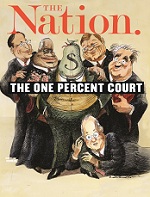

Jamie Raskin is a state senator in Maryland representing Silver Spring and Takoma Park and a constitutional law professor at American University. He introduced SB 690, which became the first Benefit Corporation law in America last year. A version of this essay will appear in an upcoming issue of The Nation, focusing on The Supreme Court that hits newsstands on Sept. 20, 2012.

“And may the odds be ever in your favor.”

“And may the odds be ever in your favor.”

—Effie Trinket, announcer for the corporate state in The Hunger Games

We live in what will surely come to be called the Citizens United era, a period in which a runaway corporatist ideology has overtaken Supreme Court jurisprudence. No longer content just to pick a president, as five conservative Republicans on the Rehnquist Court did back in 2000, five conservative Republicans on the Roberts Court a decade later voted to tilt the nation’s entire political process toward the views of moneyed corporate power.

In Citizens United (2010), the court held that private corporations, which are nowhere mentioned in the Constitution and are not political membership organizations, enjoy the same political free speech rights as people under the First Amendment and may draw on the wealth of their treasuries to spend unlimited sums promoting or disparaging candidates for public office. The billions of dollars thus turned loose for campaign purposes at the direction of corporate managers not only can be, but — under the terms of corporate law — must be spent to increase profits. If businesses choose to exercise their newly minted political “money speech” rights, they must work to install officials who will act as corporate tools.

The court, transformed by the addition of Chief Justice Roberts and Samuel Alito, who were nominated by that lucky winner in Bush v. Gore, took this giant step to the right of all prior courts without even being asked to do so. The petitioner, Citizens United, sought only a ruling that the electioneering provisions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (better known as McCain-Feingold) didn’t apply to its on-demand movie about Hillary Clinton. But the conservatives sent the parties back to brief and argue the paradigm-shifting constitutional question they were so keen to decide. As dissenting Justice John Paul Stevens observed, the justices in the majority “changed the case to give themselves an opportunity to change the law.”

Before Citizens United came down, corporations were already spending billions of dollars lobbying, running “issue ads,” launching political action committees and soliciting PAC contributions. Moreover, CEOs, top executives and board directors — the people whose income and wealth have soared over the past several decades in relation to the rest of America — have always contributed robustly to candidates. But there was one crucial thing that CEOs could not do before Citizens United: reach into their corporate treasuries to bankroll campaigns promoting or opposing the election of candidates for Congress or president. This prohibition essentially established a wall of separation — not especially thick or tall, but a wall nonetheless — between corporate treasury wealth and campaigns for federal office.

The Roberts Court’s 5-4 decision to demolish most of this wall also bulldozed the foundational understanding of the corporation that had governed American law for two centuries. The court had always regarded the corporation not as a citizen with constitutional rights, but as an “artificial entity” chartered by the states and endowed with extraordinary privileges in order to serve society’s economic purposes. The great conservative Chief Justice John Marshall wrote in the Dartmouth College case (1819), “A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law. Being the mere creature of law, it possesses only those properties which the charter of creation confers upon it, either expressly, or as incidental to its very existence.”

This “artificial entity” understanding of corporate law prevailed until Big Tobacco lawyer and corporate-state visionary Lewis Powell, of Richmond, Virginia, joined the court. In First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti (1978), the key forerunner to Citizens United, Powell assembled a bare majority to give corporations and banks the right to spend without limit to influence public opinion in ballot issue campaigns. The decision, which approved the desire of banks in Massachusetts to campaign against progressive tax measures, unveiled the key doctrinal move of what would later become the Citizens United era: “If the speakers here were not corporations, no one would suggest that the state could silence their proposed speech,” Justice Powell wrote. “The inherent worth of the speech in terms of its capacity for informing the public does not depend upon the identity of its source.”

The Bellotti decision cracked open the door of campaign finance law, and the Citizens United majority blew that door off its hinges. The Court announced that, when it comes to campaign spending rights, the “identity of the speaker” is irrelevant and an impermissible basis upon which to repress the flow of money speech. What matters is the “speech” itself, never the speaker — a doctrine that would have come in handy for the public employees, public school students, whistleblowers, prisoners and minor-party candidates whose free-speech rights have been crushed by the conservative court because of their identity as (disfavored) speakers.

Taken seriously, the Citizens United doctrine has astonishing implications for campaign finance. If it’s true that the “identity of the speaker” is irrelevant, the City of New York — a municipal corporation, after all — should have a right to spend money telling residents whom to vote for in mayoral races. Maryland could spend tax dollars urging citizens to vote for marriage equality in November, and President Obama could order the Government Printing Office to produce a book advocating his re-election. Surely the Supreme Court would never ban a book containing campaign speech!

Furthermore, under the new doctrine, churches — religious corporations — would have a First Amendment right not only to promote candidates from the pulpit but to spend freely on television ads advocating their election or trashing their opponents. The claim that churches surrender their right to engage in electioneering when they accept 501(c)(3) status is obsolete after Citizens United, which rejected the view that groups can be divested of their right to participate in politics when they receive incorporated status and special legal and financial privileges. If the identity of the speaker is truly irrelevant, there should be nothing to stop the Church of Latter-Day Saints or Harvard University from bankrolling political campaigns.

In the real world, the claim that the identity of the speaker is irrelevant cannot be taken seriously, and it is already being disregarded by the justices who signed on to it. The court has so far declined to strike down the ban on foreign corporate spending in American politics and the century-old ban on direct corporate contributions to candidates, laws that the new doctrine logically should invalidate. A total wipeout of campaign finance law appears to be just a step too far — at least right now — for a court already facing plummeting public legitimacy.

But even if this incoherent doctrine goes no further, the surging stream of corporate and billionaire spending has already made a sweet difference for the Republican Party, which despairs of the nation’s demographic and cultural changes and depends on a mix of right-wing propaganda and voter suppression to confuse and shrink the electorate. Indeed, the potency of Citizens United became clear in the same year the decision was released.