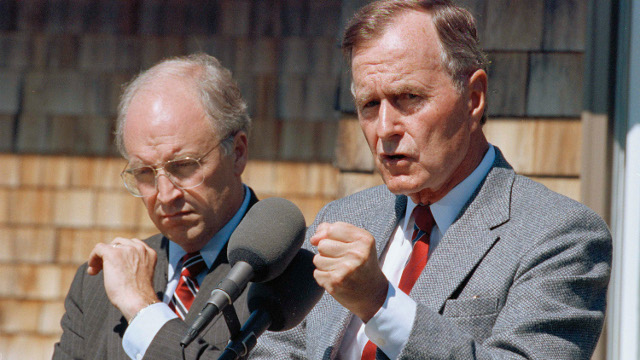

President George HW Bush and Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney in Kennebunkport, Maine, in 1990. (Image: Doug Mills/ AP)

Polls suggest that Americans tend to differentiate between our “good war” in Iraq — “Operation Desert Storm,” launched by George HW Bush in 1990 — and the “mistake” his son made in 2003.

Across the ideological spectrum, there’s broad agreement that the first Gulf War was “worth fighting.” The opposite is true of the 2003 invasion, and a big reason for those divergent views was captured in a 2013 CNN poll that found that “a majority of Americans (54%) say that prior to the start of the war the administration of George W. Bush deliberately misled the U.S. public about whether Baghdad had weapons of mass destruction.”

But as the usual suspects come out of the woodwork to urge the US to once again commit troops to Iraq, it’s important to recall that the first Gulf War was sold to the public on a pack of lies that were just as egregious as those told by the second Bush administration 12 years later.

The Lie of an Expansionist Iraq

Most countries condemned Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. But the truth — that it was the culmination of a series of tangled economic and historical conflicts between two Arab oil states — wasn’t likely to sell the US public on the idea of sending our troops halfway around the world to do something about it.

So we were given a variation of the “domino theory.” Saddam Hussein, we were told, had designs on the entire Middle East. If he wasn’t halted in Kuwait, his troops would just keep going into other countries.

As Scott Peterson reported for The Christian Science Monitor in 2002, a key part of the first Bush administration’s case “was that an Iraqi juggernaut was also threatening to roll into Saudi Arabia. Citing top-secret satellite images, Pentagon officials estimated in mid-September [of 1990] that up to 250,000 Iraqi troops and 1,500 tanks stood on the border, threatening the key US oil supplier.”

A quarter of a million troops with heavy armor amassed on the Saudi border certainly seemed like a clear sign of hostile intent. In announcing that he had deployed troops to the Gulf in August 1990, George HW Bush said, “I took this action to assist the Saudi Arabian Government in the defense of its homeland.” He asked the American people for their “support in a decision I’ve made to stand up for what’s right and condemn what’s wrong, all in the cause of peace.”

But one reporter — Jean Heller of the St. Petersburg Times — wasn’t satisfied taking the administration’s claims at face value. She obtained two commercial satellite images of the area taken at the exact same time that American intelligence supposedly had found Saddam’s huge and menacing army and found nothing there but empty desert.

She contacted the office of then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney “for evidence refuting the Times photos or analysis offering to hold the story if proven wrong.” But “the official response” was: “Trust us.”

Heller later told the Monitor’s Scott Peterson that the Iraqi buildup on the border between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia “was the whole justification for Bush sending troops in there, and it just didn’t exist.”

Dead Babies, Courtesy of a New York PR Firm

Military occupations are always brutal, and Iraq’s six-month occupation of Kuwait was no exception. But because Americans didn’t have an abundance of affection for Kuwait, a case had to be built that the Iraqi army was guilty of nothing less than Nazi-level atrocities.

That’s where a hearing held by the Congressional Human Rights Caucus in October 1990 played a major role in making the case for war.

A young woman who gave only her first name, Nayira, testified that she had been a volunteer at Kuwait’s al-Adan hospital, where she had seen Iraqi troops rip scores of babies out of incubators, leaving them “to die on the cold floor.” Between tears, she described the incident as “horrifying.”

Her account was a bombshell. Portions of her testimony were aired that evening on ABC’s “Nightline” and NBC’s “Nightly News.” Seven US senators cited her testimony in speeches urging Americans to support the war, and George HW Bush repeated the story on 10 separate occasions in the weeks that followed.

In 2002, Tom Regan wrote about his own family’s response to the story for The Christian Science Monitor:

I can still recall my brother Sean’s face. It was bright red. Furious. Not one given to fits of temper, Sean was in an uproar. He was a father, and he had just heard that Iraqi soldiers had taken scores of babies out of incubators in Kuwait City and left them to die. The Iraqis had shipped the incubators back to Baghdad. A pacifist by nature, my brother was not in a peaceful mood that day. “We’ve got to go and get Saddam Hussein. Now,” he said passionately.

Subsequent investigations by Amnesty International, a division of Human Rights Watch and independent journalists would show that the story was entirely bogus — a crucial piece of war propaganda the American media swallowed hook, line and sinker. Iraqi troops had looted Kuwaiti hospitals, but the gruesome image of babies dying on the floor was a fabrication.

In 1992, John MacArthur revealed in The New York Times that Nayirah was in fact the daughter of Saud Nasir al-Sabah, Kuwait’s ambassador to the US. Her testimony had been organized by a group called Citizens for a Free Kuwait, which was a front for the Kuwaiti government.

Tom Regan reported that Citizens for a Free Kuwait hired Hill & Knowlton, a New York-based PR firm that had previously spun for the tobacco industry and a number of governments with ugly human rights records. The company was paid “$10.7 million to devise a campaign to win American support for the war.” It was a natural fit, wrote Regan. “Craig Fuller, the firm’s president and COO, had been then-President George Bush’s chief of staff when the senior Bush had served as vice president under Ronald Reagan.”

According to Robin Andersen’s A Century of Media, a Century of War, Hill & Knowlton had spent $1 million on focus groups to determine how to get the American public behind the war, and found that focusing on “atrocities” was the most effective way to rally support for rescuing Kuwait.

Arthur Rowse reported for the Columbia Journalism Review that Hill & Knowlton sent out a video news release featuring Nayirah’s gripping testimony to 700 American television stations.

As Tom Regan noted, without the atrocities, the idea of committing American blood and treasure to save Kuwait just “wasn’t an easy sell.”

Only a few weeks before the invasion, Amnesty International accused the Kuwaiti government of jailing dozens of dissidents and torturing them without trial. In an effort to spruce up the Kuwait image, the company organized Kuwait Information Day on 20 college campuses, a national day of prayer for Kuwait, distributed thousands of “Free Kuwait” bumper stickers, and other similar traditional PR ventures. But none of it was working very well. American public support remained lukewarm the first two months.

That would change as stories about Saddam’s baby-killing troops were splashed across front pages across the country.

Saddam Was Irrational

Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait was just as illegal as the US invasion that would ultimately oust him 13 years later — it was neither an act of self-defense, nor did the UN Security Council authorize it.

But it can be argued that Iraq had significantly more justification for its attack.

Kuwait had been a close ally of Iraq, and a top financier of the Iraqi invasion of Iran in 1980, which, as The New York Times reported, occurred after “Iran’s revolutionary government tried to assassinate Iraqi officials, conducted repeated border raids and tried to topple Mr. Hussein by fomenting unrest within Iraq.”

Saddam Hussein felt that Kuwait should forgive part of his regime’s war debt because he had halted the “expansionist plans of Iranian interests” not only on behalf of his own country, but in defense of the other Gulf Arab states as well.

After an oil glut knocked out about two-thirds of the value of a barrel of crude oil between 1980 and 1986, Iraq appealed to OPEC to limit crude oil production in order to raise prices — with oil as low as $10 per barrel, the government was struggling to pay its debts. But Kuwait not only resisted those efforts — and asked OPEC to increase its quotas by 50 percent instead — for much of the 1980s it also had maintained its own production well above OPEC’s mandatory quota. According to a study by energy economist Mamdouh Salameh, “between 1985 and 1989, Iraq lost US$14 billion a year due to Kuwait’s oil price strategy,” and “Kuwait’s refusal to decrease its oil production was viewed by Iraq as an act of aggression against it.”

There were additional disputes between the two countries centering on Kuwait’s exploitation of the Rumaila oil fields, which straddled the border between the two countries. Kuwait was accused of using a technique known as “slant-drilling” to siphon off oil from the Iraqi side.

None of this justifies Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. But a longstanding and complex dispute between two undemocratic petrostates wasn’t likely to inspire Americans to accept the loss of their sons and daughters in a distant fight.

So instead, George HW Bush told the public that Iraq’s invasion was “without provocation or warning,” and that “there is no justification whatsoever for this outrageous and brutal act of aggression.” He added: “Given the Iraqi government’s history of aggression against its own citizens as well as its neighbors, to assume Iraq will not attack again would be unwise and unrealistic.”

Ultimately, these longstanding disputes between Iraq and Kuwait got considerably less attention in the American media than did tales of Kuwaiti babies being ripped out of incubators by Saddam’s stormtroopers.

Saddam Was “Unstoppable”

A crucial diplomatic error on the part of the first Bush administration left Saddam Hussein with the impression that the US government had little interest in Iraq’s conflict with Kuwait. But that didn’t fit into the narrative that the Iraqi dictator was an irrational maniac bent on regional domination. So there was a concerted effort to deny that the US government had ever had a chance to deter his aggression through diplomatic means — and even to paint those who said otherwise as conspiracy theorists.

As John Mearsheimer from the University of Chicago and Harvard’s Stephen Walt wrote in 2003, “Saddam reportedly decided on war sometime in July 1990, but before sending his army into Kuwait, he approached the United States to find out how it would react.”

In a now famous interview with the Iraqi leader, U.S. Ambassador April Glaspie told Saddam, “[W]e have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.” The U.S. State Department had earlier told Saddam that Washington had “no special defense or security commitments to Kuwait.” The United States may not have intended to give Iraq a green light, but that is effectively what it did.

Exactly what was said during the meeting has been a source of some controversy. Accounts differ. According to a transcript released by the Iraqi government, Glaspie told Hussein, ” I admire your extraordinary efforts to rebuild your country.”

I know you need funds. We understand that and our opinion is that you should have the opportunity to rebuild your country. But we have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.

I was in the American Embassy in Kuwait during the late 60’s. The instruction we had during this period was that we should express no opinion on this issue and that the issue is not associated with America. James Baker has directed our official spokesmen to emphasize this instruction.

Leslie Gelb of The New York Times reported that Glaspie told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the transcript was inaccurate “and insisted she had been tough.” But that account was contradicted when diplomatic cables between Baghdad and Washington were released. As Gelb described it, “The State Department instructed Ms. Glaspie to give the Iraqis a conciliatory message punctuated with a few indirect but significant warnings,” but “Ms. Glaspie apparently omitted the warnings and simply slobbered all over Saddam in their meeting on July 25, while the Iraqi dictator threatened Kuwait anew.”

There is no dispute about one crucially important point: Saddam Hussein consulted with the US before invading, and our ambassador chose not to draw a line in the sand, or even hint that the invasion might be grounds for the US to go to war.

The most generous interpretation is that each side badly misjudged the other. Hussein ordered the attack on Kuwait confident that the US would only issue verbal condemnations. As for Glaspie, she later told The New York Times, ”Obviously, I didn’t think — and nobody else did — that the Iraqis were going to take all of Kuwait.”

Fool Me Once…

The first Gulf War was sold on a mountain of war propaganda. It took a campaign worthy of George Orwell to convince Americans that our erstwhile ally Saddam Hussein — whom the US had aided in his war with Iran as late as 1988 — had become an irrational monster by 1990.

Twelve years later, the second invasion of Iraq was premised on Hussein’s supposed cooperation with al Qaeda, vials of anthrax, Nigerian yellowcake and claims that Iraq had missiles poised to strike British territory in little as 45 minutes.

Now, eleven years later, as Bill Moyers put it last week, “the very same armchair warriors in Washington who from the safety of their Beltway bunkers called for invading Baghdad, are demanding once again that America plunge into the sectarian wars of the Middle East.” It’s vital that we keep our history in Iraq in mind, and apply some healthy skepticism to the claims they offer us this time around.