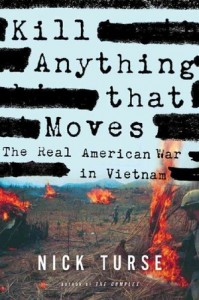

Read the introduction from Nick Turse’s book, Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam.

On Jan. 21, 1971, a Vietnam veteran named Charles McDuff wrote a letter to President Richard Nixon to voice his disgust with the American war in Southeast Asia. McDuff had witnessed multiple cases of Vietnamese civilians being abused and killed by American soldiers and their allies, and he had found the US military justice system to be woefully ineffective in punishing wrongdoers. “Maybe your advisors have not clued you in,” he told the president, “but the atrocities that were committed in Mylai are eclipsed by similar American actions throughout the country.” His three-page handwritten missive concluded with an impassioned plea to Nixon to end American participation in the war.

The White House forwarded the note to the Department of Defense for a reply, and within a few weeks Major General Franklin Davis Jr., the army’s director of military personnel policies, wrote back to McDuff. It was “indeed unfortunate,” said Davis, “that some incidents occur within combat zones.” He then shifted the burden of responsibility for what had happened firmly back onto the veteran. “I presume,” he wrote, “that you promptly reported such actions to the proper authorities.” Other than a paragraph of information on how to contact the US Army criminal investigators, the reply was only four sentences long and included a matter-of-fact reassurance: United States Army has never condoned wanton killing or disregard for human life.”

This was, and remains, the American military’s official position. In many ways, it remains the popular understanding in the United States as a whole. Today, histories of the Vietnam War regularly discuss war crimes or civilian suffering only in the context of a single incident: the My Lai massacre cited by McDuff. Even as that one event has become the subject of numerous books and articles, all the other atrocities perpetrated by US soldiers have essentially vanished from popular memory. The visceral horror of what happened at My Lai is undeniable.

On the evening of March 15, 1968, members of the Americal Division’s Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, were briefed by their commanding officer, Captain Ernest Medina, on a planned operation the next day in an area they knew as “Pinkville.” As unit member Harry Stanley recalled, Medina “ordered us to ‘kill everything in the village.'” Infantryman Salvatore LaMartina remembered Medina’s words only slightly differently: they were to “kill everything that breathed.” What stuck in artillery forward observer James Flynn’s mind was a question one of the other soldiers asked: “Are we supposed to kill women and children?” And Medina’s reply: “Kill everything that moves.”

The next morning, the troops clambered aboard helicopters and were airlifted into what they thought would be a “hot LZ”— a landing zone where they’d be under hostile fire. As it happened, though, instead of finding Vietnamese adversaries spoiling for a fight, the Americans entering My Lai encountered only civilians: women, children and old men. Many were still cooking their breakfast rice. Nevertheless, Medina’s orders were followed to a T. Soldiers of Charlie Company killed. They killed everything. They killed everything that moved.

Advancing in small squads, the men of the unit shot chickens as they scurried about, pigs as they bolted and cows and water buffalo lowing among the thatch-roofed houses. They gunned down old men sitting in their homes and children as they ran for cover. They tossed grenades into homes without even bothering to look inside. An officer grabbed a woman by the hair and shot her point-blank with a pistol. A woman who came out of her home with a baby in her arms was shot down on the spot. As the tiny child hit the ground, another GI opened up on the infant with his M-16 automatic rifle.

Over four hours, members of Charlie Company methodically slaughtered more than 500 unarmed victims, killing some in ones and twos, others in small groups, and collecting many more in a drainage ditch that would become an infamous killing ground.

They faced no opposition. They even took a quiet break to eat lunch in the midst of the carnage. Along the way, they also raped women and young girls, mutilated the dead, systematically burned homes and fouled the area’s drinking water.