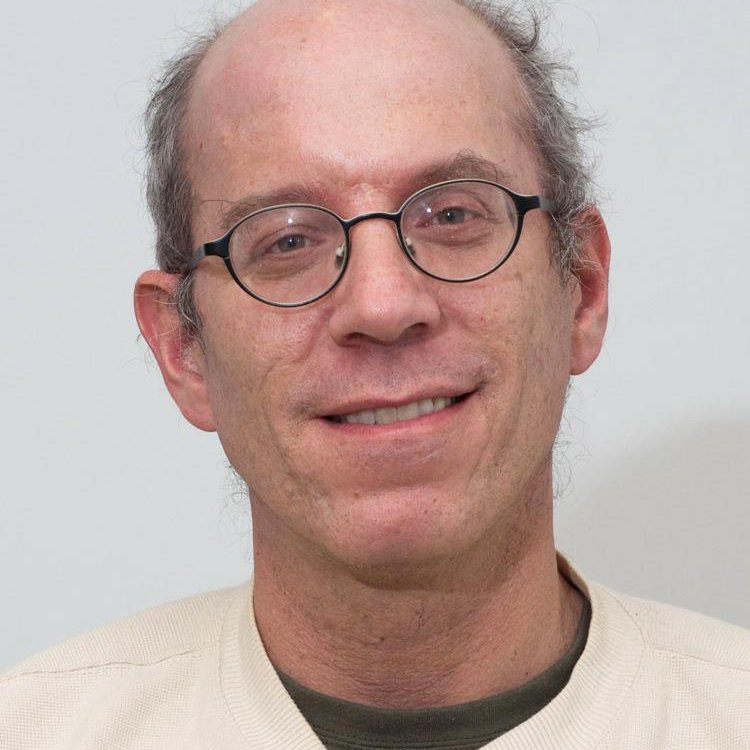

Women carry firewood on March 15, 2017 as they walk back to a makeshift camp on the outskirts of Baidoa, in the southwestern Bay region of Somalia, where thousands of internally displaced people arrive daily after they fleeing the parched countryside. The United Nations is warning of an unprecedented global crisis with famine already gripping parts of South Sudan and looming over Nigeria, Yemen and Somalia, threatening the lives of 20 million people. (Photo by Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at Foreign Policy in Focus.

One death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.

The quote comes from Stalin. The policy comes from Donald Trump.

Trump famously changed his policy on Syria after seeing photographs of a couple Syrian children killed by a chemical attack. It didn’t matter that the Syrian government had already killed thousands of children. In targeting the Assad regime, Trump was moved by the tragedy, not the statistic.

When it comes to world hunger, Trump’s resistance to statistics is even more appalling. There are now 1.4 million children at risk of dying from famine. No one apparently has shown Donald Trump, or his daughter Ivanka, any photos of these at-risk children. So, the US president is comfortably ignoring this statistic.

Because of a combination of weather conditions and military conflict — the two horsemen of the 21st century apocalypse — 20 million people are on the verge of starvation in four countries: Yemen, Somalia, South Sudan and Nigeria. It’s the worst humanitarian crisis since World War II, according to a senior UN official. In response, the UN put out a request for $4.4 billionin emergency assistance to avert catastrophe.

As of the middle of April, it hadn’t even received a billion.

At first glance, the United States comes out looking pretty good in terms of contributions. It tops the list of donors at $407 million (followed by various EU countries, Canada, Japan and even $60 million in private pledges).

It turns out, however, that all the money that Washington has contributed this year comes from an allocation made during the Obama administration. Last year, in fact, the United States provided 28 percent of the assistance to the four countries.

This year, USAID hasn’t added anything to meet the emergency famine relief appeal, which is no surprise. In Trump’s budget request, USAID stands to lose 37 percent of its funding. After all, Donald Trump has declared foreign assistance a zero-sum game: What doesn’t go to them can go to us. “America First” means that we protect our own first.

Except that Trump isn’t giving to the most needy at home. Our billionaire president is also threatening to take away the health care of millions of Americans. His proposed federal budget would dramatically reduce programs for the working poor like affordable housing.

The Trump doctrine, such that it is, is really all about taking from the poor and giving to the rich.

Trump’s America First approach, then, is a shortsighted, cruel and ultimately self-defeating shell game. Unless Donald Trump reverses his opposition to foreign aid, he will go down in history not just as the Absentee Golfer President or the Insane Clown President.

He’ll be forever known as the Hunger President.

Full-Spectrum Famine

Yemen has been in a precarious state for some time. It’s a desperately dry place where as many as 4,000 people a year were dying in disputes over land and water even before the outbreak of the current hostilities.

In 2014, a Shia religious-political movement known as the Houthis threw their lot in with ousted leader Ali Abdullah Saleh, a corrupt politician who’d ruled for three decades before losing his position during the Arab Spring protests that swept through Yemen in 2011. Together, they took over the capital and surged southward to expel the government of former military commander Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, who had holed up in the port city of Aden.

That’s when Saudi Arabia intervened on the side of Hadi and against the Houthis. The United States has been assisting the Saudis from the beginning by sending weapons and providing intelligence. The United States has also been helping to refuel bombers that have increasingly targeted civilian sites such as schools and hospitals.

It’s all part of a larger struggle in the region between the Saudis and their Sunni allies on one side and Iran and its Shia allies on the other, though Iran denies that it has much to do with the Houthi struggle. The Trump administration has only upped the ante by restoring the arms sales to Saudi Arabia suspended by the Obama administration and aligning itself even more closely to Riyadh’s war effort.

The war has pushed Yemen over the brink. The areas where the most fighting has taken place — Taiz and Hodeidah — are, not surprisingly, where the risk of famine is greatest. Both sides are to blame, says Mark Kaye of Save the Children in Yemen:

This crisis is happening because food and supplies can’t get into the country. Yemen was completely dependent on imports of food, medicine and fuel prior to this crisis. You have one party delaying and significantly preventing food from getting into the country, and another on the ground detaining aid workers or preventing aid and food from getting to areas they don’t want it to go to.

Of course, it doesn’t make much sense to send in food and water to people only to make them into better-fed casualties in the ongoing conflict. And the conflict shows no sign of abating, with the Houthis governing in the capital and the Saudi-backed supporters of Hadi only in tenuous control of areas in the south. The geographic and sectarian divisions that make the conflict more complicated than just Houthi vs. Hadi also make a peace deal that much more elusive.

Of the four countries at risk of famine, Yemen is the place where the United States has perhaps the greatest chance of making a difference. It can stop supporting the Saudi war effort. It can begin to scale back its own drone attacks in Yemen. It can support the UN peace process.

Even just stepping back from the conflict — something that Donald Trump seemed to favor during the campaign as a general approach to any conflict not involving the Islamic State — would deprive the ongoing war in Yemen of some of the oxygen that keeps it going.

Climate Change and Famine

The Pentagon long ago figured out that climate change was becoming a chief driver of conflict worldwide. If anyone can persuade Donald Trump that climate change is real, it’s not going to be environmentalists. It’s going to be people with a lot of medals on their chest, people who know better than anyone that you can’t bomb a famine to make it go away.

The generals could begin a climate-change discussion with Trump by talking about what’s currently going on in Africa. The three African countries on the famine alert — South Sudan, Somalia and Nigeria — are all dealing with endemic military conflict. They’ve all been vulnerable to famine in the past. And climate change has been pushing them ever closer to the edge.

Take the example of Somalia, which last experienced a famine in 2011. Somalis depend on agriculture and livestock. Even the most modest increase in temperature throws the ecosystem out of equilibrium.

“Awareness is growing among Somalis themselves about climate change: Communities across the country have noticed marked changes in temperature and rainfall, although most attribute it to divine retribution for the failings of humankind,” writes Halae Fuller in a Stimson Center brief from 2011. “African farmers and herders have adapted to changing environmental conditions with remarkable resilience. But where individual ingenuity fails, Somalia lacks the institutions and government structure needed to protect its population against increased food insecurity.”

A growing population and a shrinking resource base are a recipe for disaster under any circumstance. Throw in two dry spells in 2016, and now nearly half the Somali population needs emergency food relief.

The failure of the international community — and particularly the United States — to help those in desperate need in Somalia, South Sudan and Nigeria could become a powerful recruitment tool for anti-Western terrorist organizations. At the very least, the increased competition for limited resources will sharpen already-existing political and sectarian divisions.

The Trump administration could continue to avert its eyes from famine. It could continue to deny the real-world impact of climate change. And it could insist that drone attacks from above are the only way of dealing with terrorists on the ground. But it won’t be able to pretend for long that these problems won’t ultimately affect the United States. The growing number of refugees pouring out of those countries and the growing anger of those who perceive that they’ve been abandoned by the West will necessarily have a blowback effect on the last superpower standing.

On this narrower issue of famine relief, the Trump administration can still change its position. Right now, it’s living off the political capital and budget allocations of the Obama administration. That will run out very soon.

If humanitarianism fails to persuade Trump, perhaps naked geopolitics could do the trick.

Significantly, on that list of donors answering the UN famine appeal, one country is conspicuously absent: China. In the Trump era, China has been very vocal about its desire to be a more prominent player on the world stage. But here’s a reminder: It’s pay to play. If China wants to shoulder global responsibilities, it must start by paying attention to the world’s most vulnerable people.

In the meantime, while China considers the costs of global leadership, the United States still has a chance, by making a splashy and significant contribution to famine relief, to regain some portion of its status as a global leader in an arena that actually means something for the lives of millions of people.

If it doesn’t, Trump will have more than just a couple tragedies on his hands. He’ll face some very damning statistics indeed.