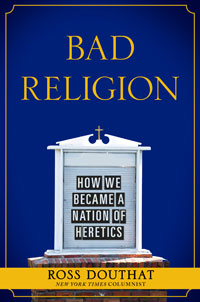

Televangelist and best-selling author, Joel Osteen, right, and his wife, Victoria, left. In his book Bad Religion, Ross Douthat calls Osteen's prosperity theology a heresy. (AP/Jessica Kourkounis)

Excerpted from Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics by Ross Douthat.

The most influential work of popular theology published this century comes with a glossy gold dust jacket and a slew of celebrity blurbs on the back. Celebrity Texan blurbs, mostly: Chuck Norris loved the book; so did the former NBA coach Rudy Tomjanovich; so did the then-owner of the Houston Astros, Drayton McLane; so did David Carr, the Houston Texans’ quarterback. The author himself gazes out from the front cover: his black hair is piled up and slick with gel; his hands are extended and touching at the fingertips; his smile is enormous, front teeth like piano keys or filed-down tusks. The book’s title hovers like an angel above his left shoulder, promising Your Best Life Now: 7 Steps to Living at Your Full Potential.

This is Joel Osteen, a Houston-based preacher who inherited a 7,500- seat megachurch from his late father, John Osteen, in 1999, and parlayed his pastorship into the highest-rated religious television show in America, a trio of #1 New York Times bestsellers, and a home for his congregation, Lakewood Church, in Houston’s 18,000-seat Compaq Center. In the fragmented landscape of American religion, Osteen comes as close to Billy Graham’s level of popularity and influence as any contemporary evangelist — and his cultural empire is arguably larger than Graham’s ever was. Your Best Life Now sold more than 4 million copies in the five years following its 2004 release, and it spawned a host of spin-offs — from Daily Readings from Your Best Life Now to a Your Best Life Now 2006 Journal and Daily Calendar. Its 2007 sequel, Become a Better You, followed a similar trajectory, in sales and spin-offs alike. Osteen’s weekly television show runs constantly on Daystar and the Trinity Broadcasting Network, both Christian channels — but also on network affiliates in all of the top thirty markets. (On a typical Sunday in Washington, D.C., in the mid-2000s, you could catch ten different showings of an Osteen service, on eight different channels.) Like Graham, Osteen courts a worldwide audience: More than 200 million people around the globe tune in to his broadcasts. And like Graham, he’s been known to sell out Madison Square Garden.

This is Joel Osteen, a Houston-based preacher who inherited a 7,500- seat megachurch from his late father, John Osteen, in 1999, and parlayed his pastorship into the highest-rated religious television show in America, a trio of #1 New York Times bestsellers, and a home for his congregation, Lakewood Church, in Houston’s 18,000-seat Compaq Center. In the fragmented landscape of American religion, Osteen comes as close to Billy Graham’s level of popularity and influence as any contemporary evangelist — and his cultural empire is arguably larger than Graham’s ever was. Your Best Life Now sold more than 4 million copies in the five years following its 2004 release, and it spawned a host of spin-offs — from Daily Readings from Your Best Life Now to a Your Best Life Now 2006 Journal and Daily Calendar. Its 2007 sequel, Become a Better You, followed a similar trajectory, in sales and spin-offs alike. Osteen’s weekly television show runs constantly on Daystar and the Trinity Broadcasting Network, both Christian channels — but also on network affiliates in all of the top thirty markets. (On a typical Sunday in Washington, D.C., in the mid-2000s, you could catch ten different showings of an Osteen service, on eight different channels.) Like Graham, Osteen courts a worldwide audience: More than 200 million people around the globe tune in to his broadcasts. And like Graham, he’s been known to sell out Madison Square Garden.

But there the similarities end. Graham’s persona was warm and inclusive, but theologically he preached a stark, stripped-down gospel — a series of altar calls, with eternity hanging in the balance and Christianity distilled to a yes or no for Christ. Osteen’s message is considerably more upbeat. His God gives without demanding, forgives without threatening to judge, and hands out His rewards in this life rather than in the next. Where Graham was inclined to comments like “we’re all on death row . . . the only way out of death row is Jesus,” Osteen prefers cheerier formulations. “Too many times we get stuck in a rut, thinking we’ve reached our limits,” he writes in Your Best Life Now. “But God wants us to constantly be increasing, to be rising to new heights. He wants to increase you in his wisdom and help you make better decisions. God wants to increase you financially, by giving you promotions, fresh ideas, and creativity.” And whereas Graham embodied evangelical Christianity’s shift back toward the Christian mainstream, and the beginning of its disassociation from fundamentalist separatism, Osteen embodies a shift of a very different sort— the refashioning of Christianity to suit an age of abundance, in which the old war between monotheism and money seems to have ended, for many believers, in a marriage of God and Mammon.

In the 1980s, this marriage was associated with hucksters and charlatans — preachers who robbed their followers, slept with prostitutes, and sobbed on camera. But in twenty-first-century America, the gospel of wealth has come of age. By linking the spread of the gospel to the habits and mores of entrepreneurial capitalism, and by explicitly baptizing the pursuit of worldly gain, prosperity theology has helped millions of believers reconcile their religious faith with their nation’s seemingly unbiblical wealth and un-Christian consumer culture.