In the course of his long career as a journalist, William L. Shirer was an eyewitness to the history of our times. His best-selling books, among them Berlin Diary, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, and a trilogy of memoirs, have given readers a front-seat view of major events. In part two of Bill Moyers’ discussion with Shirer, the famed journalist discusses the evil of Nazi Germany and his post-WWII life. (Read part one of Bill’s conversation with William L. Shirer.)

TRANSCRIPT

BILL MOYERS: [voice-over] For most of his adult life, William L. Shirer has been an eyewitness to history. Fresh out of college, he arrived in Paris in 1925 to become a newspaper reporter. During the ’20s and ’30s, he covered stories throughout Europe and spent two years in India, reporting on Mahatma Gandhi. In 1937, Shirer was hired by Edward R. Murrow to open the European bureau of CBS News. As a pioneer in broadcast journalism, he was in Rome for the death of a pope, in Berlin for the rise of Hitler, on the front lines for the fall of France. When Nazi censorship made honest reporting impossible, Shirer returned to the United States, broadcasting a weekly news analysis on CBS and publishing his first best-seller, Berlin Diary.

His career in broadcasting ended in 1947, when CBS canceled his program. But Shirer created a new career as an author, drawing on his years in Nazi Germany. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich became one of the biggest sellers in publishing history. He has since written about his years with Gandhi and has published a trilogy of his memoirs, Twentieth Century Journey, The Nightmare Years and A Native’s Return.

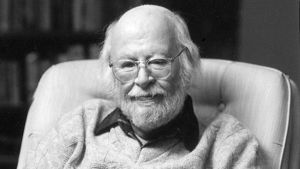

Now at age 86, William L. Shirer is at work on yet another book, this one about the final years in the life of Tolstoy. We talked at his home in Lenox, Massachusetts.

[interviewing] You came face to face with many of Hitler’s top men, the men who were responsible for carrying out the evil he ordered. And yet you described them in your books as dimwitted, somewhat stupid, dull, tedious. And yet these were men who were about to take over the world.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: It’s amazing what men they were, or how they could take over a great country. I think part of those adjectives were about Rebentraub. And I remember my editor of the book said, you know, “Don’t you want to come down a little bit about those adjectives?” Rebentraub, who was the foreign minister, was one of the most stupid men who ever lived, and Himmler thought he was another Bismarck, you know.BILL MOYERS: You said most of the misfits around Hitler were so outlandish that it was almost impossible to believe they were playing key roles in running this great and powerful country.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Yeah. Himmler, who developed up the SS, he always looked to me like a chicken farmer, but behind those glasses of his and his mild manner was a terrible killer. Goebbels was a cynical guy. He was clever about the-intelligent about the Germans, but he knew his own poeple, but he was abysmally ignorant of the world beyond the German borders. He had no conception of British character. The British have a bulldog character, which I much admire. The French he didn’t understand. The Russians were beyond him. The Americans he thought were a bunch of people run by Jews and blacks, as he often put it.

They were a group of people, I’m talking about when they came up to power, Goering, a swashbuckling guy, you know, ignorant, who couldn’t have made it in any other country but in the Nazi party.

BILL MOYERS: Misfits.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Absolute misfits in society. So many of them had, you know, many of them had criminal records. But they were misfits, that’s the word.

BILL MOYERS: When you looked at these men, were you aware that they were capable of such evil?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: To be honest, I don’t think I was, in ’34. I certainly didn’t think there would be genocide, and what happened after the war started. You had a bit of a taste of it the weekend that they eliminated the SR, the leadership of the SR, during which they also shot a few personal enemies of Hitler and Goering and Goebbels, including a general, the head of the Catholic social movement, a wonderful guy. The coldbloodedness. We don’t know exactly how many they killed, but they killed at least 700 or 800 in cold blood.

BILL MOYERS: But here, to me, is the key question. Do you think they thought that what they were doing was evil, or does the totalitarian mind obliterate the distinction between good and evil, right and wrong?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Obliterates it, certainly. There’s nothing at all in the documents which I read which include Hitler’s long talks to his cronies, there’s nothing in what they said to indicate that they considered what they were doing as evil. I mean, throwing these people into the gas chambers and so forth. We did not predict that. And I knew nothing about that for a time because I left Germany at the end of 1940. The Potsdam conference, I think, was a month or so after that, in January, in which the “final solution” was adopted.

BILL MOYERS: The program to exterminate the Jews?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Yeah. Terrible term in itself, the final solution. Awful. Makes my stomach off.

BILL MOYERS: When you first heard about it, when you first were told that a whole people were being systematically obliterated, did you believe it?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: I couldn’t believe it, no. And that information came very slowly. And I certainly missed the story myself. But I remember first hearing it in London in ’43.

BILL MOYERS: That late?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: That late, two years after it really started, or at least a good year. And I heard it from people in the British Foreign Office, and I remember one weekend I spent down with Eden, whom I’d known as a kid, practically, when he used to come to Geneva.

BILL MOYERS: Anthony Eden?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Anthony Eden, he was then foreign secretary. And I asked him about it, and he was somewhat, I think it’s fair to say, somewhat anti-Semitic. But anyway, he said it was-there was no truth in it, they were getting these reports, there was no truth in them. I checked when I came back into America, I think with Harry Hopkins, and he told me that Roosevelt had heard these things but Roosevelt, President Roosevelt, did not believe them.

During all that time, the Jews were trying to get the word out, and I believe they did. We know now that they did, and it’s a very bad record that. the British Foreign Office and the American State Department, lin which there were also some anti-Semites, I think they have a very bad record. I have a bad record, too. I did not get the story, really, until Nuremburg.

BILL MOYERS: After the war you sat there listening to this testimony, looking at these pictures.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: I sat there. One day when they had these terrible pictures, and when we’d had the testimony of a guy named Hoess who’d been the commander at Auschwitz, he was almost proud of it. I went home that night and I couldn’t eat dinner. I think that would be true of my colleagues, too. And for-I was in a daze for three or four days, I think. 1-one’s imagination could not grasp it. They suddenly threw it at us. But we should have learned about it in ’44, and I didn’t, and the government didn’t put it out.

BILL MOYERS: Somehow, there is, seems to me, a reluctance on the part of an optimistic people like Americans are to acknowledge the real presence of evil.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: I think so. There’s a wonderful quote, I can’t do it exactly, from [unintelligible], Reinhold Niebuhr. He said, “A people without a sense of tragedy have difficulty admitting the evils of the day.” I think that’s true.

BILL MOYERS: You said that not only the men immediately around Hitler, but so many of the German people easily believed everything he said, even the most foolish nonsense.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Well, you know, we are still-I suppose most of us correspondents covered dozens if not hundreds of Hitler’s speeches. We often sat pretty near the front, and as he was-he always started his speeches in the same way, “Fourteen years ago,” so under our breaths we’d repeat the words. But then later on, when we get into some of the terrible lies, it’d take your breath away. [Unintelligible] working on the German people, mouths open, their eyes popping out, the gospel truths. He had that wonderful sense of contact with his own people, communication with his own people.

I remember once at a Nuremburg party rally, in one of those wonderful churches in old Nuremburg, probably seated 2,000 people, he gave a talk on art. Art. Well, I can’t imagine President Reagan or even President Bush or even your President Johnson giving a lecture on art. Oh, it was terrible, what he said, but what fascinated me was he looked around and that audience was spellbound. For two hours, the most idiotic things about art-I’m not an artist, but I think I have a tiny appreciation for it, it was just awful, the distortions of it.

BILL MOYERS” Someone wrote that Hitler’s strength was in the fact that he was incorrectly diagnosed by astute simpletons who forgot that history belonged to the realist. He was a realist in one sense, wasn’t he? He knew that power-

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: He was, but he was also ignorant of history, I think. And he was terribly ignorant, like Goebbels, perhaps even more so -Goebbels after all was a Ph.D., whatever that may mean -but at least he’d been educated in a German university. But Hitler had a great self-education. In his youth he had read a great deal. And he, too, had no idea, particularly of the English. As a matter of fact, it was his miscalculation of the English that plunged them into war. I mean, the main thing was Stalin and his pact with them which released them in the east. But he misjudged the British, and he completely misjudged us.

BILL MOYERS: But he didn’t misjudge the French, because he knew when he went in in ’38 into the Rhineland, or was it ’36

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Thirty-six.

BILL MOYERS: -’36, that France was not going to retaliate, although the records now show that if the French had stood up to Hitler when his armies marched across into the Rhineland, he would have collapsed, the armies would have retreated.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: They could have crushed him in a moment, I think. They had a great army. The Germans had very little by that time, and the German military people knew that they couldn’t take on the French. It was a bluff on Hitler’s part that he got by with. He knew the French better than almost anybody.

BILL MOYERS: You’re writing a book now about Tolstoy, and it reminds me that Tolstoy had this notion of the law of predetermination. His thesis was that so many factors go into any event that one can only conclude it had to be inevitable. You believe that? Was Hitler inevitable?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: No. Hitler was not inevitable. If the Germans had worked the Weimar Republic honestly, we never would have had a Hitler.

BILL MOYERS: What do you mean, if they had worked it honestly?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Well, if they’d worked democracy. Do you realize that the constitution of the Weimar Republic was probably the most liberal in the world? And I must say, when I first went up to Germany, I was a youngster working in Paris, and I used to get an assignment up there occasionally. 1-and I sort of grew up in the Sorbonne quarter, I had a lot of student friends and young teachers at the Sorbonne, the university. But I went up to Germany, I found I was more akin as a young American not long out of college with the Germans under Weimar. They were interested in the arts, they were interested in peace, they were interested in social matters. A lot of them were socialists, some were Communists, some were middle-of-the-road and so on.

BILL MOYERS: Idealists, all of them?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Very idealistic. But in the end they didn’t work it. And one of the most disillusioning experiences of my life was when I went back to work in Germany, say, only seven or eight years later, and looked up some of those people. Most of them were high-bigwigs in the Nazi party, or in the German Foreign Office, where you had to be-by that time, you had to be a Nazi, and so forth. It was-it made you think.

BILL MOYERS: What did you think?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Well, I thought, “How the deuce could it have happened?” And I did see a few of these people, and I was full of myself at that time, I guess, and I would say, “How in the deuce can you-I mean, you know, we’re old acquaintances, at least, how can you believe in all this nonsense, you know?” Well, I’m naive, but I’m not that naive, and I could go on with-they said: “Listen, we have a career to make, just like you have in America. And these people are the future, they’ve taken over the country.” But worse than that, they began to believe in it, and that was the worst thing.

BILL MOYERS: One of these days, the last living witness to what happened in Germany, what happened in this century, will be dead. What do we do about the memory? Do you think enough people will read books like these?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: I don’t think so. I think-of course, now a lot of them did read it, you know, when the Third Reich book came out, the publishers said nobody will read it, and for some reason that they don’t know, a lot of people read it.

BILL MOYERS: I recall that when you were dismissed from CBS in 1947 -fired, to be blunt about it -AJ. Liebling wrote, “If Shirer will work at it carefully, if he will plan this book,” that you were writing about Nazi Germany, “if he will go over every paragraph twice,” he said, “then all of us may be in debt to the man who fired him.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Yeah?

BILL MOYERS: Well, we are.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Well, thank you for saying so.

BILL MOYERS: You wouldn’t have written these books if you’d stayed on the air, probably.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Oh, it was a lucky break, you know. I felt very sorry for myself, as one does when you’re fired and you have a family to support. The greatest thing that ever happened to me. A reporter-well, you know, you’ve been in the business, all reporters want to write books, they want to write novels, and they keep putting it off because the easy money’s coming in. And the only reason that I did it was not because I had a lot of courage, because I was thrown out, I had nothing else to do.

BILL MOYERS: Luck has played -good luck and bad luck -have played significant roles in your life, have they not?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Oh, I’m a great believer in luck. And we all have our portion of bad and the good, and we sort of resent the bad, but it’s a necessary part of life on this Earth. I had a reporter from the Times up here the other day who complained about that theory. I told him I’ve had a lot of luck in my life, luck to be sent to India when Gandhi was there, luck in a sense to have covered Nazi Germany. It was luck. And many stories that I had, they were luck. I was coming back through Mesopotamia once and I saw a little sign, Ur Junction, where the train would stop. And my Presbyterian background came up, and I thought, Ur Junction, that must be a terrible British way of saying Ur of the Chaldes, Ur of Abraham. So I toss out my bedding and so forth, and went to a little rest house. And there was a Turkish guy, spoke a little German, and he said, “I know why you’ve come, great excitement in the Teg over there. And we looked through the window and about five miles over the desert there was obviously an excavation. So after breakfast, he got me a mule and we drove over to the place. And I stumbled upon Leonard Woolsey, who had just discovered two great things: the physical evidence of the biblical flood, which many scholars had thought was a myth; and second, even more important, probably, he discovered a new civilization nobody had heard of before, that of Sumer-

BILL MOYERS: Sumer.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: -Sumerian civilization. Well

BILL MOYERS: There you were, just at that moment.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: -it was luck. It was luck.

BILL MOYERS: Curiosity plays a very big role. A lot of people were on that train who didn’t get off.

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: That’s right, yeah. Yes. Well, I’m crazy that way.

BILL MOYERS: You said you learned a lot from the people you read and have been around. What did you learn from Gandhi and what prompted you to write this memoir about him, because you said that your admiration of Gandhi bordered on adoration?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: It did indeed. I thought then and I still think so he probably was the greatest man of our time. He was a great political leader and he was a great spiritual leader. And with all the baggage that I came out there, of western civilization, what little I had acquired. He showed me there was another world, completely different world, a world where force didn’t always prevail, where nonviolence, if properly directed, could overcome bayonets and that sort of thing. And maybe, above all, he talked a great deal about love, spiritual love. And as a matter of fact, he used to lecture me by saying, “Love is God.” He would say, “That’s the only God that I really recognize, is love equates God.”

Well, that was difficult for me to get. So I got from him-I got a different kind of religion. I never could go back, after two years in India, to my Presbyterian church as a member, as a worshiper. He taught me something that’s been wonderful in my life, what he called comparative religion. He said-he was a devout Hindu, but the Hindu religion is very tolerant, you know, much more tolerant than any of our religions or Islam. And he said, “I take the best of all religions.” And we would talk, and he said, ”Well, I find you terribly ignorant. You’ve never read the Koran, you’ve never read the Baghavad Gita, you’ve never read the Vedas.” And he prescribed me some reading, and I spent quite a bit of time in those two years reading, the Vedas, particularly the Baghavad Gita, which I think is one of the great religious works of the world, and was the basis of Gandhi’s Hindu faith.

He knew a great deal about Christianity. He hated, by the way, the Old Testament. And I would say, well-he didn’t like the vengeance in it, the eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. But he missed the poetry. I mean, the poetry is there in the Old Testament. But he loved the New Testament, he could quote it backward and forward, and particularly the Sermon on the Mount. So I could never believe, as I was brought up to believe, and as many faiths in America teach, that Christianity was the only salvation. I couldn’t believe that 400 million Hindus, or 300 million, or several hundred million Buddhists wouldn’t go to heaven, or would go to Hell because they weren’t

Christians. You couldn’t believe that anymore. You absolutely couldn’t.

BILL MOYERS: Do you share any affinity with the idea that God died in this century, at Auschwitz and Buchenwald and in those trenches of Flanders?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: I ask myself, if there is a God, how could-and most people who believe in God, in a god -well, the Hindus have many gods -but if there is a God, how-say if there’s a Christian God, how could he permit Christians to slaughter 10 or 15 million people? If there is a Jewish God, how could he permit Christians to slaughter seven million Jews? And it’s a question which bothers me, and I can’t answer. It bothered me terribly.

BILL MOYERS: Is Tolstoy any help?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Yes, he’s been helpful to me, in a sense, because he went to Christianity -he learned Greek so he could understand the exact words of the New Testament -and he found a great deal of solace. Like Gandhi, he used to repeat the, you know, Sermon on the Mount, he knew it by heart. And he had some inner

[unintelligible]-he was a rather crotchety old man, too. And some of the things you can’t follow. But he did-he hoped, actually, to form a new form of Christianity, but that was beyond him and probably beyond any man. I know religion is a great solace. I’ve-it’s something that’s denied me at the present moment.

BILL MOYERS: Are you still looking?

WILLIAM L. SHIRER: Absolutely. Absolutely.

BILL MOYERS: [voice-over] From his home in Lenox, Massachusetts, this has been the conclusion of a conversation with William L. Shirer. I’m Bill Moyers.

This transcript was entered on March 26, 2015.