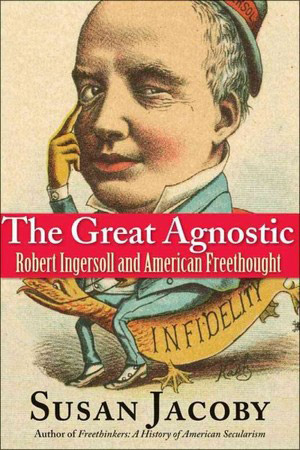

“It’s hard to exaggerate how famous he was in the last two decades of the 19th century,” our guest Susan Jacoby says of Robert Ingersoll, the subject of her new book, The Great Agnostic: Robert Ingersoll and American Freethought. But Ingersoll, once a “mover and shaker” in the Republican Party, is largely forgotten today. Why? He spoke out in favor of the separation of church and state and promoted Darwin’s theory of evolution, and because of that, could never run for public office. Ingersoll’s ideas were as controversial then as they are now.

[D]ivided response to Ingersoll at the end of the century was ignited not only by the continuing tension between religious power in American society and legal separation of church and state but also by the expanding influence of secularism even among the religious. In this respect, the religious landscape of the United States during the Gilded Age was not dissimilar from our own: the influence of biblically literal evangelicalism was growing even as mainstream Protestantism struggled to accommodate science and modernism by viewing the stories in both the Christian and Jewish Bibles in a metaphoric rather than a literal sense.

[D]ivided response to Ingersoll at the end of the century was ignited not only by the continuing tension between religious power in American society and legal separation of church and state but also by the expanding influence of secularism even among the religious. In this respect, the religious landscape of the United States during the Gilded Age was not dissimilar from our own: the influence of biblically literal evangelicalism was growing even as mainstream Protestantism struggled to accommodate science and modernism by viewing the stories in both the Christian and Jewish Bibles in a metaphoric rather than a literal sense.

In the nineteenth century, despite the much stronger influence of Protestantism and the growing influence of Catholicism, the formidable nature of the challenge posed by contemporary science, especially biology and geology, to biblical literalism may be inferred from the fact that the young William Jennings Bryan, while a student at Illinois College, wrote a letter to Ingersoll asking for his advice about dealing with the emerging contradictions between his education and his faith. This approach by Bryan to Ingersoll is not entirely surprising, since Bryan was born in 1860 in Marion County, Illinois, where Ingersoll, like Lincoln, began his career as a lawyer.

By the time Bryan was a college student in the 1870s, Ingersoll had also begun his career as an opponent of organized religion.* The man who would one day be known as “the great commoner” had heard the great agnostic speak, although Bryan himself would follow the more histrionic and sentimental style of evangelical preachers, better suited to his message than Ingersoll’s matter-of-fact way of speaking to an audience.

The connection between old-time religion and politics, however, was the reverse of today’s close relationship between religion and economic conservatism. Bryan was the leader of the entwined forces of economic and religious populism until his death in 1925 (shortly after the Scopes trial). His famous 1896 “cross of gold” speech had embodied the philosophical linkage between turn-of-the-century evangelical religion and the desire for economic (though not racial) justice.

Bryan would undoubtedly have been astonished had someone told him in the 1890s that a century in the future, Americans who upheld the literal truth of Genesis would be equally committed to the idea that the rich should pay lower taxes and that corporations should be treated as people.

The great religious and political paradox of the golden age of freethought was that even as the proportion of freethinkers and “religious liberals” increased, politicians were required to pay greater obeisance to religion than they had been either in the founding generation or at various earlier points in the nineteenth century. President Andrew Jackson, at a time when Paine’s reputation had been obliterated except among freethinkers, declared that “Thomas Paine needs no monument made with hands” because he “has erected a monument in the hearts of all lovers of liberty.” Lincoln—unlike William McKinley during the Spanish-American War—had explicitly rejected the claim that “God is on our side” during the Civil War.

He pointedly observed in his Second Inaugural Address that both sides “read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes his aid against the other,” adding that the prayers of both the North and the South could not be answered and that neither had been answered fully. For Ingersoll, the primary danger of entanglement between religion and politics was that invoking divine authority would simply shut down discussion on controversial issues. The requirement that politicians be religious, or at least appear to be religious, ruled out a significant group of independent thinkers from office. Ingersoll decried the public religiosity required of politicians in a statement that is just as applicable today as it was then.

At present, the successful office-seeker is a good deal like the centre of the earth; he weighs nothing himself, but draws everything else to him. There are so many societies, so many churches, so many isms, that it is almost impossible for an independent man to succeed in a political career. Candidates are forced to pretend that they are Catholics with Protestant proclivities, or Christians with liberal tendencies, or temperance men who now and then take a glass of wine, or, that although not members of any church their wives are, and that they subscribe liberally to all.

The result of all this is that we reward hypocrisy and elect men entirely destitute of real principle; and this will never change until the people become grand enough to do their own thinking.

* Ingersoll apparently never answered the letter, although his correspondence contains many personal replies to inquiries like Bryan’s. One can only wonder if a direct engagement with Ingersoll would have altered the mindset that produced Bryan’s lifelong commitment to the defense of literal biblical faith.