In 2013, we named Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II an “activist to watch” as he kicked off his Moral Monday movement — a multiracial, multi-issue movement centered around social justice. A few months later, he figured prominently in our short film about North Carolina that chronicled the battle going on in that state between right-wing politicians in charge of the government, and citizen activists, led by Rev. Dr. Barber.

Shortly after the election of Donald Trump, Barber wrote for this site that the challenge America faces is no less than a Third Reconstruction. “The story of our struggle for freedom is not linear: Every advance toward a more perfect union has been met with a backlash of resistance.”

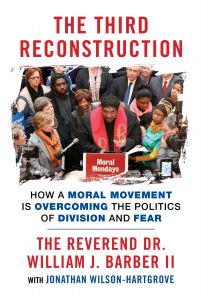

In this excerpt from his new book, The Third Reconstruction: How a Moral Movement Is Overcoming the Politics and Division of Fear, Barber documents the fight to sustain the gains of the Second Reconstruction of the Civil Rights Movement and the struggle to make progress. As president of the North Carolina NAACP, Barber has come up against the backlash of resistance in its more vicious forms — a rollback of voting rights and institutionalized prejudice. The story of the Moral Monday movement is the new Civil Rights Era made manifest — a first foray in the Third Reconstruction.

— Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, 2016

WITH NO POLITICAL OPPOSITION to check their power, the extremists in North Carolina joined hands to remake our state in 2013. In their minds, it was the perfect test case for the comprehensive blueprint ALEC had developed. Thom Tillis, a former ALEC board member, was speaker of the North Carolina House. Phil Berger, an ultraconservative, was leading the state Senate. And Pat McCrory had just been elected governor with the full support of Art Pope’s extremist machine. As an indication of just how deeply aligned with the extremism he was, McCrory appointed Pope the state budget director. The man who had both plotted and funded this 21st-century coup was now controlling North Carolina’s purse strings.

It didn’t take long for this quadrumvirate to put its cards on the table. They introduced legislation to block the expansion of Medicaid to half a million North Carolinians and cut off federal unemployment benefits for 170,000 of our unemployed sisters and brothers. Echoing the interposition of federally mandated integration the 1960s, which led Alabama’s Gov. George Wallace to block the door of the University of Alabama to African-American students, both moves were intended to deny North Carolinians access to federal benefits they had already been granted. The very politicians who had campaigned for an “economic comeback” were blocking the flow of millions of dollars into our state’s economy on ideological grounds.

But they didn’t stop there. They introduced a bill to overturn our Racial Justice Act. They moved to end public financing for judicial elections (which would allow them to buy off judges to influence them to refuse our challenges to their unconstitutional actions in court). They wrote a new tax code for the state, throwing out the earned-income tax credit (which helped nearly a million working families) while impoverishing the state by slashing taxes for the most wealthy. They introduced a bill that would allow people to buy guns without a permit and carry them in public parks and restaurants.

But they didn’t stop there, either. There was, after all, no political foe to stop them from unleashing every fear they had stoked and each division they’d leveraged into a wedge issue. When Mr. Pope’s budget was presented to the General Assembly, it included the same unconstitutional cuts to pre-K education against which we had won an injunction in court. What’s more, Pope’s budget proposed shifting $90 million of public funds to private schools through vouchers. At a stroke it eliminated entire state-funded agencies, such as Legal Aid, that provide constitutionally protected legal assistance to prisoners. Meanwhile, it proposed raises for the so-called conservatives Gov. McCrory had hired to oversee North Carolina’s economic “comeback.”

Finally, on top of this full slate of extremist legislation, they introduced their “monster” voter-suppression bill during the week of March 9, when we in the freedom movement remember Bloody Sunday and all those who bled and died for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. We called it a monster bill from the beginning, for two reasons: First, its scope was monstrous, ranging from restrictions that would require a state-issued photo ID (which 318,000 registered voters didn’t have) to drastic cuts in early voting. It would eliminate same-day registration, take away the automatic restoration of voting rights for ex-felons, and end the child-dependency tax deduction ($2,000 to $2,500 per child) for parents of college students who chose to vote where they attended school — in effect, a way of punishing the parents via the tax code for their children’s exercising the voting franchise. We called it a monster to help people see the hydra-like reach of this many-headed effort to suppress votes. But we also had to call it a monster because its obvious intent was as vicious as Bull Connor’s dogs in Birmingham and Sheriff Jim Clark’s billy clubs on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. By targeting voters who were students, poor people, the elderly, African-Americans and ex-felons, they were admitting that they knew a majority of us would not support their agenda and would try to vote them out of power. Nevertheless, they were going to carry it forward by any means necessary, doing everything in their power to make sure we could never vote them out of power.

We had beaten them back in 2008, when President Obama won North Carolina. But the extremists showed us during our Holy Week of 2013 that they were willing to do anything to make sure we never beat them again.

As a preacher, I saw what was happening in Raleigh that Holy Week through the lens of Jesus bearing his cross. When Jesus led his fusion coalition into Jerusalem that first Holy Week, it was a joyous occasion. Jerusalem greeted him as a king. But the governing elite reacted harshly, playing on dissention within the coalition’s ranks to buy off Judas and turn the crowds against Jesus. Just before he hung his head and died, a victim of the very worst that the powers can do to us, Jesus prayed, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” He loved his enemies to the very end, the Bible tells us, holding on to the moral center of his campaign, even in the face of death. When he died, the whole world went dark. Even still, a few from his movement held on.

I recalled a story from the Birmingham campaign of 1963, when Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference had come in to support the local desegregation effort. The year before, in Albany, Georgia, King had experienced what he considered a defeat in the battle against Police Chief Laurie Pritchett, who studied nonviolent tactics and concluded that the best way to diffuse them is to meet them nonviolently, avoiding the extremism that gives protestors the moral high ground. By refusing to get angry or react violently in public, Pritchett had avoided media attention and subverted King’s plan to integrate Albany by drawing outside attention to a violent confrontation.

But Birmingham’s Bull Connor had a record of extremism. If the movement pushed him hard enough, they knew he would expose the ugliness of Jim Crow. And they were right. Connor sent out the patrol wagons and arrested everyone the movement could find to march. But still, Birmingham wouldn’t budge. Once again it was Holy Week, and Dr. King was preparing to preach the story of Jesus, who had found another way to victory by laying down his life in love. Through the lens of the Easter story, King recognized that a moral movement must press on, even in its darkest hour, trusting the One who can make a way out of no way — believing that we find a way by pressing forward.

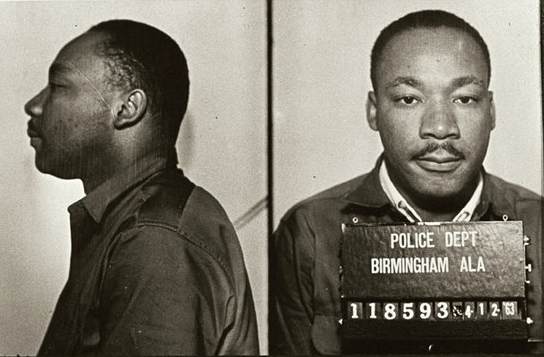

Dr. King excused himself from a planning meeting on that Good Friday and, according to his aides, came back wearing denim work clothes. He was dressed for jail. He would march against Connor’s orders and get arrested, he said, even though he did not know how it would advance the campaign. He was pressing forward into the darkness, trusting that a power beyond him would shine the light of truth on Birmingham’s dark hatred.

(Photo by Jim Forest/ flickr CC 4.0)

THAT EASTER WEEKEND in the Birmingham jail turned out to be Dr. King’s most famous direct action against segregation in the South. The letter he wrote from his cell went around the world, inspiring people of conscience and moral movements from South Africa to China. The Birmingham campaign was followed by the Children’s March, which grabbed the attention of the nation and precipitated the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But Dr. King didn’t know any of that when he decided to go to jail. He only knew that pressing forward in the way of truth, being willing to embrace unearned suffering, was the way of his Lord. He had learned from the great river of the Southern freedom movement that such a “faith act” is sometimes the only way forward.

As the avalanche of extremism continued to dump a mountain of despair on North Carolina 50 years later, our young people showed us that a new “faith act” was needed. When the monster voter-suppression bill came to the floor for debate, college students with duct tape covering their mouths filled the observation area, exposing how this wicked law sought to silence them. When the bill finally passed, on April 25, we knew the students had shown us the way, just as they had back in 1960 when they sat down at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, refusing to accept Jim Crow’s old assumptions. It was time for our faith act. I gathered with a core group of our coalition partners to plan.

We did not have to meet for long. Having journeyed together for seven years, we knew what we had to do. Frankly, it was a meeting not unlike the meetings we’d had for years — meetings we would continue to have, finding our way together. We did not think we were doing anything particularly profound when we decided that, on the following Monday, seventeen of us would exercise our constitutional right to instruct our legislators about the evil they were committing despite the fact that they refused to meet with us. The Rev. T. Anthony Spearman, whose prayer had scared the officer in the elevator two years earlier, was there. Nancy Petty and Tim Tyson, who’d gone to jail with me during the Wake County struggle, were there. Bob Zellner, who had stayed with our movement since winning John McNeil’s freedom, was there, too, reminding us what Rosa Parks had whispered in his ear back in Montgomery: “When you see something that’s wrong, eventually you have to do something about it.” We were a freedom family, doing what we had learned to do. We didn’t know where it would lead, but we knew we had to do everything in our power to expose the extremism that had become so normal in the daily news.

We were disappointed but not surprised when the extremists decided to arrest us rather than hear our petition. What did surprise me was the outpouring of support we witnessed as we came out of jail early that next morning. After watching our arrests on the news, hundreds of people called, emailed and even came down to the jail to ask what they could do to help. It seemed as if our small faith act had sent a spark into a powder keg. People who had been silently suffering and quietly concerned suddenly saw our moral witness as a rallying cry. Everyone who called wanted to know when we would be going back to the General Assembly.

So we started to make plans to petition our legislators again the following Monday. We put the word out through our coalition partners and met with people who were willing to be arrested to tell them what we had learned the week prior and offer training in nonviolence. Having worked for years to plan lobby days at the legislature, I admit I was surprised to see that hundreds of people had showed up on Jones Street on only a few days’ notice. The second Monday, twice as many people were arrested, as hundreds packed into the statehouse rotunda, singing freedom songs and chanting, “This is what democracy looks like.” Our moral movement had touched a nerve. When the 32 arrestees were released the next morning, we announced that we would be back again the following week for another “Moral Monday.”

On that third Monday, when the number of volunteers willing to risk arrest doubled once again, our crowd packed both floors of the statehouse rotunda, spilling out into hallways and onto porches outside the building. As officers began to arrest our moral witnesses, hundreds moved outside the building, where they found the transport bus that had been sent over to deliver people to jail. At the sight of a sister or brother in handcuffs being led to the bus, the crowd would erupt with shouts of “Thank you!” and “We love you!” Our friends who were being processed out through the building’s basement cafeteria said they could hear the roar of the crowd before they even got outside.

Blinded by their own propaganda, the extremists simply couldn’t make sense of why thousands of North Carolinians were suddenly rising up in protest against their regime. Because our crowds had outgrown the building, we set up a stage on the mall behind the statehouse the next week, giving folks an hour or so after getting off work at five to gather, sing together, hear the stories of people who were directly affected by our state’s extremism and state clearly the reasons for our moral dissent. Legislators and their staff came out on the statehouse balconies to observe the open-air People’s Assembly that was happening outside their chambers. One Republican state senator, Tom Goolsby, wrote it off as a “Moron Monday” in his local paper back home, but such callous disregard only fueled the media frenzy around this popular uprising. When the time came for our moral witnesses to enter the statehouse, risking arrest, the crowd parted, creating an aisle down the middle. People lifted their hands to bless the scores of sisters and brothers who were laying down their freedom to proclaim to North Carolina that we were under attack.

The stage at the inaugural 2014 Moral Mondays protest in Raleigh, North Carolina. Photo by Ari Berman.

The media jumped at the scene of thousands of people gathered on the Halifax Mall, improvising a way of being together even as we reflected the multiethnic democracy that America strives to become. If it had happened just once, it would have been a high-water mark in our nation’s long march toward freedom. But the incredible thing — the fact that amazed me over and again — was that it kept happening. Word spread, and the crowd kept growing. I went out of state for a meeting at Highlander that had been planned for months, and while I was away, Moral Monday kept growing. Throughout one of the wettest summers on record in North Carolina, thousands of people stood outside their statehouse every Monday evening for 13 weeks and never got rained on. To the tune of the old spiritual “Wade in the Water,” one of our song leaders sang, “Forward together, not one step back / God gonna trouble the waters.”

It seemed as if a new kind of revival had taken hold of us, reminiscent of the camp meetings at which people gathered outdoors to hear the message of America’s Third Great Awakening in the late 19th century, when evangelical preachers made a direct connection between personal salvation and social justice. We improvised a liturgy that was deeply rooted in the lessons of our fusion coalition. Music mattered, so Yara Allen worked closely with the diverse cultural artists who were already committed to the movement to begin each gathering with songs that sang of our struggle. We reworked old freedom songs and improvised new chants on the spot. Watching the arrestees pour out of the building in handcuffs early on, someone shouted, “You’re gonna need another bus / ’cause baby there are more of us!” Moral Mondays weren’t a stage for artists to perform, but rather a platform from which they could lead us with their gifts. The point of the songs was to knit us together as a new kind of community.

After we joined our voices together in singing, we knew it was important for the crowd to hear from people directly affected by economic hardship and injustice. So this became our testimony time. An unemployed worker would stand up front and tell us what losing unemployment benefits meant to him and his family. A teacher would testify about what budget cuts meant for her and her classroom. A woman who qualified for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act told us what it feels like to know you can’t get treatment for cancer because some politicians in Raleigh are still mad that a black man is in the White House. Week after week, moral witnesses came forward to speak for themselves about how the legislators’ extremism was hurting North Carolina. We had learned that these poor and hurting people were the capstone of our moral arch. As it turned out, they were also some of our most compelling speakers. Many who came to a Moral Monday unsure of how they felt about political issues said these testimonies gave them clarity: they knew that laws which so obviously hurt people are wrong and must be challenged.

The platform our fusion coalition had built was one from which poor and hurting people’s voices could be heard. They were our featured speakers, and we invited them to share their stories regardless of race, creed or political affiliation. Of course, once the media frenzy took off, all of those politicians who spend millions of dollars to get their faces on TV couldn’t wait to get in front of the cameras. When we told them that our stage wasn’t for them, some of them started giving interviews to reporters on the edge of the crowd. I’ll never forget one evening, as a registered Republican and a registered Democrat were standing on stage together, talking about how the legislature had cut off their unemployment benefits, I noticed a state legislator giving an interview to the press. As soon as our two unemployed brothers had finished, I stepped to the microphone and asked the whole crowd to help me shame the politician into taking his show somewhere else. We were absolutely clear that anyone was welcome to be part of Moral Mondays, but we were gathered to hear from the people about how our state’s extremism was affecting them.

Because we knew that the opposition would fall back on so-called political realism (“You may not like it, but this is simply how it is”), we also knew it was important for the people to hear expert testimony that another way is possible. So, following the testimony of directly affected people each week, we created space in our liturgy for economists, public policy experts and lawyers to lay out our agenda and explain how it would work. College graduates who came to Moral Mondays said they learned more about government and civil society in those short talks than they had in whole semesters of mandatory civics classes. As the great American pragmatist John Dewey taught us, “learning by doing” is key to internalizing the principles we hold dear as a people. Moral Mondays became a space where a new North Carolina could practice democracy together. We were learning the principles of our state constitution by putting them into practice.

But perhaps the most distinctive mark of Moral Mondays — the focal point of our liturgy that gave the movement its name — was our insistence that, at its heart, our movement have a moral framework. Like the old revival services, each week concluded with a sermon and an altar call, when those who wished to make a new spiritual commitment were invited to come forward publicly. As a Christian preacher from a revivalist tradition, I knew this pattern well. But I was careful to acknowledge that my Holy Bible was not the only holy book. When I or another minister stood to preach, we never stood alone. We stood with Christian, Jewish and Muslim clerics surrounding us, offering the people a visible sign of the message we were trying to proclaim. Each of us had a tradition we held dear and a message we shared with our flocks on Friday, Saturday or Sunday. We weren’t giving any of that up. But on Monday we were learning to stand together and proclaim the deepest shared values of our faith traditions. We were learning how those values are embedded in our state constitution. And we were experiencing a revival like we’d never seen before — one where the Spirit lifts us all from where we were to higher ground.

I started to share a bit of insight I’d learned from my son, who studied environmental science in college. He told me, “Daddy, if you ever get lost in mountainous terrain, it’s important to know that there’s something called a snake line. Below the snake line, you might run into a copperhead or a rattlesnake sunning on the rocks of our Blue Ridge Mountains. But if you can get above the snake line, you’re safe, because those venomous creatures can’t live up there.” Moral Mondays were exposing the extremism of venomous politics in our state and helping folk see what dangerous terrain we had gotten ourselves into. But I kept telling them that there was a snake line somewhere on the mountain. If we could just move together toward higher ground, we’d be all right. The important thing was not to give up. The important thing was to keep on climbing. Every week I cried out against the nightmare we were witnessing to hold out the hope of higher ground.

This public proclamation was essential to our liturgy, but it was not the end. Every week when I was finished preaching, I invited people to come forward and make a public profession of their faith in a new North Carolina by exercising their constitutional right to petition their legislators in the General Assembly. They knew, of course, that they were risking arrest. Each person who had decided to make this public witness wore an armband to signify that they’d spent the afternoon doing nonviolence training at a local church. But it was an awe-inspiring sight, week after week, to watch the crowd part and make way for these nonviolent foot soldiers who were ready to sacrifice their own freedom to put our proposed future into practice. A Presbyterian minister from Charlotte, attending his first Moral Monday, said, “Never in my life have I seen the proclaimed Word put on flesh and move into such a direct action.” Some of us who’d been doing liturgy all of our lives began to realize its power in the public square.

After the General Assembly adjourned and went home, stubbornly refusing to hear our cries, we scheduled one final Moral Monday in Raleigh, moving our stage from behind the statehouse to Fayetteville Street, Raleigh’s Champs-Élysées, on the opposite side of the old state capitol. Nearly a thousand people had gone to jail in a dozen weeks of civil disobedience, marking the largest state-focused direct action campaign in US history. Their commitment had gained the attention of the nation, bringing reporters from national newspapers and cable news networks. The biggest political story in the country wasn’t what was happening inside any legislative chambers, but what was happening at these weekly people’s assemblies.

Before that rally, where some 20,000 people gathered to conclude our long summer of discontent in Raleigh, the question the media kept asking was “What difference has all of this protest made?” Their imagination was often so captive to the story they had been telling that they couldn’t understand the words we were saying when we told them Moral Mondays weren’t a new movement. These protests had not erupted spontaneously as some sort of natural reflex against extremism. They were the fruit of long-term organizing and hard-fought coalition building. We tried over and again to explain how North Carolina’s extremism was itself a strategic attack against the fusion coalition that had produced Moral Mondays. But the point was a difficult fit with the 24-hour news cycle. Every time we opened the floor for questions, they wanted to know what difference we were making.

I’d been at this long enough to know that the doubts that are spoken in public are the ones that weigh on the minds of the people — especially of those who had only recently joined our ranks. So I chose as my text for that 13th Moral Monday Psalm 118, a beautiful song of ancient Israel that had taught us how the poor and rejected were to be the capstone of our movement. I highlighted what that psalm goes on to say: “This is the lord’s doing; it is marvelous in our eyes. This is the day which the lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

Yes, we had seen an avalanche of extremism. Yes, we had a long way to go to undo the cynical attacks of the governing elites. But we could not press on without taking time to celebrate how far we had come. I told those twenty thousand people gathered on Fayetteville Street to take a moment to look around at one another. We were the multiracial democracy that scared the hell out of Southern politicians. Despite the best efforts of their Southern Strategy to divide and conquer us, we had come together.

For every face in that beautiful sea of God’s children, there was a story. I recognized members of the teachers union who had, in the early days of our coalition building, thought the HKonJ agenda too broad for all of their members to accept. But our struggle had taught us how the enemy of voting rights is the enemy of education. Now here we were, standing together. I noted the pink shirts of Planned Parenthood members and recalled my early conversations with their president, Janet Colm. I’d told her that with our broad coalition we could not endorse abortion, so she asked, “Can you support women’s rights and access to health care?’ Absolutely, I told her, but I also needed something from her. Could she give us white women to speak up for a black woman’s right to vote? She said she’d do it herself. We went on a national talk show together. When the host asked Janet about Planned Parenthood, she said, “I’m actually here today to talk about voting rights.” When she turned to me as a representative of the NAACP and asked about voting, I said, “I’m actually here today to talk about women’s rights and access to health care.” This fusion coalition had brought us together, confusing old dividing lines and making more than one interviewer stutter as they tried to figure out new categories to name what was happening. “This is the lord’s doing,” I told the crowd that day. “And it is marvelous in our eyes.”

Without a doubt, we still had some steep hills to climb before we crossed the snake line and brought a majority of our legislators with us to the higher ground of fusion politics, but I knew by the end of 2013 that we’d passed a tipping point. Our state-based movement had necessarily focused on state government through local grass roots organizing. From the beginning, we’d taken the long view, knowing we could not measure our success by any one election or struggle, but must measure it by our capacity to stay together and build strength. Now, through Moral Mondays, we had an opportunity to take this moral movement to the nation. Just as the Montgomery bus boycott had been about much more than public transportation in one Southern city, our struggle in North Carolina was about more than winning seats in the legislature. It was about exposing the conspiracy of the governing elite to maintain absolute power through divide-and-conquer strategies. And it was about overcoming the fears they’d played upon for decades to become what, at our best, we all hope and pray to be.

On that 13th Moral Monday — the last Monday in July — we announced that we would commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Justice by holding 13 simultaneous Take the Dream Home rallies across North Carolina. What we had done in Raleigh we would go back and do in every congressional district in the state. We would do it to make clear to our elected representatives that they could not run away from our movement by adjourning and going home. But we would also do it as a statement to the nation: we cannot fulfill Dr. King’s dream by building monuments and holding commemorations in Washington, DC. No, we must heed what he said and go home. Because the battle for the soul of America is being fought at the state level, and nothing short of a moral movement converging in every state capital will make possible the reconstruction we need to fulfill our nation’s promise.

Excerpted from The Third Reconstruction: How a Moral Movement Is Overcoming the Politics and Division of Fear by The Reverend Dr. William J. Barber II with Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove (Beacon Press, 2016). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.