them. Can't.

BILL MOYERS: Well, my mother's been gone 12 years and rather occasionally I will find myself about to reach for the phone thinking that I would call her. Then suddenly realizing, she's not there to answer. And the intervals have become longer, but I still have that impulse from time-to-time.

JAMES AUTRY: Yeah. I know exactly what you mean. The whole idea of a presence with an absence. That we carry those people with us. You know, they live on through us. My brother, for instance, was a great card. And he'd, when we'd start to drive onto a highway where there's a yield sign, he'd just suddenly in an English accent say, "Yield. I shall never yield." So he's with me every time I see a yield sign. So that's the presence within the absence that I try to capture in some of my poetry.

BILL MOYERS: I've long been envious, of your capacity for detail, for example, your poem "Reminisce at…"

JAMES AUTRY: Toul. It's a little town in France.

BILL MOYERS: And you were there?

JAMES AUTRY: I was there when I was in the Air Force. I was stationed very close to there. Now I was flying jet fighters, we had a nuclear mission. We didn't fly with nukes but we stood alert with them. And so it was a dicey time.

"Reminiscence at Toul."

Thirty years ago on New Year's Eve drunk on French champagne we shot bottle rockets from the windows of Hank and Willi’s rented chateau overlooking Nancy.

It sounds so worldly which is how we wanted to think of ourselves, but Lord, we were just children, sent by the government to fly airplanes and to save western Europe from World War III.

We thought we had all the important things still left to do and were just playing at importance for the time being. It never occurred to us, living in our community of friends, having first babies, seeing husbands die, helping young widows pack to go home, that we had already started the important things. What could we have been thinking, or perhaps it's how could we have known that times get no better, that important things come without background music, that life is largely a matter of paying attention.

BILL MOYERS: "Life comes without background music."

JAMES AUTRY: Which we raised on movies tend to think that when good things happen and things are good, there's great background music.

BILL MOYERS: Choosing Gratitude. Why gratitude and why now?

JAMES AUTRY: Well, I guess it started with my increasing frustration about how polarized we are in the country. How much discontent there is. People ask me now, "How are you doing?" and I say, "Considering everything there is to complain about, I have no complaints." So it was partly that and partly my own need to bring some sort of calmness in my life. I think I've told a story in the book of how I would walk in the morning. I'd come back and be all agitated about the war or the politics. And I thought, "You know, this isn't supposed to be healthy I don't think." So it evolved into a gratitude walk and where I try to just make it like a meditation. Every step I try to just think of something I'm grateful for.

BILL MOYERS: But how do you find and choose gratitude when, as you say, you read the news, you watch television, you go online and get the latest from the world.

JAMES AUTRY: Well, the world is very much with us. And I'm no Pollyanna but I choose gratitude as an interior journey. An interior practice, sort of a discipline. That if I can choose to be grateful for my life, love the life I have in the midst of all this, then I can be grateful for other things. I think if one practices gratitude as a way of being you become a more generous, supportive, loving person.

BILL MOYERS: You wrote a poem in 1984 called "New Birth for Sally."

JAMES AUTRY: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: Would you read that?

JAMES AUTRY: Sure. "New Birth for Sally, Spring 1984."

From her sure knowledge that everything would come out all right, things began to come out all right, out through the present day horrors, through my fears and loss and grief, through the demons lurking around everything I do. As if directly from that optimism, Ronald came unconcerned into the cold and light, no longer surrounded by the sounds of Sally's life, but sliding easily into the doctor's bloody hands then snuggling back onto his mother's warmth, none of his father's wailing against the world, none of that waiting for the next shoe to fall. And I count toes and fingers and check his little penis and touch the soft spot on his head and watch the doctor probe and squeeze, not believing that everything came out all right.

Later I wonder how these years have come from pain to death to pain to life to what next? A baby babbling in the backpack, a mother walking her healthy pace, a dog trailing behind, and me holding on, through the neighborhood, through everything, with each day one by one coming out all right.

BILL MOYERS: Now that was written when?

JAMES AUTRY: 1984. That's right.

BILL MOYERS: You didn't know about the autism then?

JAMES AUTRY: We didn't. He was only about seven months old then.

BILL MOYERS: So you were writing in celebration of this life and all it had to promise?

JAMES AUTRY: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: When did you discover that he?

JAMES AUTRY: He, was about two and a half. I mean his developmental milestones weren't met throughout. And then finally when he was about two and a half years old we were told that something was wrong and we began to go through the diagnostic process.

BILL MOYERS: Did you have a hard time with it?

JAMES AUTRY: I had a hard time at the beginning and not for the reasons of, you know, being a macho father and my son is… none of that stuff. It's just that I knew he was going to have a tough time in life. And I didn't quite know how to deal with it. Sally, on the other hand, immediately started learning about autism. Getting active and doing all those things. And became an inspiration to me to get involved.

BILL MOYERS: It wasn't ever easy, was it?

JAMES AUTRY: Never easy. Parenting is not easy to begin with but parenting a child with a disability, and particularly with an intellectual disability like autism, which the behaviors can just fly off and all of a sudden. It's difficult.

BILL MOYERS: And then there was the day when he was six years old and he came down the stairs?

JAMES AUTRY: Yeah. Jumping down the stairs, one at a time, saying, "Happy boy. Happy boy. Happy boy."

BILL MOYERS: And what did you think about that?

JAMES AUTRY: I mean every little thing you have to celebrate. The first thing you have to do is you have to stop mourning the child who's never going to be and start celebrating the child who he is. Sally was better at that than I was.

BILL MOYERS: That's my favorite poem in the book. You call it "Patience." Set that one for us.

JAMES AUTRY: Well, we take Ronald to a horse ranch in Colorado. We did it for 13 years, because horseback therapy was good for him. He related to horses and it was just great for his development. So this takes place at that dude ranch. It's titled "Patience."

The porch was alive with hummingbirds, Swarming the theatres, Hovering with their invisible wings, Darting away and back, Delighting all of us dude ranchers Sitting in the big Adirondack chairs After a day on the trail. Ignoring the admonitions, Ronald could not stay away. 'Don't worry,' the ranch boss says, 'He can't catch them.' But the boss did not count on a patience He'd never witnessed before: A boy, moving as slowly as the wings were fast, The birds waiting to be cupped in the boy's hands, Then released back to their busy work, Each christened with a new name.

BILL MOYERS: That struck me because Ronald actually catches one.

JAMES AUTRY: He caught a dozen of them.

BILL MOYERS: How did he do it?

JAMES AUTRY: Just reaching slowly up to where they were on the feeders, holding out his hands. And then as they sort of settled in, he'd bring them down. He'd always name them like, "Good-bye Steven," and release them. And he did that with butterflies and well. You and I catch butterflies like this.

BILL MOYERS: Oh yeah.

BILL MOYERS: One hand. You know?

JAMES AUTRY: He just reaches out slowly and it's as if they're waiting for him.

BILL MOYERS: There's a gentleness in how you describe it.

JAMES AUTRY: Ronald is a very upbeat, loving person. When he was about seven or eight years old we saw a blind man. And a few minutes later Ronald says, "Dad, could they take one of my eyes and give it to him and then we'd both be able to see?" That's the goodness within Ronald. And it helps me. It helps me try to find more goodness in myself. He's a loving, upbeat, happy young man. And he played in the band. Played cymbals. And in the middle school band and the high school band. He ran track in high school. Now, you know, he wasn't fast. But the people were so abiding and supportive. I mean the coach let him run on a relay, knowing there was no way the relay team was going to win because he couldn't carry his part of it. But whenever he ran and he came around the track, the teammates would run with him the last stretch. And say, "Go Ronald." And the people in the stands would applaud. I mean it was in a way, Ronald gave people the opportunity to sort of find the divine in themselves. To find the best in themselves.

BILL MOYERS: He's how old now?

JAMES AUTRY: Twenty, he's going to be 29.

JAMES AUTRY: He's lived in his own apartment for six years. He has had a job for three years. Lives alone. He's only 15 minutes from our house. He has a dog. He has a cat. He drives. He has a car. He gets up every morning at 6:00, calls me and gets the weather. Feeds his dog. Takes his dog out, as he says, "To do her stuff." And then he gets dressed and he catches the 7:00 bus to work. And he works half days, five days a week.

BILL MOYERS: What do you take away from those experiences?

JAMES AUTRY: I take away a feeling of blessing. Of thankfulness. But it all comes into gratitude to me. It’s just, I'm so grateful for my life as it is and realizing I didn't used to be this way. Listen, this isn't St. James the Perfect.

BILL MOYERS: I've never known that James.

JAMES AUTRY: But you know, I was a well-known grouch. And it's been an awakening for me through all these experiences.

BILL MOYERS: There is a poem in particular that seems to me to get at what you are saying it’s, you call it "A Sentimental Poem." Read it for us.

JAMES AUTRY: Well, this is for my wife, Sally, on our 20th wedding anniversary. And we've been through quite a lot of things together. So I wrote this to her. And it's called "A Sentimental Poem." I say,

For Sally on our 20th wedding anniversary I know that contemporary poets, if they are to escape the wrath of critics, must avoid the curse of sentimentality, But here I am, 20 years married today, with nothing to write about love that is not sentimental; a tumor, a surgery, a scribbled prayer and the one hundred and thirty-ningth psalm; the diagnosis of something wrong, something wrong with our child; hours and days and years of working to help him find himself in this world; deaths of a father, a brother, a beloved sister, more surgeries and recoveries, a son in a struggle with addiction. And I haven't even gotten to the joys, not talked about the celebrations of life, the friendships, the gatherings of family, and the great and enduring spiritual quest. If I am doomed to write of sentiment, then let it be said that I also write of blessing, all of it, the pain, fear, anguish, laughter, whimsy, joy, blessings all, because you arrived in my life with an expectation of blessing, a sure belief that there is nothing but abundance and our job is to face it all with gratitude.

BILL MOYERS: "A sure belief that there's nothing but abundance."

JIM AUTRY: Well, you know, Brueggemann writes about the theology of scarcity. The theology of abundance. And we talk about scarcity and abundance. And our society, I think we live with a fear of psychology of scarcity. That we don't have enough. We just don't have enough. And there is another psychology of abundance and it is that everything, even the negative stuff, is, contributes to the abundance of life experience. I mean, those negative things, you know, that child with that disability, all of that was terribly painful. I wouldn't take any of it back. You know? I wouldn't take any of it back.

BILL MOYERS: The book is "Choosing Gratitude: Learning To Love The Life You Have." Jim Autry, thank you for being here.

JAMES AUTRY: Thank you, Bill.

James Autry: Two Poems

James Autry: Two Poems