This post originally appeared on TomDispatch.

They don’t call it the “cliff” for nothing. It’s the fiscal spot where a nation’s representatives can gather and cry doom. It’s the place — if Washington is to be believed — where, with a single leap into the Abyss of Sequestration, those representatives can end it all for the rest of us.

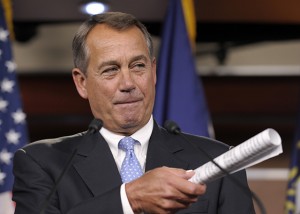

House Speaker John Boehner of Ohio speaks to reporters during a news conference on Capitol Hill, Friday, Nov. 9. Boehner said any deal to avert the so-called fiscal cliff should include lower tax rates, eliminating special interest loopholes and revising the tax code. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

As a start, relax. Don’t let the headlines get to you. There’s little reason for anyone to lose sleep over the much-hyped fiscal cliff. In fact, if you were choosing an image based on the coming fiscal dust-up, it probably wouldn’t be a cliff but an obstacle course — a series of federal spending cuts and tax increases all scheduled to take effect as 2013 begins. And it’s true that, if all those budget cuts and tax increases were to go into effect at the same time, an already weak recovery would probably sink into a double-dip recession.

But ignore the sound and fury. While prophecy is usually a perilous occupation, in this case it’s pretty easy to predict how lawmakers will deal with nearly every challenge on the president’s and Congress’s end-of-year obstacle course. The upshot? The U.S. economy isn’t headed over a cliff any time soon.

Sequestering Congress

A peek at the obstacles ahead makes that clear.

Across-the-board spending cuts threaten to shave roughly 9% from discretionary spending in the federal budget. Those cuts, known in Washington parlance as “sequestration,” are the results of an agreement between Congress and the president and are scheduled to take effect on January 2nd. If they were to actually happen, they would reduce Pentagon spending, as well as funding for a vast array of domestic programs ranging from cancer research and food safety to grants for disadvantaged public schools.

For different reasons, neither Democrats nor Republicans want sequestration to happen — and it was never intended to. It was originally meant as a threat so terrible that lawmakers would hammer out a bipartisan, deficit-reducing budget compromise to avoid it. The very fact that sequestration is now in the pipeline crystalizes what’s wrong in Washington — and to understand how lawmakers will deal with it, a back story is needed.

Last August, a group of House Republican lawmakers nearly refused to raise the debt ceiling — the limit Congress places on its own borrowing — even though failing to do so would have shut down the government and raised interest rates for everyone. As part of a last-second bargain-basement deal to avert that disaster, Congress agreed to one dollar of deficit reduction for every dollar added to the debt ceiling. Lawmakers settled on a debt ceiling $2.4 trillion higher and deficits $2.4 trillion lower over 10 years. In other words, they wrote into law a purely arbitrary level of deficit reduction. It had nothing to do with what the best available experts believed about how soon and how much to reduce deficits.

On top of that, the lawmakers didn’t actually decide how they’d achieve all that deficit reduction. They simply dumped that little detail on a 12-member “super committee” of Republican and Democratic House and Senate members. Predictably, the committee proved something less than “super,” failing at the task — a failure that, according to the August deal, was to trigger those automatic cuts.

Ever since, lawmakers of both parties have been warning with increasing desperation and fervor — the Republicans because of Pentagon spending, the Democrats because of domestic programs — that disaster, if not world-ending catastrophe, is now in the wings ready to strike unless someone does something. The irony should not be lost that these are, of course, the very lawmakers who wrote sequestration into law in the first place.

In recent months, it has come to light that sequestration could lead to the loss of more than two million jobs — from schoolteachers to young people working for AmeriCorps. Defense hawks in particular have gone wild over very public and strategic threats of layoffs by various giant defense corporations. The reality is that your local high school will have a far tougher time sustaining budget cuts than the Pentagon, which is well-fortified to survive more than its share of reductions. After all, in the post-2001 decade Pentagon spending grew by a staggering 48% (after inflation). And war funding would be exempt from any cuts.

But sequestration is loathed by both parties, and that makes it easy to predict one thing: it won’t happen. The lame-duck Congress will likely do what it’s best at. It will punt sequestration down the road — a safe bet is six months — dumping it in the lap of the new Congress. In a perfect world, Congress would simply cancel sequestration as part of an intelligent plan to replace across-the-board cuts with a measured, long-term approach to deficit reduction. But don’t bet on that. The only safe wager is that Congress will dodge sequestration.

The Obstacle of Obstacles in American Politics

Those across-the-board cuts are, however, just one hurdle on that post-election fiscal obstacle course landscape. Let’s tour the rest.

On December 31st, the Bush-era tax cuts are scheduled to expire, returning rates to Clinton-era levels. They include tax breaks for just about everyone, but for our purposes, let’s break the package into two parts: tax cuts for families making over $250,000 and individuals making over $200,000 annually, and those for everyone else. There’s already agreement across the aisle in Washington to retain the lower rates for the under-$250K crowd, so it’s a pretty safe bet that, in the end, middle-class families won’t actually see their income taxes rise. But what of tax cuts for the wealthy? We’ll get to those later. Let’s take care of a few other things first.

Two policies that were meant to buoy the economy during the recession are scheduled to expire at the end of the year: expanded unemployment compensation and a payroll-tax holiday. Expanded unemployment benefits extend a crucial lifeline to the jobless. What’s more, unemployment insurance is one of the most efficient ways for the government to strengthen a weak economy, since unemployed people, unlike those with a lot of money, spend extra cash immediately and pump that money into the economy. Moody’s Analytics, a risk-management firm, and the non-partisan Congressional Research Service recently affirmed this wisdom.

Unfortunately, Congress will get stuck on this part of the obstacle course. Federal unemployment benefits will likely expire. So will the payroll-tax holiday, a temporary reduction in the Social Security tax paid by workers. This will indeed be bad for the economy, but it’s not a cliff. What’s important about these changes is they will hurt a small group of the most vulnerable Americans — the people who have already been hardest hit.

Once again, it’s all about politics, not about the stuff that actually matters — a reality that becomes more obvious with the next two obstacles. There’s a bundle of expiring provisions in the tax code — known esoterically as “tax extenders” and the Alternative Minimum Tax “patch“– that benefit corporations and upper-middle class Americans, respectively. Congress will likely extend these expiring provisions without much discussion, just as they’ve done in the past.

Next obstacle: health care. The Affordable Care Act — Obamacare — includes a handful of new taxes that will go live in 2013. These will affect high-income Americans and some of the medical industry, like medical-device manufacturers. These taxes will likely go into effect right on schedule, but they’re so small they’ll have next to no discernible impact on the economy. (The more controversial taxes and fees in Obamacare go into effect in 2014.)

Also in the queue is a massive pay cut for doctors who serve Medicare patients. That scheduled change is the result of legislation originally passed in 1997. It’s something that lawmakers have repeatedly managed to avoid, and it’s not a daring prediction that they’ll do so again.

And then there’s the twenty-first century obstacle of obstacles in American politics: the Bush-era tax cuts for the high-income set. President Obama has said he will veto any legislation that keeps them in place, while Republicans in Congress insist that extending them must be part of any deal to maintain low rates for everyone else.

Among all the spending and tax changes in the queue, and all the hype around the cliff, the great unknown is whether it’s finally farewell to the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy. And that’s no perilous cliff. Letting those high-end tax cuts expire would amount to a blink-and-you-miss-it 0.003% contraction in the U.S. economy, according to Moody’s, and it would raise tens of billions of dollars in desperately-needed tax revenue next year. That’s no small thing when you consider that federal revenue has fallen to its lowest point in more than half a century. Ending these tax cuts for the wealthy would bring in cash to reduce deficits or increase funding for cash-starved priorities like higher education.

It’s impossible to say how Congress will come down on this final issue, though we do know how lawmakers will arrive at their decision. At least Congress is consistent. On this, as on all other matters in the fiscal obstacle course, it’s not the economy.

It’s the politics, stupid.

See more thoughts on the Fiscal Cliff in our new Group Think feature, “What to Do About the Fiscal Cliff,” in which a variety of thinkers respond to the crisis.

Mattea Kramer and Chris Hellman are research analysts at the National Priorities Project. Both TomDispatch regulars, they coauthored the new book A People’s Guide to the Federal Budget. Kramer answered questions about the the Ryan budget in August.